This guide describes how the AI tools in Azure Cognitive Services can help you automate an offline dubbing process and ensure a high-quality dubbed version of original input.

Dubbing is the process of placing a replacement track over an original audio/video source. It includes speech-to-speech transformation from a source to a target speech stream. There are two types of dubbing. Real-time dubbing modifies the original audio/video track for the content. Offline dubbing refers to a postproduction process. The offline process enables human assistance to improve the overall outcome as compared to that of real-time implementations. You can correct errors at each stage and add enough metadata to make the output more truthful to the original. You can use the same pipeline to provide subtitles for the video track.

FFmpeg is a trademark of Fabrice Bellard.

Architecture

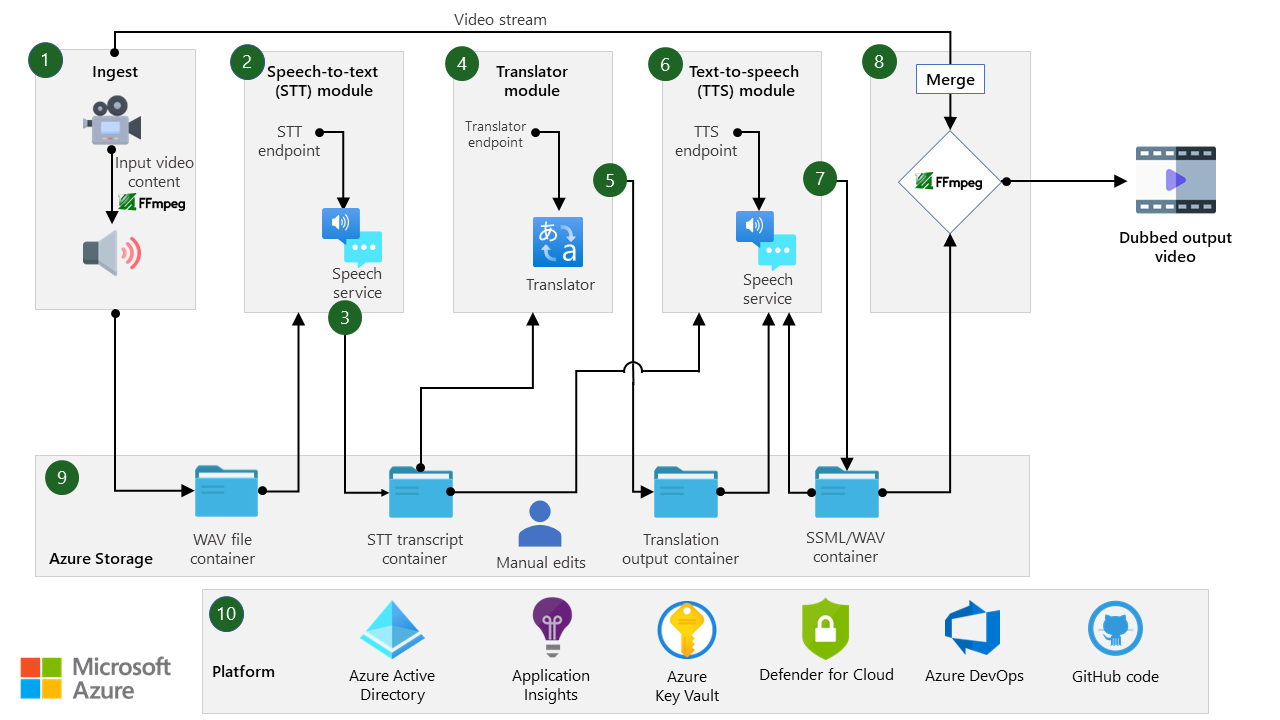

This architecture shows a pipeline that performs human-assisted speech-to-speech dubbing in offline mode. The successful completion of each module triggers the next one. The speech-to-speech pipeline contains the required elements for generating an offline dubbed audio stream. It uses the transcript of the spoken text to produce subtitles. You can optionally enhance the subtitles to produce closed captioning as well.

Download a PowerPoint file of this architecture.

Workflow

- Video ingestion: FFmpeg open-source software divides the input video content into an audio stream and a video stream. The pipeline saves the audio stream as a WAV file in WAV file container (blob storage). FFmpeg merges the video stream later in the process.

- Speech-to-text module: The speech-to-text module uses the audio file from WAV file container as input. It uses Azure Speech service to determine the language or languages of the source audio and to detect individual speakers. It transcribes the audio and saves it in text format. The speech-to-text module stores the text file, a subtitle caption file, and a word-level time stamp file in STT transcript container.

- Subtitle file production and filtering: The speech-to-text module produces the subtitle file along with notes to aid manual review of the content and correct errors introduced by the speech-to-text module. The subtitle file includes text, time stamps, and other metadata, like speaker ID and language ID, that enables the rest of the pipeline to function correctly. The pipeline stores the subtitle file in STT transcript container as a WebVTT file. It contains notes on potential points for human verification. These notes don't interfere with the ability to add the file as a subtitle file to the final output video. After the speech-to-text module produces the subtitle file, human editors can correct errors and optionally add emotion tags to reflect the input audio.

