Microsoft Power Fx overview

Power Fx is the low-code language that will be used across Microsoft Power Platform. It's a general-purpose, strong-typed, declarative, and functional programming language.

Power Fx is expressed in human-friendly text. It's a low-code language that makers can work with directly in an Excel-like formula bar or Visual Studio Code text window. The "low" in low-code is due to the concise and simple nature of the language, making common programming tasks easy for both makers and developers. It enables the full spectrum of development from no-code for those who have never programmed before to "pro-code" for the seasoned professional, with no learning or rewriting cliffs in between, enabling diverse teams to collaborate and save time and expense.

Note

- Microsoft Power Fx is the new name for the formula language for canvas apps in Power Apps. This overview and associated articles are a work in progress as we extract the language from canvas apps, integrate it with other Microsoft Power Platform products, and make it available as open source. To learn more about and experience the language today, start with Get started with formulas in canvas apps in the Power Apps documentation and sign up for a free Power Apps trial.

- In this article, we refer to makers when we describe a feature that might be used at either end of the programming skill spectrum. We refer to the user as a developer if the feature is more advanced and is likely beyond the scope of a typical Excel user.

Power Fx binds objects together with declarative spreadsheet-like formulas. For example, think of the Visible property of a UI control as a cell in an Excel worksheet, with an associated formula that calculates its value based on the properties of other controls. The formula logic recalculates the value automatically, similar to how a spreadsheet does, which affects the visibility of the control.

Also, Power Fx offers imperative logic when needed. Worksheets don't typically have buttons that can submit changes to a database, but apps often do. The same expression language is used for both declarative and imperative logic.

Power Fx will be made available as open-source software. It's currently integrated into canvas apps, and we're in the process of extracting it from Power Apps for use in other Microsoft Power Platform products and as open source. More information: Microsoft Power Fx on GitHub

This article is an overview of the language and its design principles. To learn more about Power Fx, see the following articles:

- Data types

- Operators and identifiers

- Tables

- Variables

- Imperative logic

- Global support

- Expression grammar

- YAML formula grammar

Think spreadsheet

What if you could build an app as easily as you build a worksheet in Excel?

What if you could take advantage of your existing spreadsheet knowledge?

These were the questions that inspired the creation of Power Apps and Power Fx. Hundreds of millions of people create worksheets with Excel every day; let's bring them app creation that's easy and uses Excel concepts that they already know. By breaking Power Fx out of Power Apps, we're going to answer these questions for building automation, or a virtual agent, or other domains.

All programming languages, including Power Fx, have expressions: a way to represent a calculation over numbers, strings, or other data types. For example, mass * acceleration in most languages expresses multiplication of mass and acceleration. The result of an expression can be placed in a variable, used as an argument to a procedure, or nested in a bigger expression.

Power Fx takes this a step further. An expression by itself says nothing about what it's calculating. It's up to the maker to place it in a variable or pass it to a function. In Power Fx, instead of only writing an expression that has no specific meaning, you write a formula that binds the expression to an identifier. You write force = mass * acceleration as a formula for calculating force. As mass or acceleration changes, force is automatically updated to a new value. The expression described a calculation, a formula gave that calculation a name and used it as a recipe. This is why we refer to Power Fx as a formula language.

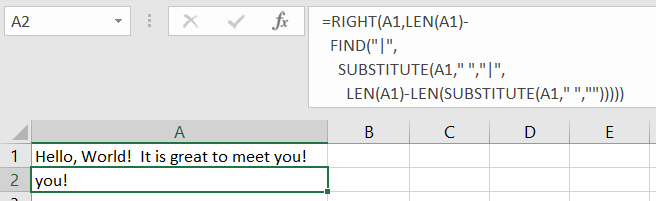

For example, this formula from Stack Overflow searches a string in reverse order. In Excel, it looks like the following image.

Screenshot of a formula bar in Excel with the formula: =RIGHT(A1,LEN(A1)- FIND("|", SUBSTITUTE(A1," ","|", LEN(A1)-LEN(SUBSTITUTE(A1," ","")))) Cell A1 contains the text "Hello, World! It is great to meet you!" Cell A2 contains the text "you!"

