Stream processing systems

- 11 minutes

The frameworks that we have looked at so far (MapReduce, Spark, GraphLab) were primarily designed to perform batch computations. Their inputs are typically large distributed datasets, which are processed for several hours to yield a large, useful output. The use of these frameworks was originally restricted to data scientists and programmers, who used them for specific, large queries where this high latency was tolerable. However, as the use of big data gained prevalence within enterprises, there was a move toward ad hoc querying of data, with expected latencies of minutes, not hours. Tools like Pig, Hive, Shark, and Spark SQL allowed many businesses to ask complex questions of their data, without relying on a large pool of highly trained programmers. The cloud drove this adoption even further, providing an elastic supply of compute resources for the duration of an ad hoc query.

Soon, the expectation of latencies got even lower. Big data began to be received in real time, and was often only valuable for a short duration. For example, search engines required the best combination of advertisements to be served within milliseconds for each query; social media websites detected trends and trending topics and hashtags, and system monitoring tools detected complex patterns across several large infrastructure components. To be able to provide such low latencies, a new class of stream processing frameworks began to take shape. These had fundamentally different requirements and constraints from the batch and interactive processing systems of the past.

This led to the advent of stream processing systems.

Stream processing

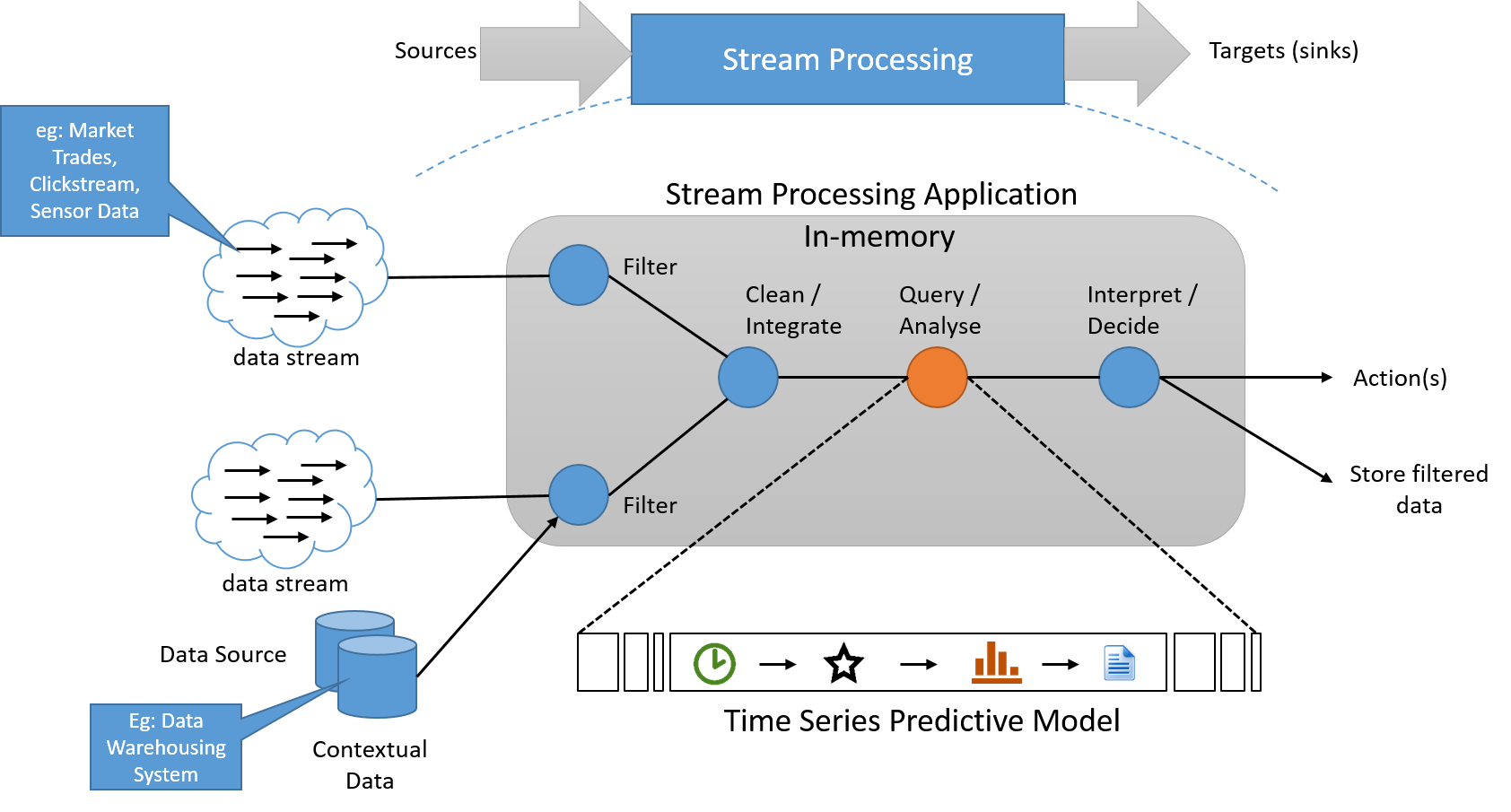

The stream processing paradigm applies a series of operations on each element of data emitted by an infinitely long input data source. The series of operations is generally pipelined, which adds dependencies between operations. Within the processing application, state information is often read from and written to a small, fast data source. The output of a pipeline of stream operations is also a data stream. This can be used to trigger other applications, or be buffered and stored to stable storage. The basic conceptual architecture of such a system is shown below.

Figure 6: A stream processing system must process data in-stream, with a separate pipeline for storage, if needed, which does not lie on the "critical path"

Eight rules for stream processing

Stonebraker et. al. described eight basic rules for stream processing systems.