- Translator module: The translation of the text is independent of time stamps. The input subtitle text is compiled based on the speakers. The translator service requires only the text with its context to perform the mapping to the target language. The timing and placement of the audio is forwarded to the text-to-speech module in the pipeline for proper representation of the source audio in the output. This input also includes language identification of the various segments. It enables the translation service to skip segments that don't require translation. The translation module can also perform content filtering.

- Target subtitle file production: This module is responsible for reproducing the subtitle file in the target language. It does this by replacing the text in the transcribed input file. It maintains the time stamps and metadata that are associated with the text. The metadata might also include hints for the human reviewer and correct the content to improve the quality of translated text. Like the speech-to-text output, the file is a WebVTT file that's stored in Azure Storage. It includes notes that highlight potential points for human editing.

- Text-to-speech module: The Speech service converts the transcribed text from the source audio to the target speech track. The service uses Speech Synthesis Markup Language (SSML) to represent the conversion parameters of the target text. It fine-tunes pitch, pronunciation, emotion, speech rate, pauses, and other parameters in the text-to-text process. This service enables multiple customizations, including the ability to use custom neural voices. It generates the output audio files (WAV files), which are saved in blob storage for further use.

- Timing adjustment and SSML file production: The audio segments in source and target languages might be of different lengths, and the specifics for each language might differ. The pipeline adjusts the timing and positioning of the speech within the target output stream to be truthful to the source audio but still sound natural in the target language. It converts the output speech to an SSML file. It also matches the audio segments to the right speaker and provides the right tone and emotions. The pipeline produces one SSML file as output for the input audio. The SSML file is stored in Azure Storage. It highlights segments that might benefit from human revision, for both placement and rate.

- Merge: FFmpeg adds the generated WAV file to the video stream to produce a final output. The subtitles that are generated in this pipeline can be added to the video.

- Azure Storage: The pipeline uses Azure Storage to store and retrieve content as it's produced and processed. Intermediate files are editable if you need to correct errors at any stage. You can restart the pipeline from different modules to improve the final output via human verification.

- Platform: The platform components complete the pipeline, enabling enhanced security, access rights, and logging. Microsoft Entra ID and Azure Key Vault regulate access and store secrets. You can enable Application Insights to perform logging for debugging.

The pipeline is aware of errors. This awareness is significant when the language or speaker changes. The key to getting the right speech-to-text and translation output is understanding the context of the speech. You might need to check and correct the output text after each step. For certain use cases, the pipeline can perform automatic dubbing, but it's not optimized for real-time speech-to-speech dubbing. In offline mode, the full audio is processed before the pipeline continues. This enables each module to run for the full length of the audio and aligns with module design.

Components

- Azure Cognitive Services is a suite of cloud-based AI services that helps developers build cognitive intelligence into applications without having direct AI or data science skills or knowledge. The services are available through REST APIs and client library SDKs in popular development languages.

- Azure Speech service unifies speech-to-text, text-to-speech, speech translation, voice assistant, and speaker recognition functionality into a single service-based subscription offering.

- Azure translator service is a cloud-based neural machine translation service that's part of the Cognitive Services family of REST APIs. You can use it with any operating system. Translator service enables many Microsoft products and services that are used by thousands of businesses worldwide to perform language translation and other language-related operations.

Use cases

Audio dubbing is one of the most useful and widely used tools for media houses and OTT platforms. It helps increase global reach by adding relevance to content for local audiences. Offline processing works best for dubbing, but real-time dubbing can be used for some applications.

Offline dubbing

Following are some use cases in which offline audio dubbing is the best choice:

- Reproduce films and other media in a different language.

- Replace original on-set audio that isn't usable because of poor recording equipment, ambient noise, or inadequate performance by the subject.

- Implement content filtering to remove profanity or slang. Implement pronunciation correction in applicable segments to adjust content for the target audience.

- Generate subtitles. The dubbing pipeline generates a transcript from the audio/video as a byproduct of the process. You can use this transcript to generate subtitles in the original or dubbed language. You can enhance the transcribed text to produce closed captioning for media.

These scenarios have traditionally presented difficult problems that required manual intervention by trained professionals. Given recent improvements in speech and language modeling, you can inject AI modules into these processes to make them more efficient and cost effective.

Real-time dubbing

You can implement real-time dubbing with this pipeline, but it doesn't allow human intervention for corrections. Also, longer audio files might require additional processing power and time, which increases the cost of transcription. One way to handle this limitation is to divide the input into smaller segments of audio that are pushed through the pipeline as separate elements. However, this technique might present some problems:

- Dividing the input audio into smaller clips can disrupt context and reduce the quality of transcription. Default speaker ID tagging might yield inconsistent results, especially if you don't use custom models for speaker identification. Default tagging that's based on the order of appearance makes accurate speaker mapping difficult when audio is divided into fragments. You can resolve this challenge if the source audio has separate channels assigned to specific speakers.

