Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

In the Model-View-ViewModel (MVVM) architecture, data bindings are defined between properties in the ViewModel, which is generally a class that derives from INotifyPropertyChanged, and properties in the View, which is generally the XAML file. Sometimes an application has needs that go beyond these property bindings by requiring the user to initiate commands that affect something in the ViewModel. These commands are generally signaled by button clicks or finger taps, and traditionally they are processed in the code-behind file in a handler for the Clicked event of the Button or the Tapped event of a TapGestureRecognizer.

The commanding interface provides an alternative approach to implementing commands that is much better suited to the MVVM architecture. The ViewModel itself can contain commands, which are methods that are executed in reaction to a specific activity in the View such as a Button click. Data bindings are defined between these commands and the Button.

To allow a data binding between a Button and a ViewModel, the Button defines two properties:

Commandof typeSystem.Windows.Input.ICommandCommandParameterof typeObject

To use the command interface, you define a data binding that targets the Command property of the Button where the source is a property in the ViewModel of type ICommand. The ViewModel contains code associated with that ICommand property that is executed when the button is clicked. You can set CommandParameter to arbitrary data to distinguish between multiple buttons if they are all bound to the same ICommand property in the ViewModel.

The Command and CommandParameter properties are also defined by the following classes:

MenuItemand hence,ToolbarItem, which derives fromMenuItemTextCelland hence,ImageCell, which derives fromTextCellTapGestureRecognizer

SearchBar defines a SearchCommand property of type ICommand and a SearchCommandParameter property. The RefreshCommand property of ListView is also of type ICommand.

All these commands can be handled within a ViewModel in a manner that doesn't depend on the particular user-interface object in the View.

The ICommand Interface

The System.Windows.Input.ICommand interface is not part of Xamarin.Forms. It is defined instead in the System.Windows.Input namespace, and consists of two methods and one event:

public interface ICommand

{

public void Execute (Object parameter);

public bool CanExecute (Object parameter);

public event EventHandler CanExecuteChanged;

}

To use the command interface, your ViewModel contains properties of type ICommand:

public ICommand MyCommand { private set; get; }

The ViewModel must also reference a class that implements the ICommand interface. This class will be described shortly. In the View, the Command property of a Button is bound to that property:

<Button Text="Execute command"

Command="{Binding MyCommand}" />

When the user presses the Button, the Button calls the Execute method in the ICommand object bound to its Command property. That's the simplest part of the commanding interface.

The CanExecute method is more complex. When the binding is first defined on the Command property of the Button, and when the data binding changes in some way, the Button calls the CanExecute method in the ICommand object. If CanExecute returns false, then the Button disables itself. This indicates that the particular command is currently unavailable or invalid.

The Button also attaches a handler on the CanExecuteChanged event of ICommand. The event is fired from within the ViewModel. When that event is fired, the Button calls CanExecute again. The Button enables itself if CanExecute returns true and disables itself if CanExecute returns false.

Important

Do not use the IsEnabled property of Button if you're using the command interface.

The Command Class

When your ViewModel defines a property of type ICommand, the ViewModel must also contain or reference a class that implements the ICommand interface. This class must contain or reference the Execute and CanExecute methods, and fire the CanExecuteChanged event whenever the CanExecute method might return a different value.

You can write such a class yourself, or you can use a class that someone else has written. Because ICommand is part of Microsoft Windows, it has been used for years with Windows MVVM applications. Using a Windows class that implements ICommand allows you to share your ViewModels between Windows applications and Xamarin.Forms applications.

If sharing ViewModels between Windows and Xamarin.Forms is not a concern, then you can use the Command or Command<T> class included in Xamarin.Forms to implement the ICommand interface. These classes allow you to specify the bodies of the Execute and CanExecute methods in class constructors. Use Command<T> when you use the CommandParameter property to distinguish between multiple views bound to the same ICommand property, and the simpler Command class when that isn't a requirement.

Basic Commanding

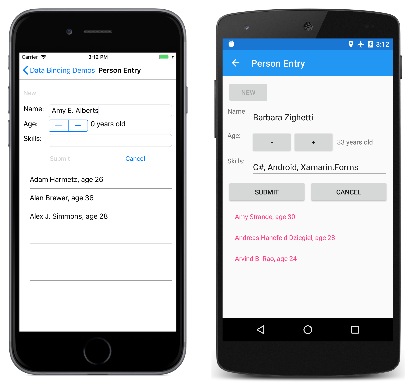

The Person Entry page in the sample program demonstrates some simple commands implemented in a ViewModel.

The PersonViewModel defines three properties named Name, Age, and Skills that define a person. This class does not contain any ICommand properties:

public class PersonViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

string name;

double age;

string skills;

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler PropertyChanged;

public string Name

{

set { SetProperty(ref name, value); }

get { return name; }

}

public double Age

{

set { SetProperty(ref age, value); }

get { return age; }

}

public string Skills

{

set { SetProperty(ref skills, value); }

get { return skills; }

}

public override string ToString()

{

return Name + ", age " + Age;

}

bool SetProperty<T>(ref T storage, T value, [CallerMemberName] string propertyName = null)

{

if (Object.Equals(storage, value))

return false;

storage = value;

OnPropertyChanged(propertyName);

return true;

}

protected void OnPropertyChanged([CallerMemberName] string propertyName = null)

{

PropertyChanged?.Invoke(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName));

}

}

The PersonCollectionViewModel shown below creates new objects of type PersonViewModel and allows the user to fill in the data. For that purpose, the class defines properties IsEditing of type bool and PersonEdit of type PersonViewModel. In addition, the class defines three properties of type ICommand and a property named Persons of type IList<PersonViewModel>:

public class PersonCollectionViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

PersonViewModel personEdit;

bool isEditing;

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler PropertyChanged;

···

public bool IsEditing

{

private set { SetProperty(ref isEditing, value); }

get { return isEditing; }

}

public PersonViewModel PersonEdit

{

set { SetProperty(ref personEdit, value); }

get { return personEdit; }

}

public ICommand NewCommand { private set; get; }

public ICommand SubmitCommand { private set; get; }

public ICommand CancelCommand { private set; get; }

public IList<PersonViewModel> Persons { get; } = new ObservableCollection<PersonViewModel>();

bool SetProperty<T>(ref T storage, T value, [CallerMemberName] string propertyName = null)

{

if (Object.Equals(storage, value))

return false;

storage = value;

OnPropertyChanged(propertyName);

return true;

}

protected void OnPropertyChanged([CallerMemberName] string propertyName = null)

{

PropertyChanged?.Invoke(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs(propertyName));

}

}

This abbreviated listing does not include the class's constructor, which is where the three properties of type ICommand are defined, which will be shown shortly. Notice that changes to the three properties of type ICommand and the Persons property do not result in PropertyChanged events being fired. These properties are all set when the class is first created and do not change thereafter.

Before examining the constructor of the PersonCollectionViewModel class, let's look at the XAML file for the Person Entry program. This contains a Grid with its BindingContext property set to the PersonCollectionViewModel. The Grid contains a Button with the text New with its Command property bound to the NewCommand property in the ViewModel, an entry form with properties bound to the IsEditing property, as well as properties of PersonViewModel, and two more buttons bound to the SubmitCommand and CancelCommand properties of the ViewModel. The final ListView displays the collection of persons already entered:

<ContentPage xmlns="http://xamarin.com/schemas/2014/forms"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2009/xaml"

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:DataBindingDemos"

x:Class="DataBindingDemos.PersonEntryPage"

Title="Person Entry">

<Grid Margin="10">

<Grid.BindingContext>

<local:PersonCollectionViewModel />

</Grid.BindingContext>

<Grid.RowDefinitions>

<RowDefinition Height="Auto" />

<RowDefinition Height="Auto" />

<RowDefinition Height="Auto" />

<RowDefinition Height="*" />

</Grid.RowDefinitions>

<!-- New Button -->

<Button Text="New"

Grid.Row="0"

Command="{Binding NewCommand}"

HorizontalOptions="Start" />

<!-- Entry Form -->

<Grid Grid.Row="1"

IsEnabled="{Binding IsEditing}">

<Grid BindingContext="{Binding PersonEdit}">

<Grid.RowDefinitions>

<RowDefinition Height="Auto" />

<RowDefinition Height="Auto" />

<RowDefinition Height="Auto" />

</Grid.RowDefinitions>

<Grid.ColumnDefinitions>

<ColumnDefinition Width="Auto" />

<ColumnDefinition Width="*" />

</Grid.ColumnDefinitions>

<Label Text="Name: " Grid.Row="0" Grid.Column="0" />

<Entry Text="{Binding Name}"

Grid.Row="0" Grid.Column="1" />

<Label Text="Age: " Grid.Row="1" Grid.Column="0" />

<StackLayout Orientation="Horizontal"

Grid.Row="1" Grid.Column="1">

<Stepper Value="{Binding Age}"

Maximum="100" />

<Label Text="{Binding Age, StringFormat='{0} years old'}"

VerticalOptions="Center" />

</StackLayout>

<Label Text="Skills: " Grid.Row="2" Grid.Column="0" />

<Entry Text="{Binding Skills}"

Grid.Row="2" Grid.Column="1" />

</Grid>

</Grid>

<!-- Submit and Cancel Buttons -->

<Grid Grid.Row="2">

<Grid.ColumnDefinitions>

<ColumnDefinition Width="*" />

<ColumnDefinition Width="*" />

</Grid.ColumnDefinitions>

<Button Text="Submit"

Grid.Column="0"

Command="{Binding SubmitCommand}"

VerticalOptions="CenterAndExpand" />

<Button Text="Cancel"

Grid.Column="1"

Command="{Binding CancelCommand}"

VerticalOptions="CenterAndExpand" />

</Grid>

<!-- List of Persons -->

<ListView Grid.Row="3"

ItemsSource="{Binding Persons}" />

</Grid>

</ContentPage>

Here's how it works: The user first presses the New button. This enables the entry form but disables the New button. The user then enters a name, age, and skills. At any time during the editing, the user can press the Cancel button to start over. Only when a name and a valid age have been entered is the Submit button enabled. Pressing this Submit button transfers the person to the collection displayed by the ListView. After either the Cancel or Submit button is pressed, the entry form is cleared and the New button is enabled again.

The iOS screen at the left shows the layout before a valid age is entered. The Android screen shows the Submit button enabled after an age has been set:

The program does not have any facility for editing existing entries, and does not save the entries when you navigate away from the page.

All the logic for the New, Submit, and Cancel buttons is handled in PersonCollectionViewModel through definitions of the NewCommand, SubmitCommand, and CancelCommand properties. The constructor of the PersonCollectionViewModel sets these three properties to objects of type Command.

A constructor of the Command class allows you to pass arguments of type Action and Func<bool> corresponding to the Execute and CanExecute methods. It's easiest to define these actions and functions as lambda functions right in the Command constructor. Here is the definition of the Command object for the NewCommand property:

public class PersonCollectionViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

···

public PersonCollectionViewModel()

{

NewCommand = new Command(

execute: () =>

{

PersonEdit = new PersonViewModel();

PersonEdit.PropertyChanged += OnPersonEditPropertyChanged;

IsEditing = true;

RefreshCanExecutes();

},

canExecute: () =>

{

return !IsEditing;

});

···

}

void OnPersonEditPropertyChanged(object sender, PropertyChangedEventArgs args)

{

(SubmitCommand as Command).ChangeCanExecute();

}

void RefreshCanExecutes()

{

(NewCommand as Command).ChangeCanExecute();

(SubmitCommand as Command).ChangeCanExecute();

(CancelCommand as Command).ChangeCanExecute();

}

···

}

When the user clicks the New button, the execute function passed to the Command constructor is executed. This creates a new PersonViewModel object, sets a handler on that object's PropertyChanged event, sets IsEditing to true, and calls the RefreshCanExecutes method defined after the constructor.

Besides implementing the ICommand interface, the Command class also defines a method named ChangeCanExecute. Your ViewModel should call ChangeCanExecute for an ICommand property whenever anything happens that might change the return value of the CanExecute method. A call to ChangeCanExecute causes the Command class to fire the CanExecuteChanged method. The Button has attached a handler for that event and responds by calling CanExecute again, and then enabling itself based on the return value of that method.

