Testability and Entity Framework 4.0

Scott Allen

Published: May 2010

Introduction

This white paper describes and demonstrates how to write testable code with the ADO.NET Entity Framework 4.0 and Visual Studio 2010. This paper does not try to focus on a specific testing methodology, like test-driven design (TDD) or behavior-driven design (BDD). Instead this paper will focus on how to write code that uses the ADO.NET Entity Framework yet remains easy to isolate and test in an automated fashion. We’ll look at common design patterns that facilitate testing in data access scenarios and see how to apply those patterns when using the framework. We’ll also look at specific features of the framework to see how those features can work in testable code.

What Is Testable Code?

The ability to verify a piece of software using automated unit tests offers many desirable benefits. Everyone knows that good tests will reduce the number of software defects in an application and increase the application’s quality - but having unit tests in place goes far beyond just finding bugs.

A good unit test suite allows a development team to save time and remain in control of the software they create. A team can make changes to existing code, refactor, redesign, and restructure software to meet new requirements, and add new components into an application all while knowing the test suite can verify the application’s behavior. Unit tests are part of a quick feedback cycle to facilitate change and preserve the maintainability of software as complexity increases.

Unit testing comes with a price, however. A team has to invest the time to create and maintain unit tests. The amount of effort required to create these tests is directly related to the testability of the underlying software. How easy is the software to test? A team designing software with testability in mind will create effective tests faster than the team working with un-testable software.

Microsoft designed the ADO.NET Entity Framework 4.0 (EF4) with testability in mind. This doesn’t mean developers will be writing unit tests against framework code itself. Instead, the testability goals for EF4 make it easy to create testable code that builds on top of the framework. Before we look at specific examples, it’s worthwhile to understand the qualities of testable code.

The Qualities of Testable Code

Code that is easy to test will always exhibit at least two traits. First, testable code is easy to observe. Given some set of inputs, it should be easy to observe the output of the code. For example, testing the following method is easy because the method directly returns the result of a calculation.

public int Add(int x, int y) {

return x + y;

}

Testing a method is difficult if the method writes the computed value into a network socket, a database table, or a file like the following code. The test has to perform additional work to retrieve the value.

public void AddAndSaveToFile(int x, int y) {

var results = string.Format("The answer is {0}", x + y);

File.WriteAllText("results.txt", results);

}

Secondly, testable code is easy to isolate. Let’s use the following pseudo-code as a bad example of testable code.

public int ComputePolicyValue(InsurancePolicy policy) {

using (var connection = new SqlConnection("dbConnection"))

using (var command = new SqlCommand(query, connection)) {

// business calculations omitted ...

if (totalValue > notificationThreshold) {

var message = new MailMessage();

message.Subject = "Warning!";

var client = new SmtpClient();

client.Send(message);

}

}

return totalValue;

}

The method is easy to observe – we can pass in an insurance policy and verify the return value matches an expected result. However, to test the method we’ll need to have a database installed with the correct schema, and configure the SMTP server in case the method tries to send an email.

The unit test only wants to verify the calculation logic inside the method, but the test might fail because the email server is offline, or because the database server moved. Both of these failures are unrelated to the behavior the test wants to verify. The behavior is difficult to isolate.

Software developers who strive to write testable code often strive to maintain a separation of concerns in the code they write. The above method should focus on the business calculations and delegate the database and email implementation details to other components. Robert C. Martin calls this the Single Responsibility Principle. An object should encapsulate a single, narrow responsibility, like calculating the value of a policy. All other database and notification work should be the responsibility of some other object. Code written in this fashion is easier to isolate because it is focused on a single task.

In .NET we have the abstractions we need to follow the Single Responsibility Principle and achieve isolation. We can use interface definitions and force the code to use the interface abstraction instead of a concrete type. Later in this paper we’ll see how a method like the bad example presented above can work with interfaces that look like they will talk to the database. At test time, however, we can substitute a dummy implementation that doesn’t talk to the database but instead holds data in memory. This dummy implementation will isolate the code from unrelated problems in the data access code or database configuration.

There are additional benefits to isolation. The business calculation in the last method should only take a few milliseconds to execute, but the test itself might run for several seconds as the code hops around the network and talks to various servers. Unit tests should run fast to facilitate small changes. Unit tests should also be repeatable and not fail because a component unrelated to the test has a problem. Writing code that is easy to observe and to isolate means developers will have an easier time writing tests for the code, spend less time waiting for tests to execute, and more importantly, spend less time tracking down bugs that do not exist.

Hopefully you can appreciate the benefits of testing and understand the qualities that testable code exhibits. We are about to address how to write code that works with EF4 to save data into a database while remaining observable and easy to isolate, but first we’ll narrow our focus to discuss testable designs for data access.

Design Patterns for Data Persistence

Both of the bad examples presented earlier had too many responsibilities. The first bad example had to perform a calculation and write to a file. The second bad example had to read data from a database and perform a business calculation and send email. By designing smaller methods that separate concerns and delegate responsibility to other components you’ll make great strides towards writing testable code. The goal is to build functionality by composing actions from small and focused abstractions.

When it comes to data persistence the small and focused abstractions we are looking for are so common they’ve been documented as design patterns. Martin Fowler’s book Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture was the first work to describe these patterns in print. We’ll provide a brief description of these patterns in the following sections before we show how these ADO.NET Entity Framework implements and works with these patterns.

The Repository Pattern

Fowler says a repository “mediates between the domain and data mapping layers using a collection-like interface for accessing domain objects”. The goal of the repository pattern is to isolate code from the minutiae of data access, and as we saw earlier isolation is a required trait for testability.

The key to the isolation is how the repository exposes objects using a collection-like interface. The logic you write to use the repository has no idea how the repository will materialize the objects you request. The repository might talk to a database, or it might just return objects from an in-memory collection. All your code needs to know is that the repository appears to maintain the collection, and you can retrieve, add, and delete objects from the collection.

In existing .NET applications a concrete repository often inherits from a generic interface like the following:

public interface IRepository<T> {

IEnumerable<T> FindAll();

IEnumerable<T> FindBy(Expression<Func\<T, bool>> predicate);

T FindById(int id);

void Add(T newEntity);

void Remove(T entity);

}

We’ll make a few changes to the interface definition when we provide an implementation for EF4, but the basic concept remains the same. Code can use a concrete repository implementing this interface to retrieve an entity by its primary key value, to retrieve a collection of entities based on the evaluation of a predicate, or simply retrieve all available entities. The code can also add and remove entities through the repository interface.

Given an IRepository of Employee objects, code can perform the following operations.

var employeesNamedScott =

repository

.FindBy(e => e.Name == "Scott")

.OrderBy(e => e.HireDate);

var firstEmployee = repository.FindById(1);

var newEmployee = new Employee() {/*... */};

repository.Add(newEmployee);

Since the code is using an interface (IRepository of Employee), we can provide the code with different implementations of the interface. One implementation might be an implementation backed by EF4 and persisting objects into a Microsoft SQL Server database. A different implementation (one we use during testing) might be backed by an in-memory List of Employee objects. The interface will help to achieve isolation in the code.

Notice the IRepository<T> interface does not expose a Save operation. How do we update existing objects? You might come across IRepository definitions that do include the Save operation, and implementations of these repositories will need to immediately persist an object into the database. However, in many applications we don’t want to persist objects individually. Instead, we want to bring objects to life, perhaps from different repositories, modify those objects as part of a business activity, and then persist all the objects as part of a single, atomic operation. Fortunately, there is a pattern to allow this type of behavior.

The Unit of Work Pattern

Fowler says a unit of work will “maintain a list of objects affected by a business transaction and coordinates the writing out of changes and the resolution of concurrency problems”. It is the responsibility of the unit of work to track changes to the objects we bring to life from a repository and persist any changes we’ve made to the objects when we tell the unit of work to commit the changes. It’s also the responsibility of the unit of work to take the new objects we’ve added to all repositories and insert the objects into a database, and also mange deletion.

If you’ve ever done any work with ADO.NET DataSets then you’ll already be familiar with the unit of work pattern. ADO.NET DataSets had the ability to track our updates, deletions, and insertion of DataRow objects and could (with the help of a TableAdapter) reconcile all our changes to a database. However, DataSet objects model a disconnected subset of the underlying database. The unit of work pattern exhibits the same behavior, but works with business objects and domain objects that are isolated from data access code and unaware of the database.

An abstraction to model the unit of work in .NET code might look like the following:

public interface IUnitOfWork {

IRepository<Employee> Employees { get; }

IRepository<Order> Orders { get; }

IRepository<Customer> Customers { get; }

void Commit();

}

By exposing repository references from the unit of work we can ensure a single unit of work object has the ability to track all entities materialized during a business transaction. The implementation of the Commit method for a real unit of work is where all the magic happens to reconcile in-memory changes with the database.

Given an IUnitOfWork reference, code can make changes to business objects retrieved from one or more repositories and save all the changes using the atomic Commit operation.

var firstEmployee = unitofWork.Employees.FindById(1);

var firstCustomer = unitofWork.Customers.FindById(1);

firstEmployee.Name = "Alex";

firstCustomer.Name = "Christopher";

unitofWork.Commit();

The Lazy Load Pattern

Fowler uses the name lazy load to describe “an object that doesn’t contain all of the data you need but knows how to get it”. Transparent lazy loading is an important feature to have when writing testable business code and working with a relational database. As an example, consider the following code.

var employee = repository.FindById(id);

// ... and later ...

foreach(var timeCard in employee.TimeCards) {

// .. manipulate the timeCard

}

How is the TimeCards collection populated? There are two possible answers. One answer is that the employee repository, when asked to fetch an employee, issues a query to retrieve both the employee along with the employee’s associated time card information. In relational databases this generally requires a query with a JOIN clause and may result in retrieving more information than an application needs. What if the application never needs to touch the TimeCards property?

A second answer is to load the TimeCards property “on demand”. This lazy loading is implicit and transparent to the business logic because the code does not invoke special APIs to retrieve time card information. The code assumes the time card information is present when needed. There is some magic involved with lazy loading that generally involves runtime interception of method invocations. The intercepting code is responsible for talking to the database and retrieving time card information while leaving the business logic free to be business logic. This lazy load magic allows the business code to isolate itself from data retrieval operations and results in more testable code.

The drawback to a lazy load is that when an application does need the time card information the code will execute an additional query. This isn’t a concern for many applications, but for performance sensitive applications or applications looping through a number of employee objects and executing a query to retrieve time cards during each iteration of the loop (a problem often referred to as the N+1 query problem), lazy loading is a drag. In these scenarios an application might want to eagerly load time card information in the most efficient manner possible.

Fortunately, we’ll see how EF4 supports both implicit lazy loads and efficient eager loads as we move into the next section and implement these patterns.

Implementing Patterns with the Entity Framework

The good news is that all of the design patterns we described in the last section are straightforward to implement with EF4. To demonstrate we are going to use a simple ASP.NET MVC application to edit and display Employees and their associated time card information. We’ll start by using the following “plain old CLR objects” (POCOs).

public class Employee {

public int Id { get; set; }

public string Name { get; set; }

public DateTime HireDate { get; set; }

public ICollection<TimeCard> TimeCards { get; set; }

}

public class TimeCard {

public int Id { get; set; }

public int Hours { get; set; }

public DateTime EffectiveDate { get; set; }

}

These class definitions will change slightly as we explore different approaches and features of EF4, but the intent is to keep these classes as persistence ignorant (PI) as possible. A PI object doesn’t know how, or even if, the state it holds lives inside a database. PI and POCOs go hand in hand with testable software. Objects using a POCO approach are less constrained, more flexible, and easier to test because they can operate without a database present.

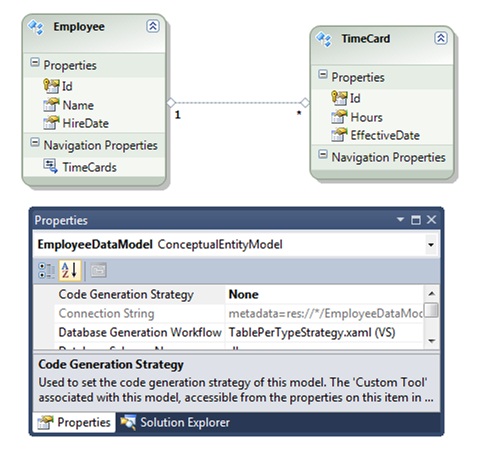

With the POCOs in place we can create an Entity Data Model (EDM) in Visual Studio (see figure 1). We will not use the EDM to generate code for our entities. Instead, we want to use the entities we lovingly craft by hand. We will only use the EDM to generate our database schema and provide the metadata EF4 needs to map objects into the database.

Figure 1

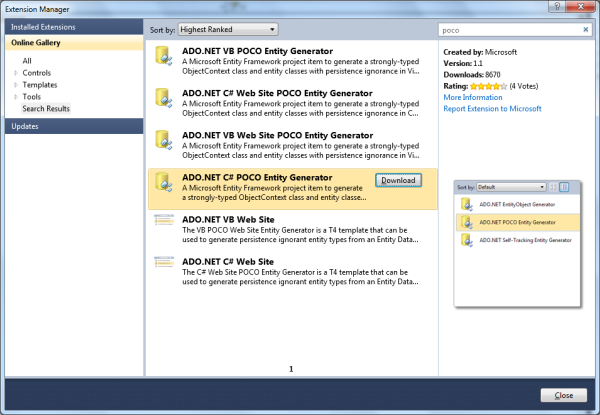

Note: if you want to develop the EDM model first, it is possible to generate clean, POCO code from the EDM. You can do this with a Visual Studio 2010 extension provided by the Data Programmability team. To download the extension, launch the Extension Manager from the Tools menu in Visual Studio and search the online gallery of templates for “POCO” (See figure 2). There are several POCO templates available for EF. For more information on using the template, see “ Walkthrough: POCO Template for the Entity Framework”.

Figure 2

From this POCO starting point we will explore two different approaches to testable code. The first approach I call the EF approach because it leverages abstractions from the Entity Framework API to implement units of work and repositories. In the second approach we will create our own custom repository abstractions and then see the advantages and disadvantages of each approach. We’ll start by exploring the EF approach.

An EF Centric Implementation

Consider the following controller action from an ASP.NET MVC project. The action retrieves an Employee object and returns a result to display a detailed view of the employee.

public ViewResult Details(int id) {

var employee = _unitOfWork.Employees

.Single(e => e.Id == id);

return View(employee);

}

Is the code testable? There are at least two tests we’d need to verify the action’s behavior. First, we’d like to verify the action returns the correct view – an easy test. We’d also want to write a test to verify the action retrieves the correct employee, and we’d like to do this without executing code to query the database. Remember we want to isolate the code under test. Isolation will ensure the test doesn’t fail because of a bug in the data access code or database configuration. If the test fails, we will know we have a bug in the controller logic, and not in some lower level system component.

To achieve isolation we’ll need some abstractions like the interfaces we presented earlier for repositories and units of work. Remember the repository pattern is designed to mediate between domain objects and the data mapping layer. In this scenario EF4 is the data mapping layer, and already provides a repository-like abstraction named IObjectSet<T> (from the System.Data.Objects namespace). The interface definition looks like the following.

public interface IObjectSet<TEntity> :

IQueryable<TEntity>,

IEnumerable<TEntity>,

IQueryable,

IEnumerable

where TEntity : class

{

void AddObject(TEntity entity);

void Attach(TEntity entity);

void DeleteObject(TEntity entity);

void Detach(TEntity entity);

}

IObjectSet<T> meets the requirements for a repository because it resembles a collection of objects (via IEnumerable<T>) and provides methods to add and remove objects from the simulated collection. The Attach and Detach methods expose additional capabilities of the EF4 API. To use IObjectSet<T> as the interface for repositories we need a unit of work abstraction to bind repositories together.

public interface IUnitOfWork {

IObjectSet<Employee> Employees { get; }

IObjectSet<TimeCard> TimeCards { get; }

void Commit();

}

One concrete implementation of this interface will talk to SQL Server and is easy to create using the ObjectContext class from EF4. The ObjectContext class is the real unit of work in the EF4 API.

public class SqlUnitOfWork : IUnitOfWork {

public SqlUnitOfWork() {

var connectionString =

ConfigurationManager

.ConnectionStrings[ConnectionStringName]

.ConnectionString;

_context = new ObjectContext(connectionString);

}

public IObjectSet<Employee> Employees {

get { return _context.CreateObjectSet<Employee>(); }

}

public IObjectSet<TimeCard> TimeCards {

get { return _context.CreateObjectSet<TimeCard>(); }

}

public void Commit() {

_context.SaveChanges();

}

readonly ObjectContext _context;

const string ConnectionStringName = "EmployeeDataModelContainer";

}

Bringing an IObjectSet<T> to life is as easy as invoking the CreateObjectSet method of the ObjectContext object. Behind the scenes the framework will use the metadata we provided in the EDM to produce a concrete ObjectSet<T>. We’ll stick with returning the IObjectSet<T> interface because it will help preserve testability in client code.

This concrete implementation is useful in production, but we need to focus on how we’ll use our IUnitOfWork abstraction to facilitate testing.

The Test Doubles

To isolate the controller action we’ll need the ability to switch between the real unit of work (backed by an ObjectContext) and a test double or “fake” unit of work (performing in-memory operations). The common approach to perform this type of switching is to not let the MVC controller instantiate a unit of work, but instead pass the unit of work into the controller as a constructor parameter.

class EmployeeController : Controller {

publicEmployeeController(IUnitOfWork unitOfWork) {

_unitOfWork = unitOfWork;

}

...

}

The above code is an example of dependency injection. We don’t allow the controller to create it’s dependency (the unit of work) but inject the dependency into the controller. In an MVC project it is common to use a custom controller factory in combination with an inversion of control (IoC) container to automate dependency injection. These topics are beyond the scope of this article, but you can read more by following the references at the end of this article.

A fake unit of work implementation that we can use for testing might look like the following.

public class InMemoryUnitOfWork : IUnitOfWork {

public InMemoryUnitOfWork() {

Committed = false;

}

public IObjectSet<Employee> Employees {

get;

set;

}

public IObjectSet<TimeCard> TimeCards {

get;

set;

}

public bool Committed { get; set; }

public void Commit() {

Committed = true;

}

}

Notice the fake unit of work exposes a Commited property. It’s sometimes useful to add features to a fake class that facilitate testing. In this case it is easy to observe if code commits a unit of work by checking the Commited property.

We’ll also need a fake IObjectSet<T> to hold Employee and TimeCard objects in memory. We can provide a single implementation using generics.

public class InMemoryObjectSet<T> : IObjectSet<T> where T : class

public InMemoryObjectSet()

: this(Enumerable.Empty<T>()) {

}

public InMemoryObjectSet(IEnumerable<T> entities) {

_set = new HashSet<T>();

foreach (var entity in entities) {

_set.Add(entity);

}

_queryableSet = _set.AsQueryable();

}

public void AddObject(T entity) {

_set.Add(entity);

}

public void Attach(T entity) {

_set.Add(entity);

}

public void DeleteObject(T entity) {

_set.Remove(entity);

}

public void Detach(T entity) {

_set.Remove(entity);

}

public Type ElementType {

get { return _queryableSet.ElementType; }

}

public Expression Expression {

get { return _queryableSet.Expression; }

}

public IQueryProvider Provider {

get { return _queryableSet.Provider; }

}

public IEnumerator<T> GetEnumerator() {

return _set.GetEnumerator();

}

IEnumerator IEnumerable.GetEnumerator() {

return GetEnumerator();

}

readonly HashSet<T> _set;

readonly IQueryable<T> _queryableSet;

}

This test double delegates most of its work to an underlying HashSet<T> object. Note that IObjectSet<T> requires a generic constraint enforcing T as a class (a reference type), and also forces us to implement IQueryable<T>. It is easy to make an in-memory collection appear as an IQueryable<T> using the standard LINQ operator AsQueryable.

The Tests

Traditional unit tests will use a single test class to hold all of the tests for all of the actions in a single MVC controller. We can write these tests, or any type of unit test, using the in memory fakes we’ve built. However, for this article we will avoid the monolithic test class approach and instead group our tests to focus on a specific piece of functionality. For example, “create new employee” might be the functionality we want to test, so we will use a single test class to verify the single controller action responsible for creating a new employee.

There is some common setup code we need for all these fine grained test classes. For example, we always need to create our in-memory repositories and fake unit of work. We also need an instance of the employee controller with the fake unit of work injected. We’ll share this common setup code across test classes by using a base class.

public class EmployeeControllerTestBase {

public EmployeeControllerTestBase() {

_employeeData = EmployeeObjectMother.CreateEmployees()

.ToList();

_repository = new InMemoryObjectSet<Employee>(_employeeData);

_unitOfWork = new InMemoryUnitOfWork();

_unitOfWork.Employees = _repository;

_controller = new EmployeeController(_unitOfWork);

}

protected IList<Employee> _employeeData;

protected EmployeeController _controller;

protected InMemoryObjectSet<Employee> _repository;

protected InMemoryUnitOfWork _unitOfWork;

}

The “object mother” we use in the base class is one common pattern for creating test data. An object mother contains factory methods to instantiate test entities for use across multiple test fixtures.

public static class EmployeeObjectMother {

public static IEnumerable<Employee> CreateEmployees() {

yield return new Employee() {

Id = 1, Name = "Scott", HireDate=new DateTime(2002, 1, 1)

};

yield return new Employee() {

Id = 2, Name = "Poonam", HireDate=new DateTime(2001, 1, 1)

};

yield return new Employee() {

Id = 3, Name = "Simon", HireDate=new DateTime(2008, 1, 1)

};

}

// ... more fake data for different scenarios

}

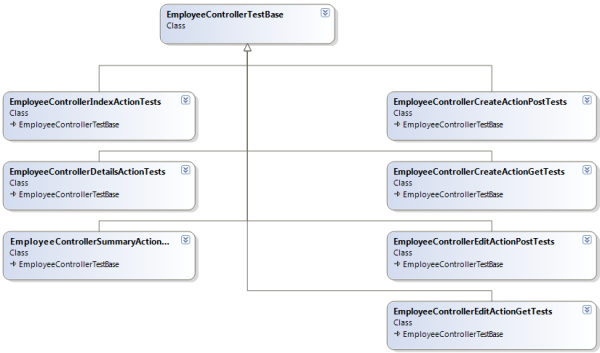

We can use the EmployeeControllerTestBase as the base class for a number of test fixtures (see figure 3). Each test fixture will test a specific controller action. For example, one test fixture will focus on testing the Create action used during an HTTP GET request (to display the view for creating an employee), and a different fixture will focus on the Create action used in an HTTP POST request (to take information submitted by the user to create an employee). Each derived class is only responsible for the setup needed in its specific context, and to provide the assertions needed to verify the outcomes for its specific test context.

Figure 3

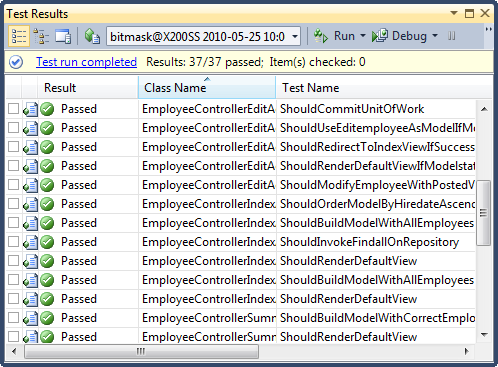

The naming convention and test style presented here isn’t required for testable code – it’s just one approach. Figure 4 shows the tests running in the Jet Brains Resharper test runner plugin for Visual Studio 2010.

Figure 4

With a base class to handle the shared setup code, the unit tests for each controller action are small and easy to write. The tests will execute quickly (since we are performing in-memory operations), and shouldn’t fail because of unrelated infrastructure or environmental concerns (because we’ve isolated the unit under test).

[TestClass]

public class EmployeeControllerCreateActionPostTests

: EmployeeControllerTestBase {

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldAddNewEmployeeToRepository() {

_controller.Create(_newEmployee);

Assert.IsTrue(_repository.Contains(_newEmployee));

}

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldCommitUnitOfWork() {

_controller.Create(_newEmployee);

Assert.IsTrue(_unitOfWork.Committed);

}

// ... more tests

Employee _newEmployee = new Employee() {

Name = "NEW EMPLOYEE",

HireDate = new System.DateTime(2010, 1, 1)

};

}

In these tests, the base class does most of the setup work. Remember the base class constructor creates the in-memory repository, a fake unit of work, and an instance of the EmployeeController class. The test class derives from this base class and focuses on the specifics of testing the Create method. In this case the specifics boil down to the “arrange, act, and assert” steps you’ll see in any unit testing procedure:

- Create a newEmployee object to simulate incoming data.

- Invoke the Create action of the EmployeeController and pass in the newEmployee.

- Verify the Create action produces the expected results (the employee appears in the repository).

What we’ve built allows us to test any of the EmployeeController actions. For example, when we write tests for the Index action of the Employee controller we can inherit from the test base class to establish the same base setup for our tests. Again the base class will create the in-memory repository, the fake unit of work, and an instance of the EmployeeController. The tests for the Index action only need to focus on invoking the Index action and testing the qualities of the model the action returns.

[TestClass]

public class EmployeeControllerIndexActionTests

: EmployeeControllerTestBase {

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldBuildModelWithAllEmployees() {

var result = _controller.Index();

var model = result.ViewData.Model

as IEnumerable<Employee>;

Assert.IsTrue(model.Count() == _employeeData.Count);

}

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldOrderModelByHiredateAscending() {

var result = _controller.Index();

var model = result.ViewData.Model

as IEnumerable<Employee>;

Assert.IsTrue(model.SequenceEqual(

_employeeData.OrderBy(e => e.HireDate)));

}

// ...

}

The tests we are creating with in-memory fakes are oriented towards testing the state of the software. For example, when testing the Create action we want to inspect the state of the repository after the create action executes – does the repository hold the new employee?

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldAddNewEmployeeToRepository() {

_controller.Create(_newEmployee);

Assert.IsTrue(_repository.Contains(_newEmployee));

}

Later we’ll look at interaction based testing. Interaction based testing will ask if the code under test invoked the proper methods on our objects and passed the correct parameters. For now we’ll move on the cover another design pattern – the lazy load.

Eager Loading and Lazy Loading

At some point in the ASP.NET MVC web application we might wish to display an employee’s information and include the employee’s associated time cards. For example, we might have a time card summary display that shows the employee’s name and the total number of time cards in the system. There are several approaches we can take to implement this feature.

Projection

One easy approach to create the summary is to construct a model dedicated to the information we want to display in the view. In this scenario the model might look like the following.

public class EmployeeSummaryViewModel {

public string Name { get; set; }

public int TotalTimeCards { get; set; }

}

Note that the EmployeeSummaryViewModel is not an entity – in other words it is not something we want to persist in the database. We are only going to use this class to shuffle data into the view in a strongly typed manner. The view model is like a data transfer object (DTO) because it contains no behavior (no methods) – only properties. The properties will hold the data we need to move. It is easy to instantiate this view model using LINQ’s standard projection operator – the Select operator.

public ViewResult Summary(int id) {

var model = _unitOfWork.Employees

.Where(e => e.Id == id)

.Select(e => new EmployeeSummaryViewModel

{

Name = e.Name,

TotalTimeCards = e.TimeCards.Count()

})

.Single();

return View(model);

}

There are two notable features to the above code. First – the code is easy to test because it is still easy to observe and isolate. The Select operator works just as well against our in-memory fakes as it does against the real unit of work.

[TestClass]

public class EmployeeControllerSummaryActionTests

: EmployeeControllerTestBase {

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldBuildModelWithCorrectEmployeeSummary() {

var id = 1;

var result = _controller.Summary(id);

var model = result.ViewData.Model as EmployeeSummaryViewModel;

Assert.IsTrue(model.TotalTimeCards == 3);

}

// ...

}

The second notable feature is how the code allows EF4 to generate a single, efficient query to assemble employee and time card information together. We’ve loaded employee information and time card information into the same object without using any special APIs. The code merely expressed the information it requires using standard LINQ operators that work against in-memory data sources as well as remote data sources. EF4 was able to translate the expression trees generated by the LINQ query and C# compiler into a single and efficient T-SQL query.

SELECT

[Limit1].[Id] AS [Id],

[Limit1].[Name] AS [Name],

[Limit1].[C1] AS [C1]

FROM (SELECT TOP (2)

[Project1].[Id] AS [Id],

[Project1].[Name] AS [Name],

[Project1].[C1] AS [C1]

FROM (SELECT

[Extent1].[Id] AS [Id],

[Extent1].[Name] AS [Name],

(SELECT COUNT(1) AS [A1]

FROM [dbo].[TimeCards] AS [Extent2]

WHERE [Extent1].[Id] =

[Extent2].[EmployeeTimeCard_TimeCard_Id]) AS [C1]

FROM [dbo].[Employees] AS [Extent1]

WHERE [Extent1].[Id] = @p__linq__0

) AS [Project1]

) AS [Limit1]

There are other times when we don’t want to work with a view model or DTO object, but with real entities. When we know we need an employee and the employee’s time cards, we can eagerly load the related data in an unobtrusive and efficient manner.

Explicit Eager Loading

When we want to eagerly load related entity information we need some mechanism for business logic (or in this scenario, controller action logic) to express its desire to the repository. The EF4 ObjectQuery<T> class defines an Include method to specify the related objects to retrieve during a query. Remember the EF4 ObjectContext exposes entities via the concrete ObjectSet<T> class which inherits from ObjectQuery<T>. If we were using ObjectSet<T> references in our controller action we could write the following code to specify an eager load of time card information for each employee.

_employees.Include("TimeCards")

.Where(e => e.HireDate.Year > 2009);

However, since we are trying to keep our code testable we are not exposing ObjectSet<T> from outside the real unit of work class. Instead, we rely on the IObjectSet<T> interface which is easier to fake, but IObjectSet<T> does not define an Include method. The beauty of LINQ is that we can create our own Include operator.

public static class QueryableExtensions {

public static IQueryable<T> Include<T>

(this IQueryable<T> sequence, string path) {

var objectQuery = sequence as ObjectQuery<T>;

if(objectQuery != null)

{

return objectQuery.Include(path);

}

return sequence;

}

}

Notice this Include operator is defined as an extension method for IQueryable<T> instead of IObjectSet<T>. This gives us the ability to use the method with a wider range of possible types, including IQueryable<T>, IObjectSet<T>, ObjectQuery<T>, and ObjectSet<T>. In the event the underlying sequence is not a genuine EF4 ObjectQuery<T>, then there is no harm done and the Include operator is a no-op. If the underlying sequence is an ObjectQuery<T> (or derived from ObjectQuery<T>), then EF4 will see our requirement for additional data and formulate the proper SQL query.

With this new operator in place we can explicitly request an eager load of time card information from the repository.

public ViewResult Index() {

var model = _unitOfWork.Employees

.Include("TimeCards")

.OrderBy(e => e.HireDate);

return View(model);

}

When run against a real ObjectContext, the code produces the following single query. The query gathers enough information from the database in one trip to materialize the employee objects and fully populate their TimeCards property.

SELECT

[Project1].[Id] AS [Id],

[Project1].[Name] AS [Name],

[Project1].[HireDate] AS [HireDate],

[Project1].[C1] AS [C1],

[Project1].[Id1] AS [Id1],

[Project1].[Hours] AS [Hours],

[Project1].[EffectiveDate] AS [EffectiveDate],

[Project1].[EmployeeTimeCard_TimeCard_Id] AS [EmployeeTimeCard_TimeCard_Id]

FROM ( SELECT

[Extent1].[Id] AS [Id],

[Extent1].[Name] AS [Name],

[Extent1].[HireDate] AS [HireDate],

[Extent2].[Id] AS [Id1],

[Extent2].[Hours] AS [Hours],

[Extent2].[EffectiveDate] AS [EffectiveDate],

[Extent2].[EmployeeTimeCard_TimeCard_Id] AS

[EmployeeTimeCard_TimeCard_Id],

CASE WHEN ([Extent2].[Id] IS NULL) THEN CAST(NULL AS int)

ELSE 1 END AS [C1]

FROM [dbo].[Employees] AS [Extent1]

LEFT OUTER JOIN [dbo].[TimeCards] AS [Extent2] ON [Extent1].[Id] = [Extent2].[EmployeeTimeCard_TimeCard_Id]

) AS [Project1]

ORDER BY [Project1].[HireDate] ASC,

[Project1].[Id] ASC, [Project1].[C1] ASC

The great news is the code inside the action method remains fully testable. We don’t need to provide any additional features for our fakes to support the Include operator. The bad news is we had to use the Include operator inside of the code we wanted to keep persistence ignorant. This is a prime example of the type of tradeoffs you’ll need to evaluate when building testable code. There are times when you need to let persistence concerns leak outside the repository abstraction to meet performance goals.

The alternative to eager loading is lazy loading. Lazy loading means we do not need our business code to explicitly announce the requirement for associated data. Instead, we use our entities in the application and if additional data is needed Entity Framework will load the data on demand.

Lazy Loading

It’s easy to imagine a scenario where we don’t know what data a piece of business logic will need. We might know the logic needs an employee object, but we may branch into different execution paths where some of those paths require time card information from the employee, and some do not. Scenarios like this are perfect for implicit lazy loading because data magically appears on an as-needed basis.

Lazy loading, also known as deferred loading, does place some requirements on our entity objects. POCOs with true persistence ignorance would not face any requirements from the persistence layer, but true persistence ignorance is practically impossible to achieve. Instead we measure persistence ignorance in relative degrees. It would be unfortunate if we needed to inherit from a persistence oriented base class or use a specialized collection to achieve lazy loading in POCOs. Fortunately, EF4 has a less intrusive solution.

Virtually Undetectable

When using POCO objects, EF4 can dynamically generate runtime proxies for entities. These proxies invisibly wrap the materialized POCOs and provide additional services by intercepting each property get and set operation to perform additional work. One such service is the lazy loading feature we are looking for. Another service is an efficient change tracking mechanism which can record when the program changes the property values of an entity. The list of changes is used by the ObjectContext during the SaveChanges method to persist any modified entities using UPDATE commands.

For these proxies to work, however, they need a way to hook into property get and set operations on an entity, and the proxies achieve this goal by overriding virtual members. Thus, if we want to have implicit lazy loading and efficient change tracking we need to go back to our POCO class definitions and mark properties as virtual.

public class Employee {

public virtual int Id { get; set; }

public virtual string Name { get; set; }

public virtual DateTime HireDate { get; set; }

public virtual ICollection<TimeCard> TimeCards { get; set; }

}

We can still say the Employee entity is mostly persistence ignorant. The only requirement is to use virtual members and this does not impact the testability of the code. We don’t need to derive from any special base class, or even use a special collection dedicated to lazy loading. As the code demonstrates, any class implementing ICollection<T> is available to hold related entities.

There is also one minor change we need to make inside our unit of work. Lazy loading is off by default when working directly with an ObjectContext object. There is a property we can set on the ContextOptions property to enable deferred loading, and we can set this property inside our real unit of work if we want to enable lazy loading everywhere.

public class SqlUnitOfWork : IUnitOfWork {

public SqlUnitOfWork() {

// ...

_context = new ObjectContext(connectionString);

_context.ContextOptions.LazyLoadingEnabled = true;

}

// ...

}

With implicit lazy loading enabled, application code can use an employee and the employee’s associated time cards while remaining blissfully unaware of the work required for EF to load the extra data.

var employee = _unitOfWork.Employees

.Single(e => e.Id == id);

foreach (var card in employee.TimeCards) {

// ...

}

Lazy loading makes the application code easier to write, and with the proxy magic the code remains completely testable. In-memory fakes of the unit of work can simply preload fake entities with associated data when needed during a test.

At this point we’ll turn our attention from building repositories using IObjectSet<T> and look at abstractions to hide all signs of the persistence framework.

Custom Repositories

When we first presented the unit of work design pattern in this article we provided some sample code for what the unit of work might look like. Let’s re-present this original idea using the employee and employee time card scenario we’ve been working with.

public interface IUnitOfWork {

IRepository<Employee> Employees { get; }

IRepository<TimeCard> TimeCards { get; }

void Commit();

}

The primary difference between this unit of work and the unit of work we created in the last section is how this unit of work does not use any abstractions from the EF4 framework (there is no IObjectSet<T>). IObjectSet<T> works well as a repository interface, but the API it exposes might not perfectly align with our application’s needs. In this upcoming approach we will represent repositories using a custom IRepository<T> abstraction.

Many developers who follow test-driven design, behavior-driven design, and domain driven methodologies design prefer the IRepository<T> approach for several reasons. First, the IRepository<T> interface represents an “anti-corruption” layer. As described by Eric Evans in his Domain Driven Design book an anti-corruption layer keeps your domain code away from infrastructure APIs, like a persistence API. Secondly, developers can build methods into the repository that meet the exact needs of an application (as discovered while writing tests). For example, we might frequently need to locate a single entity using an ID value, so we can add a FindById method to the repository interface. Our IRepository<T> definition will look like the following.

public interface IRepository<T>

where T : class, IEntity {

IQueryable<T> FindAll();

IQueryable<T> FindWhere(Expression<Func\<T, bool>> predicate);

T FindById(int id);

void Add(T newEntity);

void Remove(T entity);

}

Notice we’ll drop back to using an IQueryable<T> interface to expose entity collections. IQueryable<T> allows LINQ expression trees to flow into the EF4 provider and give the provider a holistic view of the query. A second option would be to return IEnumerable<T>, which means the EF4 LINQ provider will only see the expressions built inside of the repository. Any grouping, ordering, and projection done outside of the repository will not be composed into the SQL command sent to the database, which can hurt performance. On the other hand, a repository returning only IEnumerable<T> results will never surprise you with a new SQL command. Both approaches will work, and both approaches remain testable.