- Timing is crucial to obtaining natural and synchronized output audio. You need to minimize latency in the production pipeline and measure it accurately. By identifying the delay caused by the pipeline and using sufficient buffer, you can ensure that the output consistently matches the pace of the input audio. You also need to account for potential pipeline failures and maintain output consistency accordingly.

Taking into account the previous points, you could use this pipeline to process real-time audio in scenarios where:

- Audio contains only one speaker who's speaking clearly in one language.

- There's no overlapping audio from multiple speakers, and there's a clear pause between any speaker or language changes.

- Different audio channels are produced for each speaker, and they can be processed independently.

Design considerations

This section describes services and features in the audio dubbing pipeline, highlighting the factors to consider to generate high-quality output. Note that this guide's implementation uses base or universal models for all cognitive models. Custom models can enhance the output of each service and the overall solution.

Speech-to-text

The performance of each module significantly influences the quality of the overall output. When the input quality deteriorates because of speech issues or background noise, errors can occur in subsequent modules, making it increasingly difficult and time-consuming to generate high-quality output that's free of errors. However, you can take advantage of various features in Speech service to minimize this problem and ensure high-quality output.

Segment the audio properly. Proper segmentation of the source audio is critical to the process of improving the overall solution. The speech-to-text module performs segmentation based on significant pauses, which is a coarse division of source audio. Additionally, the speech-to-text module divides longer segments of audio into segments that remain within the speech-to-text service. However, this segmentation introduces problems, like incorrect context and inappropriate speaker mapping.

Extract timing information. The process of dubbing involves a margin of timing misalignment that originates from the differences in how content is expressed in different languages. The speech-to-text produces timing information from the source audio, which is fundamental to the reproduction of correctly timed speech in the target language. Although it's not required in the translation of the text, the timing information needs to be passed on to the module that generates the SSML file. The granularity of the timing data remains at the segment level. And because the translation doesn't provide alignment information, the word-level timing isn't transferable to the target language. Therefore, modifications of the text input to accommodate context in translation need to be reversible.

Present audio source as one stream. The ability to distinguish speakers in the source audio is another important factor in producing correct dubbing targets. The process of partitioning an audio stream into homogeneous segments according to the identity of each speaker is called diarization. When different speaker segments aren't available as separate audio streams, the easiest way to perform consistent diarization is to present the audio source as one stream, as opposed to breaking it down into individual segments. If you present the audio in this way, the various speakers are indexed according to their order of appearance, which reduces the need to use custom speaker-identification models to identify speakers accurately.

Consider combining models. Custom models enable better speaker identification and appropriate labeling of the text produced by any specific speaker. In some cases, it might be best to mix two approaches, building speaker identification models for key speakers and diarizing the remaining speakers in order of their appearance by using the service. You can implement this method by using Azure speaker recognition to train speaker identification models for the key speakers. You would need to collect enough audio data for each key speaker. Use the text transcripts generated by Azure speech-to-text to identify speaker changes and segment the audio data into different speaker segments. Then post-process and refine the results as needed. This process might involve combining or splitting segments, adjusting segment boundaries, or correcting speaker identification errors.

The implementation details might vary depending on your specific requirements and the characteristics of your audio data. Additionally, diarization systems can be computationally intensive, so you need to consider the processing speed of your speech-to-text model. You might need to use a model that's optimized for speed or use parallel-processing techniques to speed up the diarization process.

Use the lexical text to reduce potential errors generated by the ITN. Speech-to-text provides an array of formatting features to ensure that the transcribed text is legible and appropriate. Speech-to-text produces several representations of the input speech, each with different formatting. The recognized text obtained after disfluency removal, inverse text normalization (ITN), punctuation, capitalization, profanity filter, and so on, is called display text. The display text improves the readability of the text and uses pre-built models to define how to display different components. For example, the display format might include the use of capital letters for proper nouns or the insertion of commas to separate phrases. This format should be moved forward in the pipeline because it helps provide context in the translation and minimizes the need to reformat the text.

The words recognized by the service appear in a format known as the lexical format. The lexical format includes factors like the spelling of words and the use of homophones. The architecture uses this format to assess the extent of human intervention that's needed for correction on the speech-to-text output. This format represents the actual recognition of the speech-to-text service, and the formatting doesn't mask mismatched recognition. For example, the lexical format might represent the word "there" as "their" if the context suggests that it's the intended meaning.

Filter profanity later in the pipeline. Speech-to-text provides profanity filtering as an option. The architecture presented here doesn't use profanity filtering. You can enable profanity filtering via the display formatting settings. It's better to avoid using this filtering early in the pipeline because it might introduce some loss of context and result in mismatches as the pipeline proceeds. However, the filtering affects the display text and MaskedITN, not the lexical format in the speech-to-text output.

Consider creating a joint-language model when you use a custom model. Speech service provides a language identification feature. To use this feature, you need to define, beforehand, the locales that are relevant to the input audio. Language identification requires some context, and sometimes there's a lag in flagging a language change. If you use custom models, consider creating a joint-language model, where the model is trained with utterances from multiple languages. This approach is useful for handling speech from regions where it's common to use two different languages together, like Hinglish, which contains both Hindi and English.

