Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

Depending on your data source, information about data types and column names may or may not be provided explicitly. OData REST APIs typically handle this using the $metadata definition, and the Power Query OData.Feed method automatically handles parsing this information and applying it to the data returned from an OData source.

Many REST APIs don't have a way to programmatically determine their schema. In these cases you'll need to include a schema definition in your connector.

Simple hardcoded approach

The simplest approach is to hardcode a schema definition into your connector. This is sufficient for most use cases.

Overall, enforcing a schema on the data returned by your connector has multiple benefits, such as:

- Setting the correct data types.

- Removing columns that don't need to be shown to end users (such as internal IDs or state information).

- Ensuring that each page of data has the same shape by adding any columns that might be missing from a response (REST APIs commonly indicate that fields should be null by omitting them entirely).

Viewing the existing schema with Table.Schema

Consider the following code that returns a simple table from the TripPin OData sample service:

let

url = "https://services.odata.org/TripPinWebApiService/Airlines",

source = Json.Document(Web.Contents(url))[value],

asTable = Table.FromRecords(source)

in

asTable

Note

TripPin is an OData source, so realistically it would make more sense to simply use the OData.Feed function's automatic schema handling. In this example you'll be treating the source as a typical REST API and using Web.Contents to demonstrate the technique of hardcoding a schema by hand.

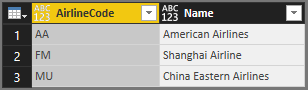

This table is the result:

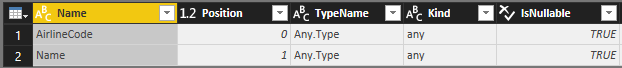

You can use the handy Table.Schema function to check the data type of the columns:

let

url = "https://services.odata.org/TripPinWebApiService/Airlines",

source = Json.Document(Web.Contents(url))[value],

asTable = Table.FromRecords(source)

in

Table.Schema(asTable)

Both AirlineCode and Name are of any type. Table.Schema returns a lot of metadata about the columns in a table, including names, positions, type information, and many advanced properties such as Precision, Scale, and MaxLength. For now you should only concern yourself with the ascribed type (TypeName), primitive type (Kind), and whether the column value might be null (IsNullable).

Defining a simple schema table

Your schema table will be composed of two columns:

| Column | Details |

|---|---|

| Name | The name of the column. This must match the name in the results returned by the service. |

| Type | The M data type you're going to set. This can be a primitive type (text, number, datetime, and so on), or an ascribed type (Int64.Type, Currency.Type, and so on). |

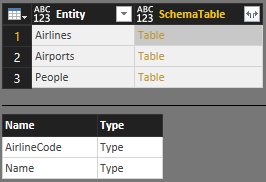

The hardcoded schema table for the Airlines table will set its AirlineCode and Name columns to text and looks like this:

Airlines = #table({"Name", "Type"}, {

{"AirlineCode", type text},

{"Name", type text}

})

As you look to some of the other endpoints, consider the following schema tables:

The Airports table has four fields you'll want to keep (including one of type record):

Airports = #table({"Name", "Type"}, {

{"IcaoCode", type text},

{"Name", type text},

{"IataCode", type text},

{"Location", type record}

})

The People table has seven fields, including lists (Emails, AddressInfo), a nullable column (Gender), and a column with an ascribed type (Concurrency):

People = #table({"Name", "Type"}, {

{"UserName", type text},

{"FirstName", type text},

{"LastName", type text},

{"Emails", type list},

{"AddressInfo", type list},

{"Gender", type nullable text},

{"Concurrency", Int64.Type}

})

You can put all of these tables into a single master schema table SchemaTable:

SchemaTable = #table({"Entity", "SchemaTable"}, {

{"Airlines", Airlines},

{"Airports", Airports},

{"People", People}

})

The SchemaTransformTable helper function

The SchemaTransformTable helper function described below will be used to enforce schemas on your data. It takes the following parameters:

| Parameter | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| table | table | The table of data you'll want to enforce your schema on. |

| schema | table | The schema table to read column info from, with the following type: type table [Name = text, Type = type]. |

| enforceSchema | number | (optional) An enum that controls behavior of the function. The default value ( EnforceSchema.Strict = 1) ensures that the output table will match the schema table that was provided by adding any missing columns, and removing extra columns. The EnforceSchema.IgnoreExtraColumns = 2 option can be used to preserve extra columns in the result. When EnforceSchema.IgnoreMissingColumns = 3 is used, both missing columns and extra columns will be ignored. |

The logic for this function looks something like this:

- Determine if there are any missing columns from the source table.

- Determine if there are any extra columns.

- Ignore structured columns (of type

list,record, andtable), and columns set to typeany. - Use

Table.TransformColumnTypesto set each column type. - Reorder columns based on the order they appear in the schema table.

- Set the type on the table itself using

Value.ReplaceType.

Note

The last step to set the table type will remove the need for the Power Query UI to infer type information when viewing the results in the query editor, which can sometimes result in a double-call to the API.

Putting it all together

In the greater context of a complete extension, the schema handling will take place when a table is returned from the API. Typically this functionality takes place at the lowest level of the paging function (if one exists), with entity information passed through from a navigation table.

Because so much of the implementation of paging and navigation tables is context-specific, the complete example of implementing a hardcoded schema-handling mechanism won't be shown here. This TripPin example demonstrates how an end-to-end solution might look.

Sophisticated approach

The hardcoded implementation discussed above does a good job of making sure that schemas remain consistent for simple JSON repsonses, but it's limited to parsing the first level of the response. Deeply nested data sets would benefit from the following approach, which takes advantage of M Types.

Here is a quick refresh about types in the M language from the Language Specification:

A type value is a value that classifies other values. A value that is classified by a type is said to conform to that type. The M type system consists of the following kinds of types:

- Primitive types, which classify primitive values (

binary,date,datetime,datetimezone,duration,list,logical,null,number,record,text,time,type) and also include a number of abstract types (function,table,any, andnone).- Record types, which classify record values based on field names and value types.

- List types, which classify lists using a single item base type.

- Function types, which classify function values based on the types of their parameters and return values.

- Table types, which classify table values based on column names, column types, and keys.

- Nullable types, which classify the value null in addition to all the values classified by a base type.

- Type types, which classify values that are types.

Using the raw JSON output you get (and/or by looking up the definitions in the service's $metadata), you can define the following record types to represent OData complex types:

LocationType = type [

Address = text,

City = CityType,

Loc = LocType

];

CityType = type [

CountryRegion = text,

Name = text,

Region = text

];

LocType = type [

#"type" = text,

coordinates = {number},

crs = CrsType

];

CrsType = type [

#"type" = text,

properties = record

];

Notice how LocationType references the CityType and LocType to represent its structured columns.

For the top-level entities that you'll want represented as Tables, you can define table types:

AirlinesType = type table [

AirlineCode = text,

Name = text

];

AirportsType = type table [

Name = text,

IataCode = text,

Location = LocationType

];

PeopleType = type table [

UserName = text,

FirstName = text,

LastName = text,

Emails = {text},

AddressInfo = {nullable LocationType},

Gender = nullable text,

Concurrency Int64.Type

];

You can then update your SchemaTable variable (which you can use as a lookup table for entity-to-type mappings) to use these new type definitions:

SchemaTable = #table({"Entity", "Type"}, {

{"Airlines", AirlinesType},

{"Airports", AirportsType},

{"People", PeopleType}

});

You can rely on a common function (Table.ChangeType) to enforce a schema on your data, much like you used SchemaTransformTable in the earlier exercise. Unlike SchemaTransformTable, Table.ChangeType takes an actual M table type as an argument, and will apply your schema recursively for all nested types. Its signature is:

Table.ChangeType = (table, tableType as type) as nullable table => ...

Note

For flexibility, the function can be used on tables as well as lists of records (which is how tables are represented in a JSON document).

You'll then need to update the connector code to change the schema parameter from a table to a type, and add a call to Table.ChangeType. Again, the details for doing so are very implementation-specific and thus not worth going into in detail here. This extended TripPin connector example demonstrates an end-to-end solution implementing this more sophisticated approach to handling schema.