TripPin part 7 - Advanced schema with M types

Note

This content currently references content from a legacy implementation for unit testing in Visual Studio. The content will be updated in the near future to cover the new Power Query SDK test framework.

This multi-part tutorial covers the creation of a new data source extension for Power Query. The tutorial is meant to be done sequentially—each lesson builds on the connector created in previous lessons, incrementally adding new capabilities to your connector.

In this lesson, you will:

- Enforce a table schema using M Types

- Set types for nested records and lists

- Refactor code for reuse and unit testing

In the previous lesson you defined your table schemas using a simple "Schema Table" system. This schema table approach works for many REST APIs/Data Connectors, but services that return complete or deeply nested data sets might benefit from the approach in this tutorial, which leverages the M type system.

This lesson will guide you through the following steps:

- Adding unit tests.

- Defining custom M types.

- Enforcing a schema using types.

- Refactoring common code into separate files.

Adding unit tests

Before you start making use of the advanced schema logic, you'll add a set of unit tests to your connector to reduce the chance of inadvertently breaking something. Unit testing works like this:

- Copy the common code from the UnitTest sample into your

TripPin.query.pqfile. - Add a section declaration to the top of your

TripPin.query.pqfile. - Create a shared record (called

TripPin.UnitTest). - Define a

Factfor each test. - Call

Facts.Summarize()to run all of the tests. - Reference the previous call as the shared value to ensure that it gets evaluated when the project is run in Visual Studio.

section TripPinUnitTests;

shared TripPin.UnitTest =

[

// Put any common variables here if you only want them to be evaluated once

RootTable = TripPin.Contents(),

Airlines = RootTable{[Name="Airlines"]}[Data],

Airports = RootTable{[Name="Airports"]}[Data],

People = RootTable{[Name="People"]}[Data],

// Fact(<Name of the Test>, <Expected Value>, <Actual Value>)

// <Expected Value> and <Actual Value> can be a literal or let statement

facts =

{

Fact("Check that we have three entries in our nav table", 3, Table.RowCount(RootTable)),

Fact("We have Airline data?", true, not Table.IsEmpty(Airlines)),

Fact("We have People data?", true, not Table.IsEmpty(People)),

Fact("We have Airport data?", true, not Table.IsEmpty(Airports)),

Fact("Airlines only has 2 columns", 2, List.Count(Table.ColumnNames(Airlines))),

Fact("Airline table has the right fields",

{"AirlineCode","Name"},

Record.FieldNames(Type.RecordFields(Type.TableRow(Value.Type(Airlines))))

)

},

report = Facts.Summarize(facts)

][report];

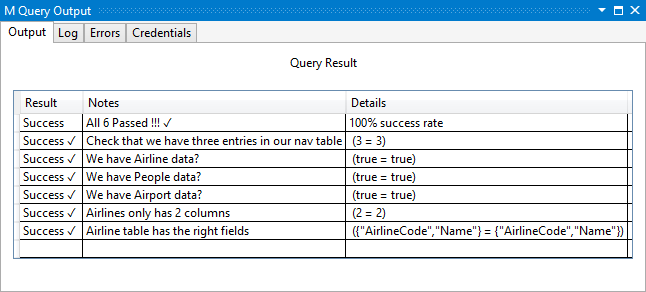

Selecting run on the project will evaluate all of the Facts, and give you a report output that looks like this:

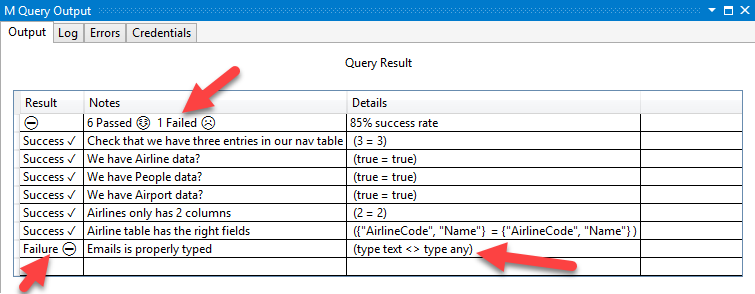

Using some principles from test-driven development, you'll now add a test that currently fails, but will soon be reimplemented and fixed (by the end of this tutorial). Specifically, you'll add a test that checks one of the nested records (Emails) you get back in the People entity.

Fact("Emails is properly typed", type text, Type.ListItem(Value.Type(People{0}[Emails])))

If you run the code again, you should now see that you have a failing test.

Now you just need to implement the functionality to make this work.

Defining custom M types

The schema enforcement approach in the previous lesson used "schema tables" defined as Name/Type pairs. It works well when working with flattened/relational data, but didn't support setting types on nested records/tables/lists, or allow you to reuse type definitions across tables/entities.

In the TripPin case, the data in the People and Airports entities contain structured columns, and even share a type (Location) for representing address information. Rather than defining Name/Type pairs in a schema table, you'll define each of these entities using custom M type declarations.

Here is a quick refresher about types in the M language from the Language Specification:

A type value is a value that classifies other values. A value that is classified by a type is said to conform to that type. The M type system consists of the following kinds of types:

- Primitive types, which classify primitive values (

binary,date,datetime,datetimezone,duration,list,logical,null,number,record,text,time,type) and also include a number of abstract types (function,table,any, andnone)- Record types, which classify record values based on field names and value types

- List types, which classify lists using a single item base type

- Function types, which classify function values based on the types of their parameters and return values

- Table types, which classify table values based on column names, column types, and keys

- Nullable types, which classifies the value null in addition to all the values classified by a base type

- Type types, which classify values that are types

Using the raw JSON output you get (and/or looking up the definitions in the service's $metadata), you can define the following record types to represent OData complex types:

LocationType = type [

Address = text,

City = CityType,

Loc = LocType

];

CityType = type [

CountryRegion = text,

Name = text,

Region = text

];

LocType = type [

#"type" = text,

coordinates = {number},

crs = CrsType

];

CrsType = type [

#"type" = text,

properties = record

];

Note how the LocationType references the CityType and LocType to represent its structured columns.