Ensure clear turn-taking and natural pauses between speakers. Like language switching, user switching also works best when the speakers take turns and there's a natural pause between speakers. If there are overlapping conversations or a short pause between speakers and the audio is bundled into one channel, the speech-to-text output might contain errors that require human intervention. Background speech that might not be the focus of the content but that affects the output quality can cause similar errors. Correcting these errors requires word-level timing to identify the appropriate offsets for various speakers.

Translator service

The translator service provides features that you can use to generate higher-quality output.

Maintain enough context. The main point to consider when you use the translator service is how much context to present in order to produce an accurate translation. To help with accurate translation, consider bundling the text from the same speaker ID, within a meaningful timespan if the context is observed appropriately. Note that speech-to-text divides the input audio based on meaningful pauses, but, for longer monologues, the audio is divided at approximately 30-second segments. This segmentation might result in some loss of context. Also, overlapping speech from different speakers might disturb the context and produce a poor translation output. Therefore, human intervention is frequently indispensable during this step.

Consider skipping segments in multilingual sources. In some cases, input includes multiple languages and some segments don't require translation. For example, the source and target locales might match, or terminology or jargon might be used as is. To skip languages that you don't want to translate, each segment needs to define the source and target locales for the translator service. The service needs a configuration file that defines languages that shouldn't be translated. To reduce costs, consider filtering out segments that don't require translation so that you don't input them into the translator service.

Filter caption profanity independently. Like speech-to-text, the translator service enables you to filter profanity. Masking or marking content for profanity can make captions more appropriate to the target audience. However, removing content via profanity filtering might confuse the timing analysis and placement of the speech output by the service. It might also lead to misinterpretations of the context. You should consider independently producing the captions file that's filtered for profanity.

Ensure accurate timing alignment in captions. Although the speech-to-text output produces word-level time stamps, the translator service doesn't match the time stamps with alignment data. Therefore, the time stamps in the captions file in WebVTT format remain the same as the time stamps in the source file. This might present marginal misalignment in the presentation of captions because translating to a different language might reduce or increase the length of the content.

Text-to-speech

Select appropriate voices. Based on the type of content and the intended audience, the selection of a speaker voice can have a significant influence on how well the content is received. The service provides pre-built voices in a range of languages in male and female voices. It also provides pre-built models that allow injection of emotions. Alternatively, you can use a custom neural voice that's available in two versions, Lite and Pro, for the target speech language. If you use the Pro version, you can add emotions to the voice to model the source speech input. In all cases, you need to define a voice for each speaker and for each language. Unless you check the speech-to-text output to ensure that there are no unidentified speakers, you need to define a default voice.

Perform speech placement. The placement of the target speech and the integration of it into one SSML file are key elements in the text-to-text module. The following sections describe these elements.

Integrate SSML files accurately. SSML enables you to customize text-to-text output with identifying details on audio formation, speakers, pauses, and timing placement of the target audio. You can use it to format text-to-text output attributes like pitch, pronunciation, rate, and emotion. For more information, see Speech synthesis markup.

The proper formation of the SSML file requires the timing information and the voice selection for a given segment. Therefore, everything needs to be returned to the correct segment of the source audio, and any change that's made along the pipeline should be snapped to these segments. Because the translation service doesn't produce timing information, the only source of timing details is the speech-to-text output. Additionally, the only elements that are transferable are the segment timing and the offsets that should be used to determine the duration of the target audio, in addition to the breaks and pauses in between. All this information should be carried forward to the remaining components in the pipeline, and the adjustment should be performed at the timing of the target audio as indicated previously.

Splitting the outputs by using the voice tag introduces a leading and trailing silence. You can define a value for the silence in the voice tag. In the following example, the gap between two speech segments is 450 ms (300 ms trailing and 150 ms leading). You need to account for these gaps when you calculate the final placement of the output. Here's a sample SSML element that defines some of these details:

<speak version="1.0" xmlns=http://www.w3.org/2001/10/synthesis xml:lang="en-US">

<voice name="en-US-JennyNeural">

<mstts:silence type=" Leading-exact" value="100ms"/> <mstts:silence type="Sentenceboundary-exact" value="200ms"/> <mstts:silence type="Tailing-exact" value="300ms"/>

If we're home schooling, the best we can do is roll with what each day brings and try to have fun along the way.

</voice>

<voice name="en-US-JennyNeural">

<mstts:silence type=" Leading-exact" value="150ms"/> <mstts:silence type="Sentenceboundary-exact" value="250ms"/> <mstts:silence type="Tailing-exact" value="350ms"/>

A good place to start is by trying out the slew of educational apps that help children stay happy and smash their schooling at the same time.

</voice>

</speak>

Generate separate SSML files for each speaker. The formatting of the SSML file allows you to define relative times for different voice segments. The value must be a positive value. For example, this XML defines a break after the spoken text is produced:

<speak version="1.0" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2001/10/synthesis" xml:lang="en-US">

<voice name="en-US-JennyNeural">

Welcome to Microsoft Cognitive Services <break time="100ms" /> Text-to-Speech API.

