Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

Introduction

This tutorial teaches you features in .NET and the C# language. You learn how to:

- Generate sequences with LINQ.

- Write methods that you can easily use in LINQ queries.

- Distinguish between eager and lazy evaluation.

You learn these techniques by building an application that demonstrates one of the basic skills of any magician: the faro shuffle. A faro shuffle is a technique where you split a card deck exactly in half, and then the shuffle interleaves each card from each half to rebuild the original deck.

Magicians use this technique because every card is in a known location after each shuffle, and the order is a repeating pattern.

This tutorial offers a lighthearted look at manipulating sequences of data. The application constructs a card deck, performs a sequence of shuffles, and writes the sequence out each time. It also compares the updated order to the original order.

This tutorial has multiple steps. After each step, you can run the application and see the progress. You can also see the completed sample in the dotnet/samples GitHub repository. For download instructions, see Samples and Tutorials.

Prerequisites

- The latest .NET SDK

- Visual Studio Code editor

- The C# DevKit

Create the application

Create a new application. Open a command prompt and create a new directory for your application. Make that the current directory. Type the command dotnet new console -o LinqFaroShuffle at the command prompt. This command creates the starter files for a basic "Hello World" application.

If you've never used C# before, this tutorial explains the structure of a C# program. You can read that and then return here to learn more about LINQ.

Create the data set

Tip

For this tutorial, you can organize your code in a namespace called LinqFaroShuffle to match the sample code, or you can use the default global namespace. If you choose to use a namespace, make sure all your classes and methods are consistently within the same namespace, or add appropriate using statements as needed.

Consider what constitutes a deck of cards. A deck of playing cards has four suits, and each suit has 13 values. Normally, you might consider creating a Card class right away and populating a collection of Card objects by hand. With LINQ, you can be more concise than the usual way of creating a deck of cards. Instead of creating a Card class, create two sequences to represent suits and ranks. Create a pair of iterator methods that generate the ranks and suits as IEnumerable<T>s of strings:

static IEnumerable<string> Suits()

{

yield return "clubs";

yield return "diamonds";

yield return "hearts";

yield return "spades";

}

static IEnumerable<string> Ranks()

{

yield return "two";

yield return "three";

yield return "four";

yield return "five";

yield return "six";

yield return "seven";

yield return "eight";

yield return "nine";

yield return "ten";

yield return "jack";

yield return "queen";

yield return "king";

yield return "ace";

}

Place these methods under the Console.WriteLine statement in your Program.cs file. These two methods both use the yield return syntax to produce a sequence as they run. The compiler builds an object that implements IEnumerable<T> and generates the sequence of strings as they're requested.

Now, use these iterator methods to create the deck of cards. Place the LINQ query at the top of the Program.cs file. Here's what it looks like:

var startingDeck = from s in Suits()

from r in Ranks()

select (Suit: s, Rank: r);

// Display each card that's generated and placed in startingDeck

foreach (var card in startingDeck)

{

Console.WriteLine(card);

}

The multiple from clauses produce a SelectMany, which creates a single sequence from combining each element in the first sequence with each element in the second sequence. The order is important for this example. The first element in the first source sequence (Suits) is combined with every element in the second sequence (Ranks). This process produces all 13 cards of first suit. That process is repeated with each element in the first sequence (Suits). The end result is a deck of cards ordered by suits, followed by values.

Keep in mind that whether you write your LINQ in the query syntax used in the preceding sample or use method syntax instead, it's always possible to go from one form of syntax to the other. The preceding query written in query syntax can be written in method syntax as:

var startingDeck = Suits().SelectMany(suit => Ranks().Select(rank => (Suit: suit, Rank: rank )));

The compiler translates LINQ statements written with query syntax into the equivalent method call syntax. Therefore, regardless of your syntax choice, the two versions of the query produce the same result. Choose the syntax that works best for your situation. For instance, if you're working in a team where some members have difficulty with method syntax, try to prefer using query syntax.

