Should Business Architects use the Business Model Canvas at the Program level?

In the Open Group conference at Newport Beach, I listened to a series of presentations on business architecture. In one of them, the presenter described his practice of using Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas to create a model of his program’s environment after a business program (aka business initiative) is started. He felt that the canvas is useful for creating a clear picture of the business impacts on a program. There are problems with this method, which I’d like to share in this post.

Let me lay out the context for the sake of this post since there is no business architecture “standard vocabulary.”

A “business program” is chartered by an “enterprise” to improve a series of “capabilities” in order to achieve a specific and measurable business “goal.” This business program has a management structure and is ultimately provided funding for a series of “projects.” The business architect involved in this program creates a “roadmap” of the projects and to rationalizes the capability improvements across those projects and between his program and other programs.

For folks who follow my discussions in the Enterprise Business Motivation Model, I use the term “initiative” in that model. I’m using the term “program” for this post because the Open Group presenter used the word “program.” Note that the presentation was made at an Open Group conference but it does NOT represent the opinion or position of the Open Group and is not part of the TOGAF or other deliverables of the Open Group.

The practice presented by this talk is troubling to me. As described, the practice that this presenter provided goes like this: Within the context of the program, the business architect would pull up a blank copy of the business model canvas and sit with his or her executive sponsor or steering committee to fill it out. By doing so, he or she would understand “the” business model that impacts the program.

During the Q&A period I asked about a scenario that I would expect to be quite commonplace: what if the initiative serves and supports multiple business models? The presenter said, in effect, “we only create one canvas.” My jaw dropped.

A screwdriver makes a lousy hammer but it can sometimes work. The wrong tool for the job doesn’t always fail, but it will fail often enough to indicate, to the wise, that a better tool should be found.

The Osterwalder’s business model canvas makes a very poor tool for capturing business forces from the perspective of a program. First off, programs are transitory, while business models are not. The notion of a business model is a mechanism for capturing how a LINE OF BUSINESS makes money independent of other concerns and other lines of business. Long before there is a program, and long after the program is over, there are business models, and the canvas is a reasonable mechanism for capturing one such model at a time. It is completely inappropriate for capturing two different models on a single canvas. Every example of a business model, as described both in Osterwalder’s book and on his web site, specifically describe a single business model within an enterprise.

I have no problem with using business models (although my canvas is different from Osterwalder’s). That said, I recommend a different practice: If the business initiative is doing work that will impact MULTIPLE business models, it is imperative that ALL of those business models are captured in their own canvas. The session speaker specifically rejected this idea. I don’t think he is a bad person. I think he has been hammering nails with a screwdriver. (He was young).

Here’s where he made his mistake:

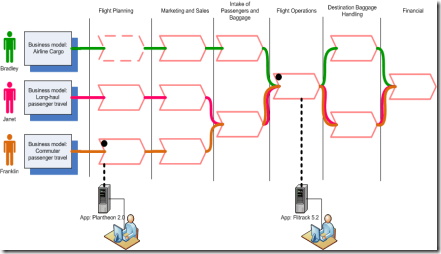

In the oversimplified value stream model above, Contoso airlines has three business models. The business owners for these three businesses are on the left: Bradley, Janet, and Franklin. Each are primarily concerned with their own business flows. In this oversimplified situation, there are only two programs, each with one project. If the session speaker were working on the Plantheon program, his idea works. there is only one business model to create. That nail can be hammered in with a screwdriver. Lucky speaker. Showing Franklin his own business model is a good thing.

But if we are working on the Flitrack program, what do we show Franklin? if we create a “generic” canvas that includes cargo, he will not recognize the model as being applicable to his concerns. He will not benefit and neither will the program. In fact, Franklin will think us fools because he had a presentation from Plantheon yesterday showing him an accurate model… don’t you people talk?

Program Flitrack should have one-on-one conversations with Bradley and Janet to develop their business models. The business model that Franklin cares about does not need to be created again. It can come out of the repository. The Flitrack program would consider all three models as independent inputs to the business architecture of the organization impacting the program.

Anything less is business analysis, not business architecture.

Comments

Anonymous

February 01, 2013

Agree on the jaw dropping... It's a Business Model Canvas not a program model canvas. A program's impact on the model can be useful to capture. Changed, Removed or New resource, capabilities, channels, etc... Basically the opposite of what he presented. Really strange. We use it to capture the current business model, what needs to be changed, why and associate influencers, strategy, initiatives (programs) or projects with that change.Anonymous

February 22, 2013

The missing piece: Alexander Osterwalder’s Business Model Canvas is a fantastic tool for anyone involved in exploring new business models. Yet, as practical as the model canvas is, using it with our clients we felt that something was missing: it is what we call “solution-independent customer problem”. We have always looked at this element independently from the product or service offered. A watch is a product with a value proposition, namely to measure time. But the customer problem of needed the precise time exists independently of the watch and can even be solved in a completely different way. This is even more applicable when we sell the watch as a luxury item or status object. It is what Clayton Christensen refers to as “The job to be done”. With Osterwalder, “The job to be done” finds its place in a separate canvas. Which is a shame, actually. Since we see innovation arising from two sides, market and technology, we have simply enhanced the model with two elements:

- The customer need with the questions: o Which customer benefits do we wish to satisfy? o What does the customer actually pay for? o What is the background of the solution to the problem? o What are the true purchasing criteria? o Which purchasing criteria are better solved by our products?

- The technological solution with the questions: o What are the existing technological solutions behind the products? o Where does our company have competencies – core competencies? o In which stage of life are these technologies? o What new inventions are pending and which customer problems could be (much) better solved with them? o Which purchasing criterium could we significantly improve? A chain then arises: customer – customer problem – technology – product, or if you prefer: product – technology – customer problem – customer. What is fascinating is that the model remains beautifully symmetrical and fits logically. We are curious to know what you think about this enancement. On our Websites you find more information about our new enhanced concept: www.furger-partner.ch and www.agility-3.com Ignaz Furger Andreas Wettstein

- Anonymous

February 26, 2013

@Ignaz and @Andreas You have identified the same problem that I did in my prior post and that Tom Graves identified in his analysis of the BMC... in the BMC, the demands of the customer are not differentiated from the value being offered to satisfy those needs. You have addressed that same problem in the same way that we have: by clearly differentiating between the two. If you look at the article that I linked in the post above (called the EA Model behind the Business Model Canvas), you will see the entire derivation of an EA model that leverages Osterwalder's intent while resulting in a different model than he uses. I don't believe it is wise to use the term "technology" though, because the value provided does not need to be related to a technology. You have limited yourself to a valuable subset of business models: those where technology is key to differentiation and value. That is great, if you are Apple. It is not so great if you are a company that differentiates on the basis if quality or service or price but NOT on technology. Realize that a model of business that is useful has to be general enough to capture a wide array of business models, while detailed enough to draw interesting and useful conclusions. Osterwalder got close but missed. He tried to make up for it with a follow-on model of demand that basically confuses everyone. Tom and I (and now you) are taking a different route: to include this key differentation in the core model itself. I will click over to your site for a little intellectual stimulation. Thanks for sharing.