</voice>

</speak>

When multiple speakers speak concurrently, this technique doesn't work. One option is to generate a separate SSML file for every speaker (or in combinations that don't overlap) and overlay these files after the audio is produced.

Include background audio effects in a separate channel. The background noise in the source audio doesn't propagate through this pipeline, so the composition of the SSML file doesn't include it in the final output. You need to present any applicable background sound effects in a separate channel. You then add it to the final text-to-text output by using external tools.

Add emotions and styles manually to enhance voice synthesis. Emotions and tones aren't detected in source audio, so they're not propagated through the pipeline and don't appear in the SSML file. You need to add these details manually. It's best to add them in the source WebVTT output and present them as information carried over in the WebVTT notes. The emotion and style details are added as notes like all the other information in the element and parsed when the SSML is produced. You can improve the synthesis of the voices either by presenting different models for different emotions or by using the Pro Custom Neural Voice capability.

Timing placement and adjustment

Translating speech into different languages usually introduces a difference in the length of the content. You need to consider the placement and adjustment of the output speech to accommodate for this difference. Some of the ways to perform this adjustment are suggested here.

Adjust the speech rate dynamically based on source and target language rates. Matching the target speech to the duration of the source is a straightforward approach. This approach requires running the text-to-text once to determine the duration of the target text when it's converted to speech. The final rate used to produce the actual target audio reflects the ratio of the target text duration relative to the original source time for the same segment.

This approach is simple and produces a variable rate for each speech segment. The output sounds unnatural. The actual rate of the speaker in the source might change to present audible effects. You can improve the output by measuring the rate relative to a standard rate for the language and then adjusting the rate to reflect the source. You don't try to fit it into the same time span. To make this adjustment, you use the average word and character count per minute for normal speech in the source language. These counts are compared to the output of speech-to-text and used to identify the rate of the source speaker in each segment. You then use this rate in the target language. The natural rate of speakers in the target language should be incorporated in the text-to-text module. You can also set limits on the rate to make sure that the produced audio output is within controlled limits. The following code implements this process:

internal static double GetRelativeTargetRate(PreProcessTTSInput input, IOrchestratorLogger<TestingFrameworkOrchestrator> logger)

{

string sourceLanguage = input.IdentifiedLocale.Split('-')[0];

string targetLanguage = input.TargetLocale.Split('-')[0];

double maxTargetRate = input.PreProcessingStepConfig.MaxSpeechRate;

double minTargetRate = input.PreProcessingStepConfig.MinSpeechRate;

if (SpeechRateLookup.Rate.ContainsKey(sourceLanguage) && SpeechRateLookup.Rate.ContainsKey(targetLanguage))

{

try

{

// Look up values from static table

double sourceWordRate = SpeechRateLookup.Rate[sourceLanguage].WordRate;

double targetWordRate = SpeechRateLookup.Rate[targetLanguage].WordRate;

double sourceCharRate = SpeechRateLookup.Rate[sourceLanguage].CharRate;

double targetCharRate = SpeechRateLookup.Rate[targetLanguage].CharRate;

int sourceWordCount = input.LexicalText.Split(" ").Length;

int sourceCharCount = input.LexicalText.Length;

// Calculate the rate of the source segment relative to the nominal language rate

double sourceRelativeWordRate = ((sourceWordCount / input.Duration.TotalMinutes) / sourceWordRate);

double sourceRelativeCharRate = ((sourceCharCount / input.Duration.TotalMinutes) / sourceCharRate);

double sourceAverageRelativeRate = (sourceRelativeWordRate + sourceRelativeCharRate) / 2.0;

// Calculate the ratio between the target and source nominal rates

double averagedLanguageRateRatio = (((targetWordRate / sourceWordRate) + (targetCharRate / sourceCharRate)) / 2.0);

// Scale the target rate based on the source/target ratio and the relative rate of input with respect to the nominal source rate

double relativeTargetRate = sourceAverageRelativeRate / averagedLanguageRateRatio;

relativeTargetRate = Math.Min(relativeTargetRate, maxTargetRate);

relativeTargetRate = Math.Max(relativeTargetRate, minTargetRate);

return relativeTargetRate;

}

catch (DivideByZeroException exception)

{

logger.LogError(exception.Message);

return 1.0;

}

}

else

{

return 1.0;

}

}

Adjust the pauses and timing to achieve natural-sounding text-to-speech output. If the target language's speech duration is longer, use the pauses between speech segments in the original audio to accommodate the extra duration. Doing so might slightly reduce the pause between sentences, but it ensures a more natural speech rate.

Align the produced audio with the original one. You can do this at the beginning, middle, or end of the original audio. For this example, assume that you align the audio segment in the target output with the middle of the original audio span.

You can estimate the speech signal duration from the number of tokens or characters in the target language. Alternatively, make a first pass with the text-to-speech service to determine the exact duration. Because the audio is centered, distribute the difference between the target and source audio duration evenly across the two pauses before and after the original audio.