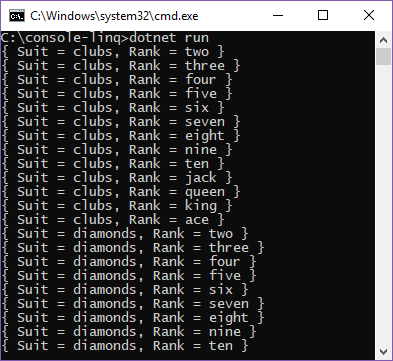

Run the sample you built at this point. It displays all 52 cards in the deck. You might find it helpful to run this sample under a debugger to observe how the Suits() and Ranks() methods execute. You can clearly see that each string in each sequence is generated only as needed.

Manipulate the order

Next, focus on how you shuffle the cards in the deck. The first step in any good shuffle is to split the deck in two. The Take and Skip methods that are part of the LINQ APIs provide that feature. Place them following the foreach loop:

var top = startingDeck.Take(26);

var bottom = startingDeck.Skip(26);

However, there's no shuffle method to take advantage of in the standard library, so you need to write your own. The shuffle method you create illustrates several techniques that you use with LINQ-based programs, so each part of this process is explained in steps.

To add functionality to how you interact with the IEnumerable<T> results of LINQ queries, you write some special kinds of methods called extension methods. An extension method is a special purpose static method that adds new functionality to an already-existing type without having to modify the original type you want to add functionality to.

Give your extension methods a new home by adding a new static class file to your program called Extensions.cs, and then start building out the first extension method:

public static class CardExtensions

{

extension<T>(IEnumerable<T> sequence)

{

public IEnumerable<T> InterleaveSequenceWith(IEnumerable<T> second)

{

// Your implementation goes here

return default;

}

}

}

Note

If you're using an editor other than Visual Studio (such as Visual Studio Code), you might need to add using LinqFaroShuffle; to the top of your Program.cs file for the extension methods to be accessible. Visual Studio automatically adds this using statement, but other editors might not.

The extension container specifies the type being extended. The extension node declares the type and name of the receiver parameter for all members inside the extension container. In this example, you're extending IEnumerable<T>, and the parameter is named sequence.

Extension member declarations appear as though they're members of the receiver type:

public IEnumerable<T> InterleaveSequenceWith(IEnumerable<T> second)

You call the method as though it were a member method of the extended type. This method declaration also follows a standard idiom where the input and output types are IEnumerable<T>. That practice enables LINQ methods to be chained together to perform more complex queries.

Since you split the deck into halves, you need to join those halves together. In code, this means you enumerate both of the sequences you acquired through Take and Skip at once, interleaving the elements, and creating one sequence: your now-shuffled deck of cards. Writing a LINQ method that works with two sequences requires that you understand how IEnumerable<T> works.

The IEnumerable<T> interface has one method: GetEnumerator. The object returned by GetEnumerator has a method to move to the next element and a property that retrieves the current element in the sequence. You use those two members to enumerate the collection and return the elements. This Interleave method is an iterator method, so instead of building a collection and returning the collection, you use the yield return syntax shown in the preceding code.

Here's the implementation of that method:

public IEnumerable<T> InterleaveSequenceWith(IEnumerable<T> second)

{

var firstIter = sequence.GetEnumerator();

var secondIter = second.GetEnumerator();

while (firstIter.MoveNext() && secondIter.MoveNext())

{

yield return firstIter.Current;

yield return secondIter.Current;

}

}

Now that you wrote this method, go back to the Main method and shuffle the deck once:

var shuffledDeck = top.InterleaveSequenceWith(bottom);

foreach (var c in shuffledDeck)

{

Console.WriteLine(c);

}

Comparisons

Determine how many shuffles it takes to set the deck back to its original order. To find out, write a method that determines if two sequences are equal. After you have that method, place the code that shuffles the deck in a loop, and check to see when the deck is back in order.