For the top level entities (that you want represented as Tables), you define table types:

AirlinesType = type table [

AirlineCode = text,

Name = text

];

AirportsType = type table [

Name = text,

IataCode = text,

Location = LocationType

];

PeopleType = type table [

UserName = text,

FirstName = text,

LastName = text,

Emails = {text},

AddressInfo = {nullable LocationType},

Gender = nullable text,

Concurrency = Int64.Type

];

You then update your SchemaTable variable (which you use as a "lookup table" for entity to type mappings) to use these new type definitions:

SchemaTable = #table({"Entity", "Type"}, {

{"Airlines", AirlinesType },

{"Airports", AirportsType },

{"People", PeopleType}

});

Enforcing a schema using types

You'll rely on a common function (Table.ChangeType) to enforce a schema on your data, much like you used SchemaTransformTable in the previous lesson.

Unlike SchemaTransformTable, Table.ChangeType takes in an actual M table type as an argument, and will apply your schema recursively for all nested types. Its signature looks like this:

Table.ChangeType = (table, tableType as type) as nullable table => ...

The full code listing for the Table.ChangeType function can be found in the Table.ChangeType.pqm file.

Note

For flexibility, the function can be used on tables, as well as lists of records (which is how tables would be represented in a JSON document).

You then need to update the connector code to change the schema parameter from a table to a type, and add a call to Table.ChangeType in GetEntity.

GetEntity = (url as text, entity as text) as table =>

let

fullUrl = Uri.Combine(url, entity),

schema = GetSchemaForEntity(entity),

result = TripPin.Feed(fullUrl, schema),

appliedSchema = Table.ChangeType(result, schema)

in

appliedSchema;

GetPage is updated to use the list of fields from the schema (to know the names of what to expand when you get the results), but leaves the actual schema enforcement to GetEntity.

GetPage = (url as text, optional schema as type) as table =>

let

response = Web.Contents(url, [ Headers = DefaultRequestHeaders ]),

body = Json.Document(response),

nextLink = GetNextLink(body),

// If we have no schema, use Table.FromRecords() instead

// (and hope that our results all have the same fields).

// If we have a schema, expand the record using its field names

data =

if (schema <> null) then

Table.FromRecords(body[value])

else

let

// convert the list of records into a table (single column of records)

asTable = Table.FromList(body[value], Splitter.SplitByNothing(), {"Column1"}),

fields = Record.FieldNames(Type.RecordFields(Type.TableRow(schema))),

expanded = Table.ExpandRecordColumn(asTable, fields)

in

expanded

in

data meta [NextLink = nextLink];

Confirming that nested types are being set

The definition for your PeopleType now sets the Emails field to a list of text ({text}).

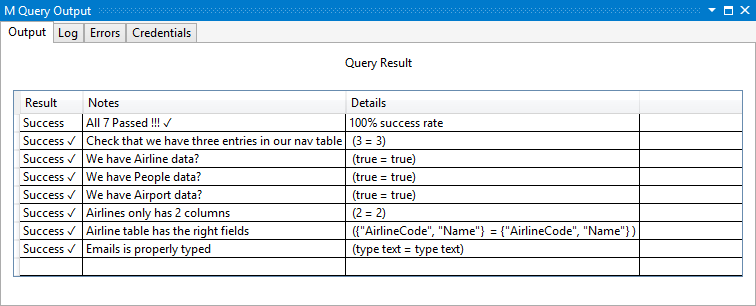

If you're applying the types correctly, the call to Type.ListItem in your unit test should now be returning type text rather than type any.

Running your unit tests again show that they are now all passing.

Refactoring common code into separate files

Note

The M engine will have improved support for referencing external modules/common code in the future, but this approach should carry you through until then.

At this point, your extension almost has as much "common" code as TripPin connector code. In the future these common functions will either be part of the built-in standard function library, or you'll be able to reference them from another extension. For now, you refactor your code in the following way:

- Move the reusable functions to separate files (.pqm).

- Set the Build Action property on the file to Compile to make sure it gets included in your extension file during the build.

- Define a function to load the code using Expression.Evaluate.

- Load each of the common functions you want to use.

The code to do this is included in the snippet below:

Extension.LoadFunction = (fileName as text) =>

let

binary = Extension.Contents(fileName),

asText = Text.FromBinary(binary)

in

try

Expression.Evaluate(asText, #shared)

catch (e) =>

error [

Reason = "Extension.LoadFunction Failure",

Message.Format = "Loading '#{0}' failed - '#{1}': '#{2}'",

Message.Parameters = {fileName, e[Reason], e[Message]},

Detail = [File = fileName, Error = e]

];

Table.ChangeType = Extension.LoadFunction("Table.ChangeType.pqm");

Table.GenerateByPage = Extension.LoadFunction("Table.GenerateByPage.pqm");

Table.ToNavigationTable = Extension.LoadFunction("Table.ToNavigationTable.pqm");

Conclusion

This tutorial made a number of improvements to the way you enforce a schema on the data you get from a REST API. The connector is currently hard coding its schema information, which has a performance benefit at runtime, but is unable to adapt to changes in the service's metadata overtime. Future tutorials will move to a purely dynamic approach that will infer the schema from the service's $metadata document.

In addition to the schema changes, this tutorial added Unit Tests for your code, and refactored the common helper functions into separate files to improve overall readability.