If the target audio doesn't overlap with any other audio in the target, placing it is straightforward. The new offset in the target audio is the original offset minus half the difference between the target and source audio duration, as shown here:

offsetti = offsetsi - (tti – tsi)/2

However, multiple audio segments in the target audio might overlap. The goal of this process is to correct this problem, considering only the previous segment. Following are the possible scenarios in which this overlap can occur:

- offsetti > offsett(i-1) + tt(i-1). In this scenario, both segments fit within the pause assigned between them in the original audio with no issues.

- offsetti = offsett(i-1) + tt(i-1). In this scenario, there's no pause between two consecutive audio segments in the target language. Add a small offset (enough for one word in the language) to the offsetti (Δtt). (Δtt) is to avoid continuous audio in the target audio that isn't present in the original.

- offsetti < offsett(i-1) + tt(i-1). In this case, the two audio segments overlap. There are two possible scenarios:

- offsets(i-1) + ts(i-1) < median {offsets(i-1) + ts(i-1)}∀i. In this case, the pause is shorter than the nominal pause in the video. You can shift the translated text to resolve the problem. You can assume that the longer pauses make up for the overlap. Therefore, offsetti = offsett(i-1) + tt(i-1) + Δtt.

- offsets(i-1) + ts(i-1) > median {offsets(i-1) + ts(i-1)}∀i. In this case, the pause is longer than the nominal pause in the video, but it doesn't fit the translated audio. You can use the rate to adjust the segment to be more appropriately timed. You can use this equation to calculate the new rate: rateti = rateti * (((offsett(i-1) + tt(i-1)) - offsetti) + tti + Δtt )/( tti).

Implementing this process might cause the last segment to run longer than the time of the original audio, especially if the video ends at the end of the original audio but the target audio is longer. In this situation, you have two choices:

- Let the audio run longer.

- Add the full offset of the target audio to the pre-offset, to make the last offsettn = offsetsn - (ttn – tsn). If this offset overlaps with the audio from the previous segment, use the rate modification described previously.

Aligning audio segments to the middle is appropriate in translation scenarios in which the target text is longer than the original. If the target is always faster than the original, it might be better to align the timing to the beginnings of the original audio segments.

private List<PreProcessTTSInput> CompensatePausesAnchorMiddle(List<PreProcessTTSInput> inputs)

{

logger.LogInformation($"Performing Text to Speech Preprocessing on {inputs.Count} segments.");

foreach (var input in inputs)

{

ValidateInput(input);

double rate = PreprocessTTSHelper.GetRelativeTargetRate(input, logger);

input.Rate = rate;

}

TimeSpan medianPause = PreprocessTTSHelper.CalculateMedianPause(inputs);

// Setting nominal pause as average spoken duration of an English word

TimeSpan nominalPause = new TimeSpan(0, 0, 0, 0, (int)(60.0 / 228.0 * 1000.0));

string targetLanguage = inputs[0].TargetLocale.Split('-')[0];

if (SpeechRateLookup.Rate.ContainsKey(targetLanguage))

{

nominalPause = new TimeSpan(0, 0, 0, 0, (int)(60.0 / SpeechRateLookup.Rate[targetLanguage].WordRate * 1000));

}

TimeSpan previous_target_offset = new TimeSpan(0);

TimeSpan previous_target_duration = new TimeSpan(0);

TimeSpan previous_source_offset = new TimeSpan(0);

TimeSpan previous_source_duration = new TimeSpan(0);

foreach (PreProcessTTSInput source_segment in inputs)

{

var source_duration = source_segment.Duration;

var source_offset = source_segment.Offset;

var target_duration = PreprocessTTSHelper.GetTargetDuration(source_segment);

var target_offset = source_offset - (target_duration - source_duration) / 2;

if (target_offset == previous_target_offset + previous_target_duration)

{

target_offset += nominalPause;

source_segment.HumanInterventionRequired = true;

source_segment.HumanInterventionReason = "After translation this segment just fit in the space available, a small pause was added before it to space it out.";

}

else if (target_offset < previous_target_offset + previous_target_duration)

{

source_segment.HumanInterventionRequired = true;

var previous_pause = source_segment.Offset - previous_source_offset + previous_source_duration;

if (previous_pause < medianPause)

{

target_offset = previous_target_offset + previous_target_duration + nominalPause;

source_segment.HumanInterventionReason = "After translation this segment overlapped with previous segment, but since the pause before this segment in the source was relatively small, this segment was NOT sped up and was placed right after the previous segment with a small pause";

}

else

{

var target_rate = source_segment.Rate * ((previous_target_offset + previous_target_duration - target_offset) + target_duration + nominalPause) / target_duration;

source_segment.Rate = target_rate;

target_duration = PreprocessTTSHelper.GetTargetDuration(source_segment);

target_offset = previous_target_offset + previous_target_duration + nominalPause;

source_segment.HumanInterventionReason = "After translation this segment overlapped with previous segment, also the pause this segment in the source was relatively large (and yet the translated segment did not fit), hence this segment was sped up and placed after the previous segment with a small pause";

}

}

source_segment.Offset = target_offset;

previous_target_offset = target_offset;

previous_target_duration = target_duration;

previous_source_offset = source_offset;

previous_source_duration = source_duration;

}

return inputs;

}

Creating WebVTT files for captions and human editing

Web Video Text Tracks Format (WebVTT) is a format for displaying timed text tracks, like subtitles or captions. It's used for adding text overlays to video. The WebVTT file presents the output of the pipeline for human consumption. It's also used for the captions file. This section describes some considerations for using WebVTT in this pipeline.