Rule 1: Keep the data moving

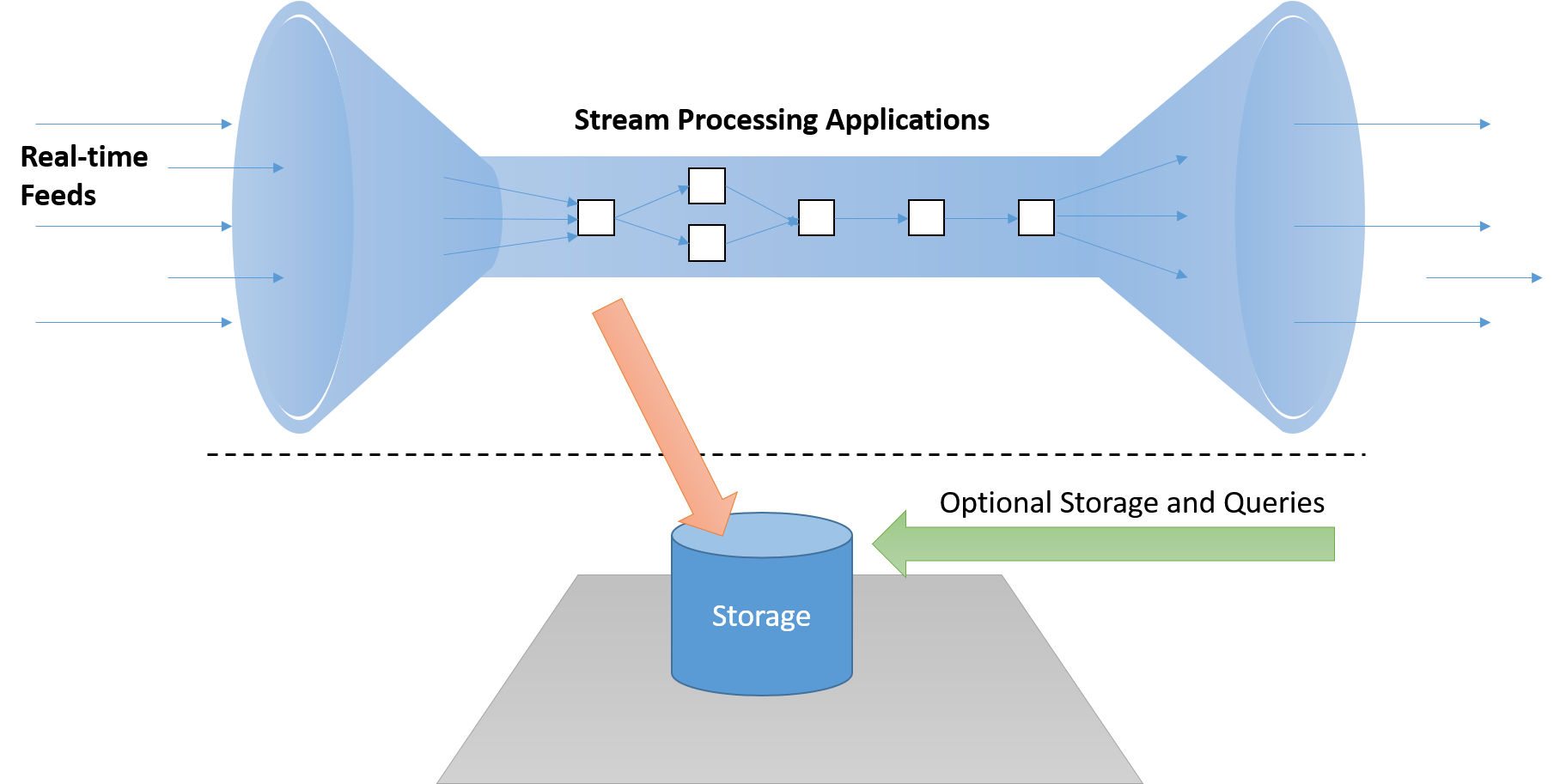

A real-time stream processing framework must be able to process messages "in-stream" without having to store them on disk, which adds unacceptable latency on the critical path. Additionally, these systems should be active (event driven) and not passive (whereby applications need to poll the results to detect conditions of interest).

Figure 7: A stream processing system must process data in-stream, with a separate pipeline for storage, if needed, which does not lie on the "critical path"

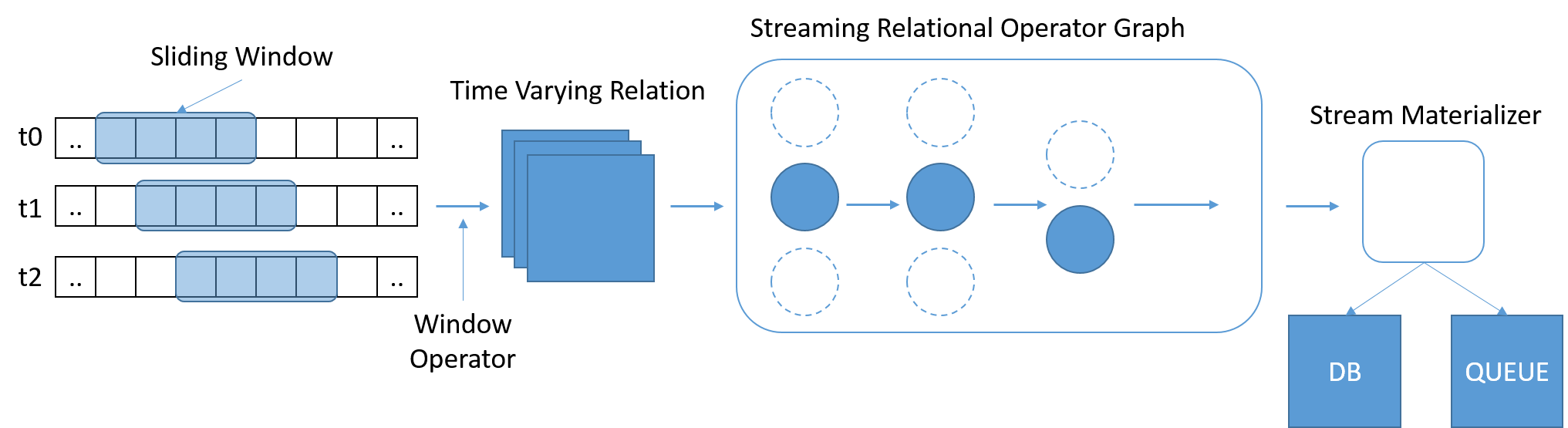

Rule 2: Streams should support querying using SQL

SQL has emerged as a widely used and familiar standard for querying data. However, traditional SQL operates on a fixed amount of data, whereby reaching the end of the table tells the query it is completed. In streaming scenarios, the data increases continuously. Stonebraker et. al. perceived the need for a StreamSQL language, with variable-length time-based sliding windows defining the scope of a query. Windows could be defined using time, number of messages, or any arbitrary parameters. Additional operators may be needed to merge messages from multiple streams.

Figure 8: StreamSQL should process subsets of the data, and allow relations to be expressed across windows

Rule 3: Handle stream imperfections

In real-time systems, data can be lost, arrive late, or arrive out of order. A stream processing system cannot wait indefinitely for data, but also may not have the flexibility to ignore or miss any data. Such systems must be resilient against stream imperfections, with mechanisms like configurable timeouts and "slack times," during which a late arrival can be accepted.