It’s straightforward to provide a single implementation of the IRepository<T> interface using generics and the EF4 ObjectContext API.

public class SqlRepository<T> : IRepository<T>

where T : class, IEntity {

public SqlRepository(ObjectContext context) {

_objectSet = context.CreateObjectSet<T>();

}

public IQueryable<T> FindAll() {

return _objectSet;

}

public IQueryable<T> FindWhere(

Expression<Func\<T, bool>> predicate) {

return _objectSet.Where(predicate);

}

public T FindById(int id) {

return _objectSet.Single(o => o.Id == id);

}

public void Add(T newEntity) {

_objectSet.AddObject(newEntity);

}

public void Remove(T entity) {

_objectSet.DeleteObject(entity);

}

protected ObjectSet<T> _objectSet;

}

The IRepository<T> approach gives us some additional control over our queries because a client has to invoke a method to get to an entity. Inside the method we could provide additional checks and LINQ operators to enforce application constraints. Notice the interface has two constraints on the generic type parameter. The first constraint is the class cons taint required by ObjectSet<T>, and the second constraint forces our entities to implement IEntity – an abstraction created for the application. The IEntity interface forces entities to have a readable Id property, and we can then use this property in the FindById method. IEntity is defined with the following code.

public interface IEntity {

int Id { get; }

}

IEntity could be considered a small violation of persistence ignorance since our entities are required to implement this interface. Remember persistence ignorance is about tradeoffs, and for many the FindById functionality will outweigh the constraint imposed by the interface. The interface has no impact on testability.

Instantiating a live IRepository<T> requires an EF4 ObjectContext, so a concrete unit of work implementation should manage the instantiation.

public class SqlUnitOfWork : IUnitOfWork {

public SqlUnitOfWork() {

var connectionString =

ConfigurationManager

.ConnectionStrings[ConnectionStringName]

.ConnectionString;

_context = new ObjectContext(connectionString);

_context.ContextOptions.LazyLoadingEnabled = true;

}

public IRepository<Employee> Employees {

get {

if (_employees == null) {

_employees = new SqlRepository<Employee>(_context);

}

return _employees;

}

}

public IRepository<TimeCard> TimeCards {

get {

if (_timeCards == null) {

_timeCards = new SqlRepository<TimeCard>(_context);

}

return _timeCards;

}

}

public void Commit() {

_context.SaveChanges();

}

SqlRepository<Employee> _employees = null;

SqlRepository<TimeCard> _timeCards = null;

readonly ObjectContext _context;

const string ConnectionStringName = "EmployeeDataModelContainer";

}

Using the Custom Repository

Using our custom repository is not significantly different from using the repository based on IObjectSet<T>. Instead of applying LINQ operators directly to a property, we’ll first need to invoke one the repository’s methods to grab an IQueryable<T> reference.

public ViewResult Index() {

var model = _repository.FindAll()

.Include("TimeCards")

.OrderBy(e => e.HireDate);

return View(model);

}

Notice the custom Include operator we implemented previously will work without change. The repository’s FindById method removes duplicated logic from actions trying to retrieve a single entity.

public ViewResult Details(int id) {

var model = _repository.FindById(id);

return View(model);

}

There is no significant difference in the testability of the two approaches we’ve examined. We could provide fake implementations of IRepository<T> by building concrete classes backed by HashSet<Employee> - just like what we did in the last section. However, some developers prefer to use mock objects and mock object frameworks instead of building fakes. We’ll look at using mocks to test our implementation and discuss the differences between mocks and fakes in the next section.

Testing with Mocks

There are different approaches to building what Martin Fowler calls a “test double”. A test double (like a movie stunt double) is an object you build to “stand in” for real, production objects during tests. The in-memory repositories we created are test doubles for the repositories that talk to SQL Server. We’ve seen how to use these test-doubles during the unit tests to isolate code and keep tests running fast.

The test doubles we’ve built have real, working implementations. Behind the scenes each one stores a concrete collection of objects, and they will add and remove objects from this collection as we manipulate the repository during a test. Some developers like to build their test doubles this way – with real code and working implementations. These test doubles are what we call fakes. They have working implementations, but they aren’t real enough for production use. The fake repository doesn’t actually write to the database. The fake SMTP server doesn’t actually send an email message over the network.

Mocks versus Fakes

There is another type of test double known as a mock. While fakes have working implementations, mocks come with no implementation. With the help of a mock object framework we construct these mock objects at run time and use them as test doubles. In this section we’ll be using the open source mocking framework Moq. Here is a simple example of using Moq to dynamically create a test double for an employee repository.

Mock<IRepository<Employee>> mock =

new Mock<IRepository<Employee>>();

IRepository<Employee> repository = mock.Object;

repository.Add(new Employee());

var employee = repository.FindById(1);

We ask Moq for an IRepository<Employee> implementation and it builds one dynamically. We can get to the object implementing IRepository<Employee> by accessing the Object property of the Mock<T> object. It is this inner object we can pass into our controllers, and they won’t know if this is a test double or the real repository. We can invoke methods on the object just like we would invoke methods on an object with a real implementation.

You must be wondering what the mock repository will do when we invoke the Add method. Since there is no implementation behind the mock object, Add does nothing. There is no concrete collection behind the scenes like we had with the fakes we wrote, so the employee is discarded. What about the return value of FindById? In this case the mock object does the only thing it can do, which is return a default value. Since we are returning a reference type (an Employee), the return value is a null value.

Mocks might sound worthless; however, there are two more features of mocks we haven’t talked about. First, the Moq framework records all the calls made on the mock object. Later in the code we can ask Moq if anyone invoked the Add method, or if anyone invoked the FindById method. We’ll see later how we can use this “black box” recording feature in tests.

The second great feature is how we can use Moq to program a mock object with expectations. An expectation tells the mock object how to respond to any given interaction. For example, we can program an expectation into our mock and tell it to return an employee object when someone invokes FindById. The Moq framework uses a Setup API and lambda expressions to program these expectations.