Include information in the notes of the WebVTT file. The WebVTT file should contain all the information that's required to process the various modules. In addition to timing and textual information, it includes the language ID, the user ID, and flags for human intervention. To include these details in the WebVTT file and keep it compatible for use as a captions/subtitles file, use the NOTE section of each segment in the WebVTT file. The following code shows the recommended format:

NOTE

{

"Locale": "en-US",

"Speaker": null,

"HumanIntervention": true,

"HumanInterventionReasons": [

{

"Word": "It's",

"WordIndex": 3,

"ContentionType": "WrongWord"

}

]

}

1

00:00:00.0600000-->00:00:04.6000000

- Hello there!

- It's a beautiful day

Ensure that subtitles display correctly on various screen sizes. When you produce captions files, you need to consider the number of words and lines of text to display on the screen. You need to consider this specifically for each individual use case during the production of the WebVTT file. Humans in the loop review these files and use prompts to resolve problems. The file also contains metadata that other modules later in the pipeline need in order to function.

To ensure that subtitles appear properly, you need to divide longer segments (transcribed or translated results) into multiple VTTCues. You need to preserve the notes and other details so that they still point to the right context and ensure that the pipeline doesn't interrupt the translation or the text-to-text placement of text.

When you divide the original text segment into multiple VTTCues, you also need to consider the timing for each division. You can use the word-level time stamps that are produced during transcription for this purpose. Because the WebVTT file is open for modification, you can update these time stamps manually, but the process creates considerable maintenance overhead.

Identify potential for human intervention

The dubbing pipeline includes three important modules: speech-to-text, translation, and text-to-speech. Errors can occur in each of these modules, and errors can propagate and become more pronounced later in the pipeline. We strongly recommend that you include human intervention to review and rectify results to ensure an acceptable level of quality. You can save significant time by identifying the specific areas that require intervention. This section describes potential errors in each module that require manual intervention.

Speech-to-text

The output of speech-to-text can be affected by the audio itself, the background noise, and the language model. You can improve audio content by customizing the language model to better suit the input. Consider the following options, depending on which points of human intervention are available in your scenario:

Identify transcription errors. The speech-to-text system can sometimes produce transcription errors. It provides multiple transcription options, each with a confidence score. These scores can help you determine the most accurate transcription. The n-best list contains the most probable hypotheses for a given speech input. The top hypothesis in this list has the highest score, indicating its likelihood of being the correct transcription. For example, a score of 0.95 indicates 95% confidence in the accuracy of the top hypothesis. By comparing the scores and differences among the outputs, you can identify discrepancies that require human intervention. You need to consider the threshold and majority voting when you review the n-best list:

Set a higher threshold for improved quality in the dubbing pipeline. The threshold plays a crucial role in identifying potential errors in the n-best results. It determines the number of n-best results that are compared during the process. A higher threshold returns more n-best results for comparison, resulting in a higher quality of intervention. Setting the threshold to zero limits the selection of candidates but provides higher confidence, as compared to the transcription produced by the speech-to-text system.

Balance recall and precision. When you use majority voting, select the lexical form for each candidate that falls within the threshold. Next, determine the insertions, deletions, and replacements in relation to the output phrase. You need to consider these points of contention for highlighting, but highlighting all of them prioritizes recall at the expense of lower precision. To enhance precision, order the insertions, deletions, and replacements based on a normalized average score. The count of these errors, relative to the total number of candidates minus one, serves as a weight. You can set a threshold to calibrate the desired precision level. A weight of 0 prioritizes recall, indicating that the error is present in at least one candidate. Conversely, a weight of 1 prioritizes precision, implying that the error appears in all candidates. In this pipeline, you need to find the appropriate balance between recall and precision.

public string EvaluateCorrectness(SpeechCorrectnessInput input)

{

var speechOutputSegments = input.Input;

var ConfidenceThreshold = input.Configuration.ConfidenceThreshold;

var errorOccurrenceThreshold = input.Configuration.OccurrenceThreshold;

var speechCorrectnessOutputSegments = new List<SpeechCorrectnessOutputSegment>();

foreach (var speechOutputSegment in speechOutputSegments)

{

// Filter the candidates within the lower confidence candidate threshold

var filteredCandidates = GetFilteredCandidates(speechOutputSegment,ConfidenceThreshold);

ICollection<SpeechPointOfContention> interventions = null;

if (filteredCandidates.Count > 0)