When the execute method of NewCommand calls RefreshCanExecutes, the NewCommand property gets a call to ChangeCanExecute, and the Button calls the canExecute method, which now returns false because the IsEditing property is now true.

The PropertyChanged handler for the new PersonViewModel object calls the ChangeCanExecute method of SubmitCommand. Here's how that command property is implemented:

public class PersonCollectionViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

···

public PersonCollectionViewModel()

{

···

SubmitCommand = new Command(

execute: () =>

{

Persons.Add(PersonEdit);

PersonEdit.PropertyChanged -= OnPersonEditPropertyChanged;

PersonEdit = null;

IsEditing = false;

RefreshCanExecutes();

},

canExecute: () =>

{

return PersonEdit != null &&

PersonEdit.Name != null &&

PersonEdit.Name.Length > 1 &&

PersonEdit.Age > 0;

});

···

}

···

}

The canExecute function for SubmitCommand is called every time there's a property changed in the PersonViewModel object being edited. It returns true only when the Name property is at least one character long, and Age is greater than 0. At that time, the Submit button becomes enabled.

The execute function for Submit removes the property-changed handler from the PersonViewModel, adds the object to the Persons collection, and returns everything to initial conditions.

The execute function for the Cancel button does everything that the Submit button does except add the object to the collection:

public class PersonCollectionViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

···

public PersonCollectionViewModel()

{

···

CancelCommand = new Command(

execute: () =>

{

PersonEdit.PropertyChanged -= OnPersonEditPropertyChanged;

PersonEdit = null;

IsEditing = false;

RefreshCanExecutes();

},

canExecute: () =>

{

return IsEditing;

});

}

···

}

The canExecute method returns true at any time a PersonViewModel is being edited.

These techniques could be adapted to more complex scenarios: A property in PersonCollectionViewModel could be bound to the SelectedItem property of the ListView for editing existing items, and a Delete button could be added to delete those items.

It isn't necessary to define the execute and canExecute methods as lambda functions. You can write them as regular private methods in the ViewModel and reference them in the Command constructors. However, this approach does tend to result in a lot of methods that are referenced only once in the ViewModel.

Using Command Parameters

It is sometimes convenient for one or more buttons (or other user-interface objects) to share the same ICommand property in the ViewModel. In this case, you use the CommandParameter property to distinguish between the buttons.

You can continue to use the Command class for these shared ICommand properties. The class defines an alternative constructor that accepts execute and canExecute methods with parameters of type Object. This is how the CommandParameter is passed to these methods.

However, when using CommandParameter, it's easiest to use the generic Command<T> class to specify the type of the object set to CommandParameter. The execute and canExecute methods that you specify have parameters of that type.

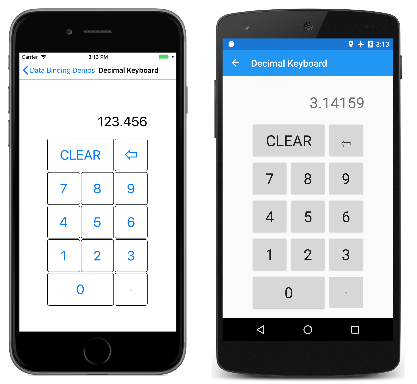

The Decimal Keyboard page illustrates this technique by showing how to implement a keypad for entering decimal numbers. The BindingContext for the Grid is a DecimalKeypadViewModel. The Entry property of this ViewModel is bound to the Text property of a Label. All the Button objects are bound to various commands in the ViewModel: ClearCommand, BackspaceCommand, and DigitCommand:

<ContentPage xmlns="http://xamarin.com/schemas/2014/forms"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2009/xaml"

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:DataBindingDemos"

x:Class="DataBindingDemos.DecimalKeypadPage"

Title="Decimal Keyboard">

<Grid WidthRequest="240"

HeightRequest="480"

ColumnSpacing="2"

RowSpacing="2"

HorizontalOptions="Center"

VerticalOptions="Center">

<Grid.BindingContext>

<local:DecimalKeypadViewModel />

</Grid.BindingContext>

<Grid.Resources>

<ResourceDictionary>

<Style TargetType="Button">

<Setter Property="FontSize" Value="32" />

<Setter Property="BorderWidth" Value="1" />

<Setter Property="BorderColor" Value="Black" />

</Style>

</ResourceDictionary>

</Grid.Resources>

<Label Text="{Binding Entry}"

