Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

Azure Service Bus sessions allow joint and ordered processing of unbounded sequences of related messages. Sessions can be used in first in, first out (FIFO) and request-response patterns. This article shows how to use sessions to implement these patterns when using Service Bus.

Note

The basic tier of Service Bus doesn't support sessions. The standard and premium tiers support sessions. For differences between these tiers, see Service Bus pricing.

First-in, first out (FIFO) pattern

To achieve FIFO processing in processing messages from Service Bus queues or subscriptions, use sessions. Service Bus isn't prescriptive about the nature of the relationship between messages, and also doesn't define a particular model for determining where a message sequence starts or ends.

A sender can initiate a session when submitting messages into a topic or queue by setting the session ID property to unique identifier defined by the application. At the AMQP 1.0 protocol level, this value maps to the group-id property.

On session-aware queues or subscriptions, sessions come into existence when there's at least one message with the session ID. Once a session exists, there's no defined time or API for when the session expires or disappears. Theoretically, a message can be received for a session today, the next message in a year's time, and if the session ID matches, the session is the same from the Service Bus perspective.

Typically, however, an application defines where a set of related messages starts and ends. Service Bus doesn't impose any specific rules. For instance, your application could set the Label property for the first message as start, for intermediate messages as content, and for the last message to end. The relative position of the content messages can be computed as the current message SequenceNumber delta from the start message SequenceNumber.

Important

When sessions are enabled on a queue or a subscription, the client applications can no longer send/receive regular messages. Clients must send messages as part of a session by setting the session ID and received by accepting the session. Clients might still peek a queue or subscription that has sessions enabled. See Message browsing.

The APIs for sessions exist on queue and subscription clients. There are two ways to receive sessions and messages: the imperative model, where you manually control when and how messages are received, and the handler-based model, which simplifies things by automatically managing the message loop and processing.

For samples, use links in the Samples section.

Session features

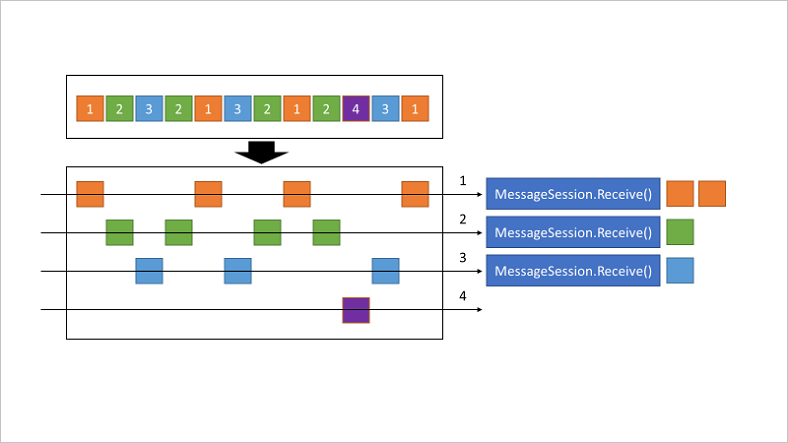

Sessions provide concurrent demultiplexing of interleaved message streams while preserving and guaranteeing ordered delivery.

A client creates a session receiver to accept a session. When the client accepts and holds a session, the client holds an exclusive lock on all messages with that session's session ID in the queue or subscription. It holds exclusive locks on all messages with the session ID that arrive later.

The lock is released when you call close methods on the receiver or when the lock expires. There are methods on the receiver to renew the locks as well. Instead, you can use the automatic lock renewal feature where you can specify the time duration for which you want to keep getting the lock renewed. The session lock should be treated like an exclusive lock on a file, meaning that the application should close the session as soon as it no longer needs it and/or doesn't expect any further messages.

When multiple concurrent receivers pull from the queue, the messages belonging to a particular session are dispatched to the specific receiver that currently holds the lock for that session. With that operation, an interleaved message stream in one queue or subscription is cleanly demultiplexed to different receivers and those receivers can also live on different client machines, since the lock management happens service-side, inside Service Bus.

The previous illustration shows three concurrent session receivers. One Session with SessionId = 4 has no active, owning client, which means that no messages are delivered from this specific session. A session acts in many ways like a sub queue.

The session lock held by the session receiver is an umbrella for the message locks used by the peek-lock settlement mode. Only one receiver can have a lock on a session. A receiver might have many in-flight messages, but the messages are received in order. Abandoning a message causes the same message to be served again with the next receive operation.

Message session state

When workflows are processed in high-scale, high-availability cloud systems, the workflow handler associated with a particular session must be able to recover from unexpected failures and can resume partially completed work on a different process or machine from where the work began.

The session state facility enables an application-defined annotation of a message session inside the broker, so that the recorded processing state relative to that session becomes instantly available when the session is acquired by a new processor.

From the Service Bus perspective, the message session state is an opaque binary object that can hold data of the size of one message, which is 256 KB for Service Bus Standard, and 100 MB for Service Bus Premium. The processing state relative to a session can be held inside the session state, or the session state can point to some storage location or database record that holds such information.

The methods for managing session state, SetState, and GetState, can be found on the session receiver object. A session that had previously no session state returns a null reference for GetState. The previously set session state can be cleared by passing null to the SetState method on the receiver.

Session state remains as long as it isn't cleared up (returning null), even if all messages in a session are consumed.

The session state held in a queue or in a subscription counts towards that entity's storage quota. When the application is finished with a session, it's therefore recommended for the application to clean up its retained state to avoid external management cost.

Impact of delivery count

The definition of delivery count per message in the context of sessions varies slightly from the definition in the absence of sessions. Here's a table summarizing when the delivery count is incremented.

| Scenario | Is the message's delivery count incremented |

|---|---|

| Session is accepted, but the session lock expires (due to time-out) | Yes |

| Session is accepted, the messages within the session aren't completed (even if they're locked), and the session is closed | No |

| Session is accepted, messages are completed, and then the session is explicitly closed | N/A (It's the standard flow. Here, messages are removed from the session) |

Request-response pattern

The request-reply pattern is a well-established integration pattern that enables the sender application to send a request and provides a way for the receiver to correctly send a response back to the sender application. This pattern typically needs a short-lived queue or topic for the application to send responses to. In this scenario, sessions provide a simple alternative solution with comparable semantics.

Multiple applications can send their requests to a single request queue, with a specific header parameter set to uniquely identify the sender application. The receiver application can process the requests coming in the queue and send replies on the session enabled queue, setting the session ID to the unique identifier the sender had sent on the request message. The application that sent the request can then receive messages on the specific session ID and correctly process the replies.

Note

The application that sends the initial requests should know about the session ID and use it to accept the session so that the session on which it's expecting the response is locked. It's a good idea to use a GUID that uniquely identifies the instance of the application as a session ID. There should be no session handler or a time out specified on the session receiver for the queue to ensure that responses are available to be locked and processed by specific receivers.

Sequencing vs. sessions

Sequence number on its own guarantees the queuing order and the extraction order of messages, but not the processing order, which requires sessions.

Say, there are three messages in the queue and two consumers.

- Consumer 1 picks up message 1.

- Consumer 2 picks up message 2.

- Consumer 2 finishes processing message 2 and picks up message 3, while Consumer 1 isn't done with processing message 1 yet.

- Consumer 2 finishes processing message 3, but consumer 1 is still not done with processing message 1 yet.

- Finally, consumer 1 completes processing message 1.

So, the messages are processed in this order: message 2, message 3, and message 1. If you need message 1, 2, and 3 to be processed in order, you need to use sessions.

If messages just need to be retrieved in order, you don't need to use sessions. If messages need to be processed in order, use sessions. The same session ID should be set on messages that belong together, which could be message 1, 4, and 8 in a set, and 2, 3, and 6 in another set.

Message expiration

For session-enabled queues or topics' subscriptions, messages are locked at the session level. If the time-to-live (TTL) for any of the messages expires, all messages related to that session are either dropped or dead-lettered based on the dead-lettering enabled on messaging expiration setting on the entity. In other words, if there's a single message in the session that has passed the TTL, all the messages in the session are expired. The messages expire only if there's an active listener. For more information, see Message expiration.

Samples

You can enable message sessions while creating a queue using Azure portal, PowerShell, CLI, Resource Manager template, .NET, Java, Python, and JavaScript. For more information, see Enable message sessions.

Try the samples in the language of your choice to explore Azure Service Bus features.

- .NET

- Java

- Python

- JavaScript