[TestMethod]

public void MockSample() {

Mock<IRepository<Employee>> mock =

new Mock<IRepository<Employee>>();

mock.Setup(m => m.FindById(5))

.Returns(new Employee {Id = 5});

IRepository<Employee> repository = mock.Object;

var employee = repository.FindById(5);

Assert.IsTrue(employee.Id == 5);

}

In this sample we ask Moq to dynamically build a repository, and then we program the repository with an expectation. The expectation tells the mock object to return a new employee object with an Id value of 5 when someone invokes the FindById method passing a value of 5. This test passes, and we didn’t need to build a full implementation to fake IRepository<T>.

Let’s revisit the tests we wrote earlier and rework them to use mocks instead of fakes. Just like before, we’ll use a base class to setup the common pieces of infrastructure we need for all of the controller’s tests.

public class EmployeeControllerTestBase {

public EmployeeControllerTestBase() {

_employeeData = EmployeeObjectMother.CreateEmployees()

.AsQueryable();

_repository = new Mock<IRepository<Employee>>();

_unitOfWork = new Mock<IUnitOfWork>();

_unitOfWork.Setup(u => u.Employees)

.Returns(_repository.Object);

_controller = new EmployeeController(_unitOfWork.Object);

}

protected IQueryable<Employee> _employeeData;

protected Mock<IUnitOfWork> _unitOfWork;

protected EmployeeController _controller;

protected Mock<IRepository<Employee>> _repository;

}

The setup code remains mostly the same. Instead of using fakes, we’ll use Moq to construct mock objects. The base class arranges for the mock unit of work to return a mock repository when code invokes the Employees property. The rest of the mock setup will take place inside the test fixtures dedicated to each specific scenario. For example, the test fixture for the Index action will setup the mock repository to return a list of employees when the action invokes the FindAll method of the mock repository.

[TestClass]

public class EmployeeControllerIndexActionTests

: EmployeeControllerTestBase {

public EmployeeControllerIndexActionTests() {

_repository.Setup(r => r.FindAll())

.Returns(_employeeData);

}

// .. tests

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldBuildModelWithAllEmployees() {

var result = _controller.Index();

var model = result.ViewData.Model

as IEnumerable<Employee>;

Assert.IsTrue(model.Count() == _employeeData.Count());

}

// .. and more tests

}

Except for the expectations, our tests look similar to the tests we had before. However, with the recording ability of a mock framework we can approach testing from a different angle. We’ll look at this new perspective in the next section.

State versus Interaction Testing

There are different techniques you can use to test software with mock objects. One approach is to use state based testing, which is what we have done in this paper so far. State based testing makes assertions about the state of the software. In the last test we invoked an action method on the controller and made an assertion about the model it should build. Here are some other examples of testing state:

- Verify the repository contains the new employee object after Create executes.

- Verify the model holds a list of all employees after Index executes.

- Verify the repository does not contain a given employee after Delete executes.

Another approach you’ll see with mock objects is to verify interactions. While state based testing makes assertions about the state of objects, interaction based testing makes assertions about how objects interact. For example:

- Verify the controller invokes the repository’s Add method when Create executes.

- Verify the controller invokes the repository’s FindAll method when Index executes.

- Verify the controller invokes the unit of work’s Commit method to save changes when Edit executes.

Interaction testing often requires less test data, because we aren’t poking inside of collections and verifying counts. For example, if we know the Details action invokes a repository’s FindById method with the correct value - then the action is probably behaving correctly. We can verify this behavior without setting up any test data to return from FindById.

[TestClass]

public class EmployeeControllerDetailsActionTests

: EmployeeControllerTestBase {

// ...

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldInvokeRepositoryToFindEmployee() {

var result = _controller.Details(_detailsId);

_repository.Verify(r => r.FindById(_detailsId));

}

int _detailsId = 1;

}

The only setup required in the above test fixture is the setup provided by the base class. When we invoke the controller action, Moq will record the interactions with the mock repository. Using the Verify API of Moq, we can ask Moq if the controller invoked FindById with the proper ID value. If the controller did not invoke the method, or invoked the method with an unexpected parameter value, the Verify method will throw an exception and the test will fail.

Here is another example to verify the Create action invokes Commit on the current unit of work.

[TestMethod]

public void ShouldCommitUnitOfWork() {

_controller.Create(_newEmployee);

_unitOfWork.Verify(u => u.Commit());

}

One danger with interaction testing is the tendency to over specify interactions. The ability of the mock object to record and verify every interaction with the mock object doesn’t mean the test should try to verify every interaction. Some interactions are implementation details and you should only verify the interactions required to satisfy the current test.

The choice between mocks or fakes largely depends on the system you are testing and your personal (or team) preferences. Mock objects can drastically reduce the amount of code you need to implement test doubles, but not everyone is comfortable programming expectations and verifying interactions.

Conclusions

In this paper we’ve demonstrated several approaches to creating testable code while using the ADO.NET Entity Framework for data persistence. We can leverage built in abstractions like IObjectSet<T>, or create our own abstractions like IRepository<T>. In both cases, the POCO support in the ADO.NET Entity Framework 4.0 allows the consumers of these abstractions to remain persistent ignorant and highly testable. Additional EF4 features like implicit lazy loading allows business and application service code to work without worrying about the details of a relational data store. Finally, the abstractions we create are easy to mock or fake inside of unit tests, and we can use these test doubles to achieve fast running, highly isolated, and reliable tests.

Additional Resources

- Martin Fowler, Catalog of Patterns from Patterns of Enterprise Application Architecture

- Griffin Caprio, “ Dependency Injection”

- Data Programmability Blog, “ Walkthrough: Test Driven Development with the Entity Framework 4.0”.

- Data Programmability Blog, “ Using Repository and Unit of Work patterns with Entity Framework 4.0”

- Aaron Jensen, “ Introducing Machine Specifications”

- Eric Lee, “ BDD with MSTest”

- Eric Evans, “ Domain Driven Design”

- Martin Fowler, “ Mocks Aren’t Stubs”

- Martin Fowler, “ Test Double”

- Moq

Biography

Scott Allen is a member of the technical staff at Pluralsight and the founder of OdeToCode.com. In 15 years of commercial software development, Scott has worked on solutions for everything from 8-bit embedded devices to highly scalable ASP.NET web applications. You can reach Scott on his blog at OdeToCode, or on Twitter at https://twitter.com/OdeToCode.

Feedback

Coming soon: Throughout 2024 we will be phasing out GitHub Issues as the feedback mechanism for content and replacing it with a new feedback system. For more information see: https://aka.ms/ContentUserFeedback.

Submit and view feedback for