Grid.Row="0" Grid.Column="0" Grid.ColumnSpan="3"

FontSize="32"

LineBreakMode="HeadTruncation"

VerticalTextAlignment="Center"

HorizontalTextAlignment="End" />

<Button Text="CLEAR"

Grid.Row="1" Grid.Column="0" Grid.ColumnSpan="2"

Command="{Binding ClearCommand}" />

<Button Text="⇦"

Grid.Row="1" Grid.Column="2"

Command="{Binding BackspaceCommand}" />

<Button Text="7"

Grid.Row="2" Grid.Column="0"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="7" />

<Button Text="8"

Grid.Row="2" Grid.Column="1"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="8" />

<Button Text="9"

Grid.Row="2" Grid.Column="2"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="9" />

<Button Text="4"

Grid.Row="3" Grid.Column="0"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="4" />

<Button Text="5"

Grid.Row="3" Grid.Column="1"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="5" />

<Button Text="6"

Grid.Row="3" Grid.Column="2"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="6" />

<Button Text="1"

Grid.Row="4" Grid.Column="0"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="1" />

<Button Text="2"

Grid.Row="4" Grid.Column="1"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="2" />

<Button Text="3"

Grid.Row="4" Grid.Column="2"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="3" />

<Button Text="0"

Grid.Row="5" Grid.Column="0" Grid.ColumnSpan="2"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="0" />

<Button Text="·"

Grid.Row="5" Grid.Column="2"

Command="{Binding DigitCommand}"

CommandParameter="." />

</Grid>

</ContentPage>

The 11 buttons for the 10 digits and the decimal point share a binding to DigitCommand. The CommandParameter distinguishes between these buttons. The value set to CommandParameter is generally the same as the text displayed by the button except for the decimal point, which for purposes of clarity is displayed with a middle dot character.

Here's the program in action:

Notice that the button for the decimal point in all three screenshots is disabled because the entered number already contains a decimal point.

The DecimalKeypadViewModel defines an Entry property of type string (which is the only property that triggers a PropertyChanged event) and three properties of type ICommand:

public class DecimalKeypadViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

string entry = "0";

public event PropertyChangedEventHandler PropertyChanged;

···

public string Entry

{

private set

{

if (entry != value)

{

entry = value;

PropertyChanged?.Invoke(this, new PropertyChangedEventArgs("Entry"));

}

}

get

{

return entry;

}

}

public ICommand ClearCommand { private set; get; }

public ICommand BackspaceCommand { private set; get; }

public ICommand DigitCommand { private set; get; }

}

The button corresponding to the ClearCommand is always enabled and simply sets the entry back to "0":

public class DecimalKeypadViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

···

public DecimalKeypadViewModel()

{

ClearCommand = new Command(

execute: () =>

{

Entry = "0";

RefreshCanExecutes();

});

···

}

void RefreshCanExecutes()

{

((Command)BackspaceCommand).ChangeCanExecute();

((Command)DigitCommand).ChangeCanExecute();

}

···

}

Because the button is always enabled, it is not necessary to specify a canExecute argument in the Command constructor.

The logic for entering numbers and backspacing is a little tricky because if no digits have been entered, then the Entry property is the string "0". If the user types more zeroes, then the Entry still contains just one zero. If the user types any other digit, that digit replaces the zero. But if the user types a decimal point before any other digit, then Entry is the string "0.".

The Backspace button is enabled only when the length of the entry is greater than 1, or if Entry is not equal to the string "0":

public class DecimalKeypadViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

···

public DecimalKeypadViewModel()

{

···

BackspaceCommand = new Command(

execute: () =>

{

Entry = Entry.Substring(0, Entry.Length - 1);

if (Entry == "")

{

Entry = "0";

}

RefreshCanExecutes();

},

canExecute: () =>

{

return Entry.Length > 1 || Entry != "0";

});

···

}

···

}

The logic for the execute function for the Backspace button ensures that the Entry is at least a string of "0".