Writing a method to determine if the two sequences are equal should be straightforward. It's a similar structure to the method you wrote to shuffle the deck. However, this time, instead of using yield return for each element, you compare the matching elements of each sequence. When the entire sequence is enumerated, if every element matches, the sequences are the same:

public bool SequenceEquals(IEnumerable<T> second)

{

var firstIter = sequence.GetEnumerator();

var secondIter = second.GetEnumerator();

while ((firstIter?.MoveNext() == true) && secondIter.MoveNext())

{

if ((firstIter.Current is not null) && !firstIter.Current.Equals(secondIter.Current))

{

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

This method shows a second LINQ idiom: terminal methods. They take a sequence as input (or in this case, two sequences) and return a single scalar value. When you use terminal methods, they're always the final method in a chain of methods for a LINQ query.

You can see this in action when you use it to determine when the deck is back in its original order. Put the shuffle code inside a loop, and stop when the sequence is back in its original order by applying the SequenceEquals() method. You can see it would always be the final method in any query because it returns a single value instead of a sequence:

var startingDeck = from s in Suits()

from r in Ranks()

select (Suit: s, Rank: r);

// Display each card generated and placed in startingDeck in the console

foreach (var card in startingDeck)

{

Console.WriteLine(card);

}

var top = startingDeck.Take(26);

var bottom = startingDeck.Skip(26);

var shuffledDeck = top.InterleaveSequenceWith(bottom);

var times = 0;

// Re-use the shuffle variable from earlier, or you can make a new one

shuffledDeck = startingDeck;

do

{

shuffledDeck = shuffledDeck.Take(26).InterleaveSequenceWith(shuffledDeck.Skip(26));

foreach (var card in shuffledDeck)

{

Console.WriteLine(card);

}

Console.WriteLine();

times++;

} while (!startingDeck.SequenceEquals(shuffledDeck));

Console.WriteLine(times);

Run the code you built so far and notice how the deck rearranges on each shuffle. After 8 shuffles (iterations of the do-while loop), the deck returns to the original configuration it was in when you first created it from the starting LINQ query.

Optimizations

The sample you built so far executes an out shuffle, where the top and bottom cards stay the same on each run. Let's make one change: use an in shuffle instead, where all 52 cards change position. For an in shuffle, you interleave the deck so that the first card in the bottom half becomes the first card in the deck. That means the last card in the top half becomes the bottom card. This change requires one line of code. Update the current shuffle query by switching the positions of Take and Skip. This change switches the order of the top and bottom halves of the deck:

shuffledDeck = shuffledDeck.Skip(26).InterleaveSequenceWith(shuffledDeck.Take(26));

Run the program again, and you see that it takes 52 iterations for the deck to reorder itself. You also notice some serious performance degradation as the program continues to run.

There are several reasons for this performance drop. You can tackle one of the major causes: inefficient use of lazy evaluation.

Lazy evaluation states that the evaluation of a statement isn't performed until its value is needed. LINQ queries are statements that are evaluated lazily. The sequences are generated only as the elements are requested. Usually, that's a major benefit of LINQ. However, in a program like this one, lazy evaluation causes exponential growth in execution time.

Remember that you generated the original deck using a LINQ query. Each shuffle is generated by performing three LINQ queries on the previous deck. All these queries are performed lazily. That also means they're performed again each time the sequence is requested. By the time you get to the 52nd iteration, you're regenerating the original deck many times. Write a log to demonstrate this behavior. Once you gather data, you can improve performance.

In your Extensions.cs file, type in or copy the method in the following code sample. This extension method creates a new file called debug.log within your project directory and records what query is currently being executed to the log file. Append this extension method to any query to mark that the query executed.

public IEnumerable<T> LogQuery(string tag)

{

// File.AppendText creates a new file if the file doesn't exist.

using (var writer = File.AppendText("debug.log"))

{

writer.WriteLine($"Executing Query {tag}");

}

return sequence;

}

Next, instrument the definition of each query with a log message:

var startingDeck = (from s in Suits().LogQuery("Suit Generation")

from r in Ranks().LogQuery("Rank Generation")

select (Suit: s, Rank: r)).LogQuery("Starting Deck");

foreach (var c in startingDeck)

{

Console.WriteLine(c);