Power Fx works with this same formula, with the cell references replaced with control property references:

Screenshot of a Power Fx formula bar in Power Apps. The formula is =RIGHT(Input.Text,Len(Input.Text)- FIND("|", SUBSTITUTE(Input.Text," ","|", Len(Input.Text)-Len(Substitute(Input.Text," ","")))) In the Input box below the formula, the text "Hello, World! It is great to meet you!" appears, letter by letter. At the same time in the Label box, the letters of the last word appear. When the full text appears in the Input box, the word "you!" appears in the Label box.

As the Input control value is changed, the Label control automatically recalculates the formula and shows the new value. There are no OnChange event handlers here, as would be common in other languages.

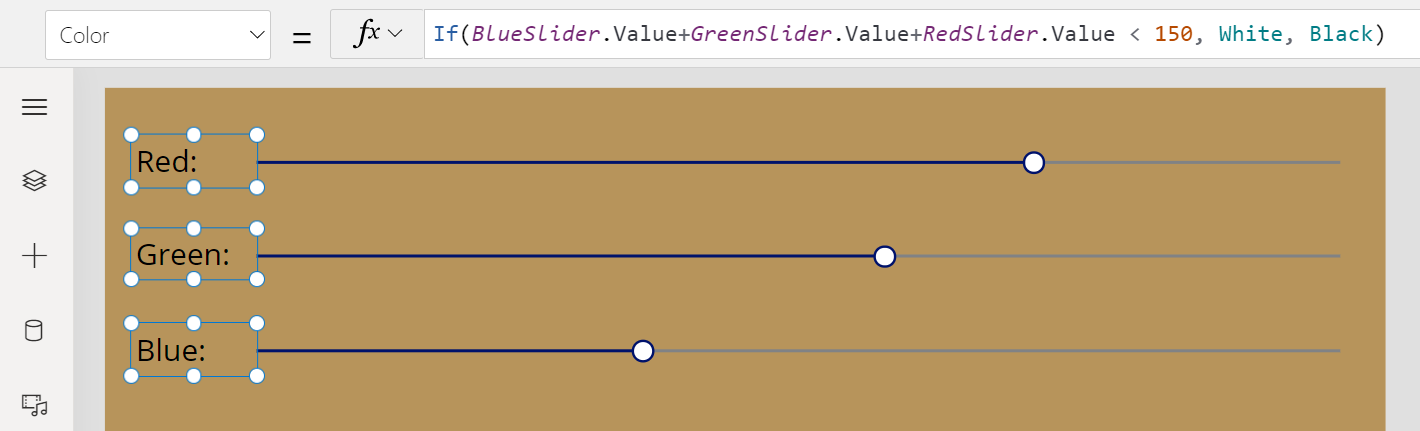

Another example that uses a formula for the Fill color of the screen. As the sliders that control Red, Green, and Blue are changed, the background color automatically changes as it's being recalculated.

There are no OnChange events for the slider controls, as would be common in other languages. There's no way to explicitly set the Fill property value at all. If the color isn't working as expected, you need to look at this one formula to understand why it isn't working. You don't need to search through the app to find a piece of code that sets the property at an unexpected time; there is no time element. The correct formula values are always maintained.

As the sliders are set to a dark color, the labels for Red, Green, and Blue change to white to compensate. This is done through a simple formula on the Color property for each label control.

What's great about this is that it's isolated from what's happening for the Fill color: these are two entirely different calculations. Instead of large monolithic procedures, Power Fx logic is typically made up of lots of smaller formulas that are independent. This makes them easier to understand and enables enhancements without disturbing existing logic.

Power Fx is a declarative language, just as Excel is. The maker defines what behavior they want, but it's up to the system to determine and optimize how and when to accomplish it. To make that practical, most work is done through pure functions without side effects, making Power Fx also a functional language (again, just as Excel is).

Always live

A defining aspect of worksheets is that they're always live, and changes are reflected instantaneously. There is no compile or run mode in a worksheet. When a formula is modified or a value is entered, the worksheet is immediately recalculated to reflect the changes. Any errors that are detected are surfaced immediately, and don't interfere with the rest of the worksheet.

The same thing is implemented with Power Fx. An incremental compiler is used to continuously keep the program in sync with the data it's operating on. Changes are automatically propagated through the program's graph, affecting the results of dependent calculations, which might drive properties on controls such as color or position. The incremental compiler also provides a rich formula editing experience with IntelliSense, suggestions, autocomplete, and type checking.

In the animation below, the order number is displayed in a label control dependent on the slider control, even though there are two errors on the labels below it. The app is very much alive and interactive. The first attempt at fixing the formula by entering .InvalidName results in an immediate red line and error displayed, as it should, but the app keeps running.

When .Employee is entered, this causes the Data pane to add the Employees table, metadata for this table is retrieved, and suggestions for columns are immediately offered. We just walked across a relationship from one table to another, and the system made the needed adjustments to the app's references. The same thing happens when adding a .Customer.

After each change, the slider continues with its last value and any variables retain their value. Throughout, the order number has continued to be displayed in the top label as it should. The app has been live, processing real data, the entire time. We can save it, walk away, and others can open and use it just like Excel. There is no build step, no compile, there's only a publish step to determine which version of the app is ready for users.

Low code

Power Fx describes business logic in concise, yet powerful, formulas. Most logic can be reduced to a single line, with plenty of expressiveness and control for more complex needs. The goal is to keep to a minimum the number of concepts a maker needs to understand—ideally, no more than an Excel user would already know.

For example, to look up the first name of an employee for an order, you write the Power Fx as shown in the following animation. Beyond Excel concepts, the only added concept used here is the dot "." notation for drilling into a data structure, in this case .Employee.'First Name'. The animation shows the mapping between the parts of the Power Fx formula and the concepts that need to be explicitly coded in the equivalent JavaScript.

Let's look more in-depth at all the things that Power Fx is doing for us and the freedom it has to optimize because the formula was declarative:

Asynchronous: All data operations in Power Fx are asynchronous. The maker doesn't need to specify this, nor does the maker need to synchronize operations after the call is over. The maker doesn't need to be aware of this concept at all, they don't need to know what a promise or lambda function is.

Local and remote: Power Fx uses the same syntax and functions for data that's local in-memory and remote in a database or service. The user need not think about this distinction. Power Fx automatically delegates what it can to the server, to process filters and sorts there more efficiently.

Relational data: Orders and Customers are two different tables, with a many-to-one relationship. The OData query requires an "$expand" with knowledge of the foreign key, similar to a Join in SQL. The formula has none of this; in fact, database keys are another concept the maker doesn't need to know about. The maker can use simple dot notation to access the entire graph of relationships from a record.

Projection: When writing a query, many developers write

select * from table, which brings back all the columns of data. Power Fx analyzes all the columns that are used through the entire app, even across formula dependencies. Projection is automatically optimized and, again, a maker doesn't need to know what "projection" means.Retrieve only what is needed: In this example, the

LookUpfunction implies that only one record should be retrieved and that's all that's returned. If more records are requested by using theFilterfunction—for which thousands of records might qualify—only a single page of data is returned at a time, on the order of 100 records per page. The user must gesture through a gallery or data table to see more data, and it will automatically be brought in for them. The maker can reason about large sets of data without needing to think about limiting data requests to manageable chunks.Runs only when needed: We defined a formula for the

Textproperty of the label control. As the variable selected changes, theLookUpis automatically recalculated and the label is updated. The maker didn't need to write an OnChange handler for Selection, and didn't need to remember that this label is dependent upon it. This is declarative programming, as discussed earlier: the maker specified what they wanted to have in the label, not how or when it should be fetched. If this label isn't visible because it's on a screen that isn't visible, or itsVisibleproperty is false, we can defer this calculation until the label is visible and effectively eliminate it if that rarely happens.Excel syntax translation: Excel is used by many users, most of whom know that the ampersand (&) is used for string concatenation. JavaScript uses a plus sign (+), and other languages use a dot (.).

Display names and localization:

First Nameis used in the Power Fx formula whilenwind_firstnameis used in the JavaScript equivalent. In Microsoft Dataverse and SharePoint, there's a display name for columns and tables in addition to a unique logical name. The display names are often much more user-friendly, as in this case, but they have another important quality in that they can be localized. If you have a multilingual team, each team member can see table and field names in their own language. In all use cases, Power Fx makes sure that the correct logical name is sent to the database automatically.

No code

You don't have to read and write Power Fx to start expressing logic. There are lots of customizations and logic that can be expressed through simple switches and UI builders. These no-code tools have been built to read and write Power Fx to ensure that there's plenty of headroom for someone to take it further, while acknowledging that no-code tools will never offer all the expressiveness of the full language. Even when used with no-code builders, the formula bar is front and center in Power Apps to educate the maker about what's being done on their behalf so they can begin to learn Power Fx.

Let's take a look at some examples. In Power Apps, the property panel provides no-code switches and knobs for the properties of the controls. In practice, most property values are static. You can use the color builder to change the background color of the Gallery. Notice that the formula bar reflects this change, updating the formula to a different RGBA call. At any time, you can go to the formula bar and take this a step further—in this example, by using ColorFade to adjust the color. The color property still appears in the properties panel, but an fx icon appears on hover and you're directed to the formula bar. This fully works in two ways: removing the ColorFade call returns the color to something the property panel can understand, and you can use it again to set a color.

Here's a more complicated example. The gallery shows a list of employees from Dataverse. Dataverse provides views over table data. We can select one of these views and the formula is changed to use the Filter function with this view name. The two drop-down menus can be used to dial in the correct table and view without touching the formula bar. But let's say you want to go further and add a sort. We can do that in the formula bar, and the property panel again shows an fx icon and directs modifications to the formula bar. And again, if we simplify the formula to something the property panel can read and write, it again can be used.

These have been simple examples. We believe Power Fx makes a great language for describing no-code interactions. It is concise, powerful, and easy to parse, and provides the headroom that is so often needed with "no cliffs" up to low-code.

Pro code

Low-code makers sometimes build things that require the help of an expert or are taken over by a professional developer to maintain and enhance. Professionals also appreciate that low-code development can be easier, faster, and less costly than building a professional tool. Not every situation requires the full power of Visual Studio.

Professionals want to use professional tools to be most productive. Power Fx formulas can be stored in YAML source files, which are easy to edit with Visual Studio Code, Visual Studio, or any other text editor and enable Power Fx to be put under source control with GitHub, Azure DevOps, or any other source code control system.

Power Fx supports formula-based components for sharing and reuse. We announced support for parameters to component properties, enabling the creation of pure user-defined functions with more enhancements on the way.

Also, Power Fx is great at stitching together components and services built by professionals. Out-of-the-box connectors provide access to hundreds of data sources and web services, custom connectors enable Power Fx to talk to any REST web service, and code components enable Power Fx to interact with fully custom JavaScript on the screen and page.

Design principles

Simple

Power Fx is designed to target the maker audience, whose members haven't been trained as developers. Wherever possible, we use the knowledge that this audience would already know or can pick up quickly. The number of concepts required to be successful is kept to a minimum.

Being simple is also good for developers. For the developer audience, we aim to be a low-code language that cuts down the time required to build a solution.

Excel consistency

Microsoft Power Fx language borrows heavily from the Excel formula language. We seek to take advantage of Excel knowledge and experience from the many makers who also use Excel. Types, operators, and function semantics are as close to Excel as possible.

If Excel doesn't have an answer, we next look to SQL. After Excel, SQL is the next most commonly used declarative language and can provide guidance on data operations and strong typing that Excel doesn't.

Declarative

The maker describes what they want their logic to do, not exactly how or when to do it. This allows the compiler to optimize by performing operations in parallel, deferring work until needed, and pre-fetching and reusing cached data.

For example, in an Excel worksheet, the author defines the relationships among cells but Excel decides when and in what order formulas are evaluated. Similarly, formulas in an app can be thought of as "recalc-ing" as needed based on user actions, database changes, or timer events.

Functional

We favor pure functions that don't have side effects. This results in logic that's easier to understand and gives the compiler the most freedom to optimize.

Unlike Excel, apps by their nature do mutate state—for example, apps have buttons that save changes to the record in a database. Some functions, therefore, do have side effects, although we limit this as much as is practical.

Composition

Where possible, the functionality that's added composes well with existing functionality. Powerful functions can be decomposed into smaller parts that can be more easily used independently.

For example, a Gallery control doesn't have separate Sort and Filter properties. Instead, the Sort and Filter functions are composed together into a single Items property. The UI for expressing Sort and Filter behavior is layered on top of the Items property by using a two-way editor for this property.

Strongly typed

The types of all the values are known at compile time. This allows for the early detection of errors and rich suggestions while authoring.

Polymorphic types are supported, but before they can be used, their type must be pinned to a static type and that type must be known at compile time. The IsType and AsType functions are provided for testing and casting types.

Type inference

Types are derived from their use without being declared. For example, setting a variable to a number results in the variable's type being established as a number.

Conflicting type usage results in a compile-time error.

Locale-sensitive decimal separators

Some regions of the world use a dot (.) as the decimal separator, while others use a comma (,). This is what Excel does, too. This is commonly not done in other programming languages, which generally use a canonical dot (.) as the decimal separator for all users worldwide. To be as approachable as possible for makers at all levels, it's important that 3,14 is a decimal number for a person in France who has used that syntax all their lives.

The choice of decimal separator has a cascading impact on the list separator, used for function call arguments, and the chaining operator.

| Author's language decimal separator | Power Fx decimal separator | Power Fx list separator | Power Fx chaining operator |

|---|---|---|---|

| . (dot) | . (dot) | , (comma) | ; (semicolon) |

| , (comma) | , (comma) | ; (semicolon) | ;; (double semicolon) |

More information: Global support

Not object-oriented

Excel isn't object-oriented, and neither is Power Fx. For example, in some languages, the length of a string is expressed as a property of the string, such as "Hello World".length in JavaScript. Excel and Power Fx instead express this in terms of a function, as Len( "Hello World" ).

Components with properties and methods are object-oriented and Power Fx easily works with them. But where possible, we prefer a functional approach.

Extensible

Makers can create their components and functions by using Power Fx itself. Developers can create their components and functions by writing JavaScript.

Developer friendly

Although makers are our primary target, we try to be developer-friendly wherever possible. If it doesn't conflict with the design principles described previously, we do things in a way that a developer will appreciate. For example, Excel has no capability for adding comments, so we use C-like line and inline comments.

Language evolution

Evolving programming languages is both necessary and tricky. Everyone—rightfully—is concerned that a change, no matter how well-intentioned, might break existing code and require users to learn a new pattern. Power Fx takes backward compatibility seriously, but we also strongly believe that we won't always get it right the first time and we'll collectively learn what's best as a community. We must evolve, and Power Fx designed support for language evolution from the very beginning.

A language version stamp is included with every Power Fx document that's saved. If we want to make an incompatible change, we'll write what we call a "back compat converter" that rewrites the formula automatically the next time it's edited. If the change is something major that we need to educate the user about, we'll also display a message with a link to the docs. Using this facility, we can still load apps that were built with the preview versions of Power Apps from many years ago, despite all the changes that have occurred since then.

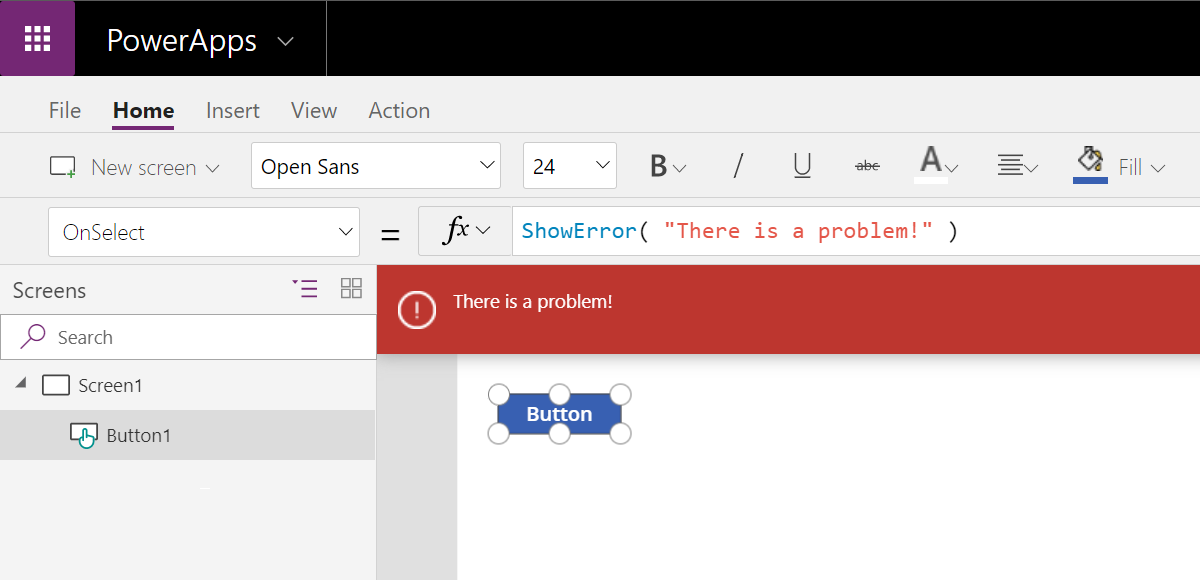

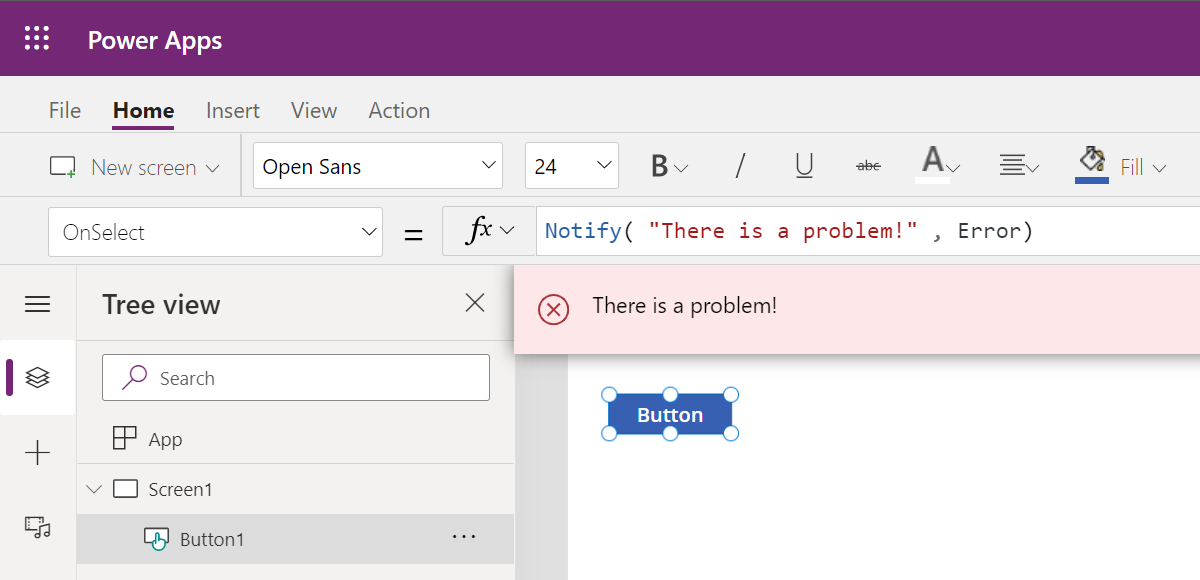

For example, we introduced the ShowError function to display an error banner with a red background.

Users loved it, but they also asked us for a way to show a success banner (green background) or an informational banner (blue background). So, we came up with a more generic Notify function that takes a second argument for the kind of notification. We could have just added Notify and kept ShowError the way it was, but instead we replaced ShowError with Notify. We removed a function that had previously been in production and replaced it with something else. Because there would have been two ways to do the same thing, this would have caused confusion—especially for new users—and, most importantly it would have added complexity. Nobody complained, everybody appreciated the change and then moved on to their next Notify feature.

This is how the same app looks when loaded into the latest version of Power Apps. No action was required by the user to make this transformation happen, it occurred automatically when the app was opened.

With this facility, Power Fx can evolve faster and more aggressively than most programming languages.

No undefined value

Some languages, such as JavaScript, use the concept of an undefined value for uninitialized variables or missing properties. For simplicity's sake, we've avoided this concept. Instances that would be undefined in other languages are treated as either an error or a blank value. For example, all uninitialized variables start with a blank value. All data types can take on the value of blank.

Related articles

Data types

Operators and identifiers

Tables

Variables

Imperative logic

Global support

Expression grammar

YAML formula grammar

Formulas in canvas apps