The DigitCommand property is bound to 11 buttons, each of which identifies itself with the CommandParameter property. The DigitCommand could be set to an instance of the regular Command class, but it's easier to use the Command<T> generic class. When using the commanding interface with XAML, the CommandParameter properties are usually strings, and that's the type of the generic argument. The execute and canExecute functions then have arguments of type string:

public class DecimalKeypadViewModel : INotifyPropertyChanged

{

···

public DecimalKeypadViewModel()

{

···

DigitCommand = new Command<string>(

execute: (string arg) =>

{

Entry += arg;

if (Entry.StartsWith("0") && !Entry.StartsWith("0."))

{

Entry = Entry.Substring(1);

}

RefreshCanExecutes();

},

canExecute: (string arg) =>

{

return !(arg == "." && Entry.Contains("."));

});

}

···

}

The execute method appends the string argument to the Entry property. However, if the result begins with a zero (but not a zero and a decimal point) then that initial zero must be removed using the Substring function.

The canExecute method returns false only if the argument is the decimal point (indicating that the decimal point is being pressed) and Entry already contains a decimal point.

All the execute methods call RefreshCanExecutes, which then calls ChangeCanExecute for both DigitCommand and ClearCommand. This ensures that the decimal point and backspace buttons are enabled or disabled based on the current sequence of entered digits.

Asynchronous Commanding for Navigation Menus

Commanding is convenient for implementing navigation menus. Here's part of MainPage.xaml:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8" ?>

<ContentPage xmlns="http://xamarin.com/schemas/2014/forms"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2009/xaml"

xmlns:local="clr-namespace:DataBindingDemos"

x:Class="DataBindingDemos.MainPage"

Title="Data Binding Demos"

Padding="10">

<TableView Intent="Menu">

<TableRoot>

<TableSection Title="Basic Bindings">

<TextCell Text="Basic Code Binding"

Detail="Define a data-binding in code"

Command="{Binding NavigateCommand}"

CommandParameter="{x:Type local:BasicCodeBindingPage}" />

<TextCell Text="Basic XAML Binding"

Detail="Define a data-binding in XAML"

Command="{Binding NavigateCommand}"

CommandParameter="{x:Type local:BasicXamlBindingPage}" />

<TextCell Text="Alternative Code Binding"

Detail="Define a data-binding in code without a BindingContext"

Command="{Binding NavigateCommand}"

CommandParameter="{x:Type local:AlternativeCodeBindingPage}" />

···

</TableSection>

</TableRoot>

</TableView>

</ContentPage>

When using commanding with XAML, CommandParameter properties are usually set to strings. In this case, however, a XAML markup extension is used so that the CommandParameter is of type System.Type.

Each Command property is bound to a property named NavigateCommand. That property is defined in the code-behind file, MainPage.xaml.cs:

public partial class MainPage : ContentPage

{

public MainPage()

{

InitializeComponent();

NavigateCommand = new Command<Type>(

async (Type pageType) =>

{

Page page = (Page)Activator.CreateInstance(pageType);

await Navigation.PushAsync(page);

});

BindingContext = this;

}

public ICommand NavigateCommand { private set; get; }

}

The constructor sets the NavigateCommand property to an execute method that instantiates the System.Type parameter and then navigates to it. Because the PushAsync call requires an await operator, the execute method must be flagged as asynchronous. This is accomplished with the async keyword before the parameter list.

The constructor also sets the BindingContext of the page to itself so that the bindings reference the NavigateCommand in this class.

The order of the code in this constructor makes a difference: The InitializeComponent call causes the XAML to be parsed, but at that time the binding to a property named NavigateCommand cannot be resolved because BindingContext is set to null. If the BindingContext is set in the constructor before NavigateCommand is set, then the binding can be resolved when BindingContext is set, but at that time, NavigateCommand is still null. Setting NavigateCommand after BindingContext will have no effect on the binding because a change to NavigateCommand doesn't fire a PropertyChanged event, and the binding doesn't know that NavigateCommand is now valid.

Setting both NavigateCommand and BindingContext (in any order) prior to the call to InitializeComponent will work because both components of the binding are set when the XAML parser encounters the binding definition.

Data bindings can sometimes be tricky, but as you've seen in this series of articles, they are powerful and versatile, and help greatly to organize your code by separating underlying logic from the user interface.