{

// Calculate the possible reasons for needed intervention based on the selected text, the filtered candidates, and the error threshold

interventions = CalculateInterventionReasons(speechOutputSegment.LexicalText, filteredCandidates, errorOccurrenceThreshold);

}

// Build the speech correctness segment

SpeechCorrectnessOutputSegment correctionSegment = new SpeechCorrectnessOutputSegment()

{

SegmentID = speechOutputSegment.SegmentID

};

if (interventions != null && interventions.Count > 0)

{

correctionSegment.InterventionNeeded = true;

correctionSegment.InterventionReasons = interventions;

}

else

{

correctionSegment.InterventionNeeded = false;

correctionSegment.InterventionReasons = null;

}

speechCorrectnessOutputSegments.Add(correctionSegment);

}

return JsonConvert.SerializeObject(speechCorrectnessOutputSegments);

}

private ICollection<SpeechPointOfContention> CalculateInterventionReasons(string selectedText, ICollection<SpeechCandidate> candidates, double errorOccurrenceThreshold)

{

ICollection<ICollection<ICollection<SpeechPointOfContention>>> allPossiblePointsOfContention = new List<ICollection<ICollection<SpeechPointOfContention>>>();

foreach (var candidate in candidates)

{

// Get points of contention for all speech candidates in this segment, compared to the text selected

var candidateSentence = candidate.LexicalText.Split(' ');

var segmentSentence = selectedText.Split(' ');

var editDistanceResults = CalculateEditDistance(candidateSentence, segmentSentence);

var allPossibleCandidatePointsOfContention = GetAllPossiblePointsOfContention(

candidateSentence,

segmentSentence,

new Stack<SpeechPointOfContention>(),

editDistanceResults);

allPossiblePointsOfContention.Add(allPossibleCandidatePointsOfContention);

}

// Calculate which combination of all possible points of contention will lead to the highest count for the selected points of contention across all candidates

var bestCandidatePointsOfContention = GetBestContentionCombination(allPossiblePointsOfContention);

// Keep count of occurrences of all points of contention across the candidates

var candidatePOCCounts = new Dictionary<SpeechPointOfContention, int>();

foreach (var pointsOfContention in bestCandidatePointsOfContention)

{

CountPointsOfContention(pointsOfContention, candidatePOCCounts);

}

var filteredPointsOfContention = new List<SpeechPointOfContention>();

foreach (var pocToCount in candidatePOCCounts)

{

// For each point of contention, calculate its rate of occurrence relative to the number of candidates

var occurrenceRate = (double)pocToCount.Value / candidates.Count;

// If the rate of occurrence is within the threshold, count the point of contention as an error that requires intervention

if (occurrenceRate >= errorOccurrenceThreshold)

{

filteredPointsOfContention.Add(pocToCount.Key);

}

}

return filteredPointsOfContention;

}

Implement well-spaced language transition detection. In language identification, detecting a transition from one language to another involves identifying multiple words. When the transition occurs within a certain number of tokens from the previous text, it's flagged. This assumption is based on the assumption that well-spaced segments are more likely to be detected accurately. The aim is to avoid false negatives, where a language change occurs but the speech-to-text system fails to detect it before shifting back to the original language.

Flag unidentified speaker IDs. When you use speech-to-text with diarization, the system might label some speaker IDs as Unidentified. This labeling typically occurs when a speaker speaks for a short time. We recommend that you flag these labels for human editing.

Translation

The BLEU score is a commonly used metric for evaluating the quality of translated output. However, the BLEU score has limitations. It relies on comparing the machine-translated output with human-generated reference translations to measure similarity. This metric doesn't consider important elements like fluency, grammar, and the preservation of meaning.

You can use an alternative method to assess translation quality. It involves performing a bidirectional translation and comparing the results. First, translate the input segment from the source language to the target language. Next, reverse the process and translate back from the target language to the source language. This process generates two strings: the source segment (Si) and the expected value of the source (E(Si)). By comparing the two strings, you can figure out the number of insertions and deletions.

If the number of insertions and deletions exceeds a predefined threshold, the statement is flagged for further examination. If the number falls below the threshold, the segment Si is considered a well-translated match. In cases where differences are found, it might be beneficial to highlight them in the source language. This approach helps draw attention to specific terms that need correction, rather than showing that the entire segment requires human verification.

Text-to-speech

The text-to-speech highlighting is mostly associated with the changed rate and with shifts in placement that are beyond the gaps in the source audio. The locations where there are alterations of rate or placement, as pointed out in the text-to-text section, are highlighted.

Contributors

This article is maintained by Microsoft. It was originally written by the following contributors.

Principal author:

- Nayer Wanas | Principal Software Engineer

Other contributors:

- Mick Alberts | Technical Writer

- Vivek Chettiar | Software Engineer II

- Bernardo Chuecos Rincon | Software Engineer II

- Pratyush Mishra | Principal Engineering Manager

To see non-public LinkedIn profiles, sign in to LinkedIn.

Next steps

- Sample implementation of offline audio dubbing

- What is Azure Cognitive Services?

- Language and voice support for the Speech service