Rule 4: Generate predictable outcomes

The outcome of any stream processing system must be deterministic and repeatable by replaying the stream. This is particularly hard when the system is operating on multiple concurrent streams, or when messages arrive out of order. Messages must be produced in ascending time order, irrespective of their arrival time. This property also enables fault tolerance, by making it reasonable to replay streams upon which processing failed.

Rule 5: Integrate stored state

Stream processing applications must often combine the present with the past. For example, when recommending an ad to a user, a search engine must combine the current information about the search term and the current state of the ad market, with past information about the user's click habits. Integrating stored state and streaming data also allows seamless switching, whereby an algorithm can be tested on historical data, and then switched over to the live stream when it works satisfactorily. The data should be stored in the same system address space as the application, perhaps using an embedded database, to allow the use of a uniform language that deals with stored and streaming data.

Rule 6: Guarantee high availability

Stream processing systems work in real time, and often cannot tolerate restart recoveries. Such systems must allow a hot switchover to a backup or shadow, which must be regularly synchronized with the primary. The integrity of the data must be guaranteed, in accordance with rule 4.

Rule 7: Support partitioning and auto-scaling

Distributed processing is the standard model of operation for all such large systems. A good stream processing architecture should be non-blocking and exploit modern multi-threaded architectures. Further, it should be able to handle the scaling out or in of the system on its own, by adding or removing machines, either based on increased or decreased data volumes or based on processing delays or complexities. Additionally, it must automatically and transparently perform load balancing over the available machines. The end user should not have to deal with any of this complexity.

Rule 8: Make sure it can keep up

All system components should be designed for high performance, with a minimal number of operations happening out of core. The system must be tested and benchmarked based on the target workload, and the throughput and latency goals must be validated.

Evolution of stream processing engines

Aurora (2002) was one of the earliest stream processing systems, also developed by Stonebraker et al. at MIT and Brown University. Aurora treated the stream processing problem as a directed acyclic graph (DAG).

The stream input is a sequence of unbounded tuples (a1, a2, ..., an) over time that flow from upstream (start) to downstream (output). An entire application can be built by adding different combinations of processing boxes and drawing links between them. Aurora was a single-node system, which lacked many of the scalability requirements of a stream processing engine. A new version of Aurora named Aurora* (2003) was created to combine many Aurora nodes over a network. Thus, scalability was achieved by partitioning the different stages of the stream processing job over different physical nodes. Finally, the Medusa project (2003) added federation support to Aurora, allowing collaboration and sharing by multiple users.

Borealis (2005) was the next extension of the Aurora project, which added support for high availability using active replication. The replicas were carefully synchronized to provide data consistency.

Apache Storm (2011) was a stream processing engine developed by X. Here, the processing nodes (Bolts) could subscribe to streams from different sources (Spouts), thereby enabling a simple subscriber model of computation. Storm provides guaranteed message processing, regardless of node failures, and enables exactly-once semantics to ensure that data is neither undercounted nor overcounted. Apache S4 (2011) was a similar subscription system developed at Yahoo!. It is symmetrical, in the sense that all nodes are equal and there is no centralized control, in the hopes of making it scalable. S4 did not support dynamically adding or removing nodes to and from a running cluster. Apache Samza (2013) is another multi-subscriber system in this mold that we will explore in more detail.

Storm, Samza, and S4 follow the traditional streaming model, known as record-at-a-time processing. In this model, stateful operators process arriving records, using the new data to modify internal state and then emit new records. Fault tolerance and recovery are done by replication, either by making multiple copies of processing elements or by buffering and storing backups of messages upstream, and resending them downstream, in case of failures. Also, as the layout of the DAG grows more complex, it is hard to ensure consistency across different paths. Finally, combining these frameworks with batch systems is non-trivial, and is often done using the Lambda architecture (discussed later).

Another approach to designing stream-processing systems is provided by Spark Streaming (2012), which provides "micro-batching." Micro-batching converts stream computations into a set of extremely fast computations, with latencies from hundreds of milliseconds to a few seconds. At the cost of increased latency, this makes it easier to provide fault tolerance and exactly-once semantics on the result of each micro-batch.

Selecting the correct framework to use for a task is a factor of the expected latency, fault tolerance, and message delivery guarantees, as well as the skillset of the users and desired development costs. In the next unit, we will explore the internals of these frameworks in more detail, by studying Apache Samza.