}

Console.WriteLine();

var times = 0;

var shuffle = startingDeck;

do

{

// Out shuffle

/*

shuffle = shuffle.Take(26)

.LogQuery("Top Half")

.InterleaveSequenceWith(shuffle.Skip(26)

.LogQuery("Bottom Half"))

.LogQuery("Shuffle");

*/

// In shuffle

shuffle = shuffle.Skip(26).LogQuery("Bottom Half")

.InterleaveSequenceWith(shuffle.Take(26).LogQuery("Top Half"))

.LogQuery("Shuffle");

foreach (var c in shuffle)

{

Console.WriteLine(c);

}

times++;

Console.WriteLine(times);

} while (!startingDeck.SequenceEquals(shuffle));

Console.WriteLine(times);

Notice that you don't log every time you access a query. You log only when you create the original query. The program still takes a long time to run, but now you can see why. If you run out of patience running the in shuffle with logging turned on, switch back to the out shuffle. You still see the lazy evaluation effects. In one run, it executes 2,592 queries, including the value and suit generation.

You can improve the performance of the code to reduce the number of executions you make. A simple fix is to cache the results of the original LINQ query that constructs the deck of cards. Currently, you're executing the queries again and again every time the do-while loop goes through an iteration, reconstructing the deck of cards and reshuffling it every time. To cache the deck of cards, apply the LINQ methods ToArray and ToList. When you append them to the queries, they perform the same actions you told them to, but now they store the results in an array or a list, depending on which method you choose to call. Append the LINQ method ToArray to both queries and run the program again:

var startingDeck = (from s in suits().LogQuery("Suit Generation")

from r in ranks().LogQuery("Value Generation")

select new { Suit = s, Rank = r })

.LogQuery("Starting Deck")

.ToArray();

foreach (var c in startingDeck)

{

Console.WriteLine(c);

}

Console.WriteLine();

var times = 0;

var shuffle = startingDeck;

do

{

/*

shuffle = shuffle.Take(26)

.LogQuery("Top Half")

.InterleaveSequenceWith(shuffle.Skip(26).LogQuery("Bottom Half"))

.LogQuery("Shuffle")

.ToArray();

*/

shuffle = shuffle.Skip(26)

.LogQuery("Bottom Half")

.InterleaveSequenceWith(shuffle.Take(26).LogQuery("Top Half"))

.LogQuery("Shuffle")

.ToArray();

foreach (var c in shuffle)

{

Console.WriteLine(c);

}

times++;

Console.WriteLine(times);

} while (!startingDeck.SequenceEquals(shuffle));

Console.WriteLine(times);

Now the out shuffle is down to 30 queries. Run again with the in shuffle and you see similar improvements: it now executes 162 queries.

This example is designed to highlight the use cases where lazy evaluation can cause performance difficulties. While it's important to see where lazy evaluation can impact code performance, it's equally important to understand that not all queries should run eagerly. The performance hit you incur without using ToArray is because each new arrangement of the deck of cards is built from the previous arrangement. Using lazy evaluation means each new deck configuration is built from the original deck, even executing the code that built the startingDeck. That causes a large amount of extra work.

In practice, some algorithms run well using eager evaluation, and others run well using lazy evaluation. For daily usage, lazy evaluation is usually a better choice when the data source is a separate process, like a database engine. For databases, lazy evaluation allows more complex queries to execute only one round trip to the database process and back to the rest of your code. LINQ is flexible whether you choose to use lazy or eager evaluation, so measure your processes and pick whichever evaluation gives you the best performance.

Conclusion

In this project, you covered:

- Using LINQ queries to aggregate data into a meaningful sequence.

- Writing extension methods to add custom functionality to LINQ queries.

- Locating areas in code where LINQ queries might run into performance issues like degraded speed.

- Lazy and eager evaluation in LINQ queries and the implications they might have on query performance.

Aside from LINQ, you learned about a technique magicians use for card tricks. Magicians use the faro shuffle because they can control where every card moves in the deck. Now that you know, don't spoil it for everyone else!

For more information on LINQ, see: