Infrastructure as code

Before the cloud, when an organization needed to build out its computing infrastructure, it deployed new physical servers and added them to the network behind a load balancer and firewall. When an Operations Manager had to estimate the capital expenditures required to support added capacity, those estimates were rendered in terms of whole servers. "Architecture" was conducted by calculator. One of the tips of capacity planning at the time was to add a "cushion", or overestimate, of 20 percent in case the initial estimates were too low.

The cloud changed that by offering computing infrastructure as a service. Suddenly adding capacity became a matter of clicking buttons in a portal, typing commands into a console, or running scripts. This ease created a new set of challenges. Given an entire solution made up of dozens or even hundreds of cloud services can be deployed in minutes by a single person, how can you make sure solutions are properly deployed, individual resources are properly configured, and the operator didn't make a mistake? How do you reliably modify a solution after it's deployed while minimizing the potential for human error? Scripting is one solution, but as we learned in the previous lesson, it solves certain problems while introducing others.

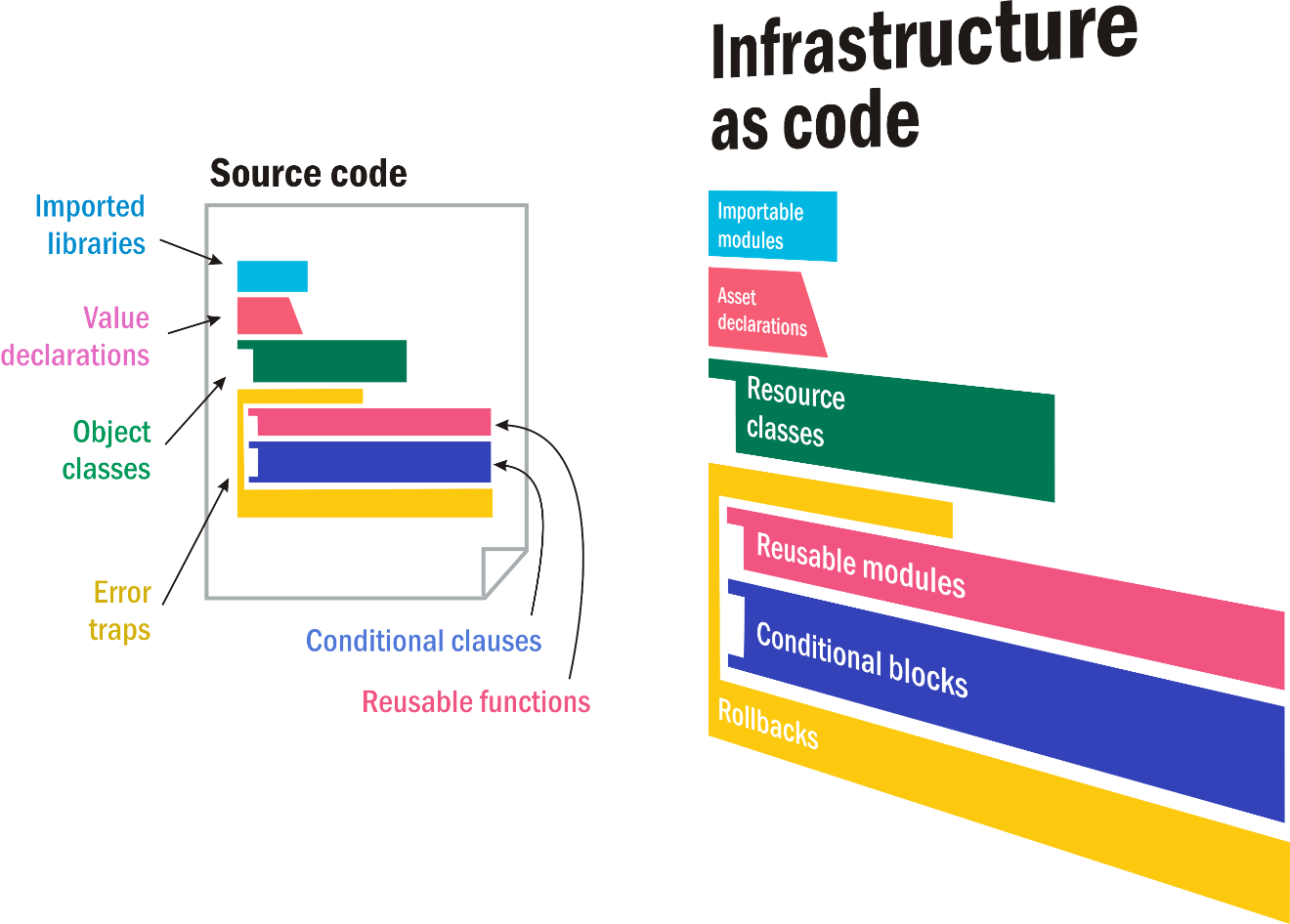

The next step on the journey to automating the processes used for to manage cloud infrastructure is Infrastructure-as-Code, or IaC. The idea of IaC is to explicitly define a solution deployed to the cloud in a dynamic way, like a program. Run the program and you create a solution; change the program, and you change the solution. IaC provides a mechanism for defining what a solution looks like. It contains many of the elements of a program without necessarily relying on a programming language: declaration of assets (variables), reusable functions and procedures, error trapping and recovery, and most importantly of all, formal support for testing and debugging (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Parallels between Infrastructure-as-Code and software programs.

IaC relies on configuration files that are similar to source code for application programs. An IaC configuration file might not look like source code, and it probably isn't written in Python or another traditional programming language. Yet all the major components a software developer would look for are there, just with a different syntax. A configuration file may lack commands or step-by-step procedures a Python program or a PowerShell script has, but it defines both an outcome and a process for achieving that outcome just the same.

This strategy is the concept of Infrastructure-as-Code. Cloud dynamics makes solution resources fluid and not constrained by the boundaries of the machines that support them. A system that oversees their management shouldn't be constrained by those boundaries either, treating the entire data center, on-premises and off-, as if it were one programmable, composable machine.

The introduction of configuration management

Many industries besides IT benefit from configuration management (CM), particularly in manufacturing and production. In automotive production, CM refers to the methods and processes used to manufacture a product that meets specific standards or customer requirements. In industrial equipment manufacturing, which produces parts used to build machines, there are parts-numbering systems, release-management systems, change-management systems, and status-accounting systems, which all must be coordinated to produce a repeatable outcome.

Automating configuration management in IT isn't that different. It involves managing systems in transitioning states. And it involves coordinating various subsystems so they work together. Philosophical questions are a current issue for IT administrators: Should the system maintain and preserve the processes by which cloud-based infrastructure is provisioned and assembled? Or should it instead define the infrastructural components necessary for meeting customer or user requirements, and figure out how to meet those requirements based on the infrastructure's current status? There are CM systems in use today that take one approach or the other.

In 1993, while the notion of virtualization in the data center was still in its infancy, an Oslo University quantum-field-theory researcher named Mark Burgess produced in his spare time, and in-between government-funded projects into thermal field theory1, what's believed to be the first modern configuration-management tool. Called CFEngine, it began as a domain-specific language that implemented conditional tests based on criteria from a computer's configuration. These tests were used to determine which instructions to execute to get the system to a desired configuration state.

As they evolved, the criteria for these conditional tests became phrased like declarations --- statements describing what the desired state of the system should be. Until then, a system configuration was described as an initial state of a system that undergoes a sequence of transformations. The same can be used to characterize a typical administrative script: a list of everything a CLI interpreter needs to do to amend the state of an existing system, or to build something into a state beginning with nothing.

Seven years later, for his important textbook on network and system administration2, Burgess effectively defined the use of the term "infrastructure" to refer to the resources that collectively make up and support the data center. There, he also put forth his five requirements for any data center's infrastructure to be considered stable: scalability, reliability, redundancy, homogeneity, and reproducibility.

Burgess believed it was possible to meet those requirements through a configuration-management system whose language has its developer start with the desired end state, and let the system guide development backwards towards the present state. In an essay published on his personal Web site3, Burgess describes the direction that conventional scripting tends to go as congruence, which he likened to a recipe leading someone through the steps of how to build something without describing what that something is. The direction he prefers is convergence, which he compares to using a map showing the destination and planning a route that leads back to where you are now.

Next generation configuration management

In 2006, open-source software developer Luke Kanies released under the General Public License (GPL) a tool he called Puppet. Describing it as "Next Generation Configuration Management4," he introduced it to his fellow IT professionals as an "operating system abstraction layer." That phrase didn't catch on, but the idea did. His premise was that the language of a configuration-management system should declare the required components of a type of resources such as virtual machines. The system could then be in charge of taking whatever steps necessary to meet those requirements, or something close to them, even when the sequence of those steps was likely to change. Further details about the Puppet language and how the system works are presented in the next lesson.

With Puppet, an operator can specify a class of service, which is made up of application packages and the other resources required to deliver something to users. The job of the configuration-management system becomes to provision the proper resources needed to deliver that service, as it has been classified within Puppet. This may involve provisioning virtual machines or, with more recent containerized systems, instantiating containers and the resources that support them.

DevOps - developers and operators

Almost the very moment an enterprise begins thinking about using Infrastructure as Code, it begins discussing whether two historically separate departments --- IT administration and software development --- should coalesce. The DevOps movement came from the idea that any plan at this level of the business can't be undertaken by two organizationally separate teams.

The "DevOps" term is attributed to inspiration from a 2009 computer-industry conference, during which two of the speakers were John Allspaw, at the time head of technical operations, and Paul Hammond, head of the engineering team, at photo-sharing service Flickr. Their joint session introduced this notion, which at the time was radical: If data-center infrastructure could be made adaptable and responsive to the changing needs of workloads, then it could support applications and services with much shorter release cycles, and much faster rates of deployment and continuous improvement.

IaC, continuous integration and continuous deployment (CI/CD), and the realignment of teams around projects and goals rather than managers and org charts, have been joined together as part of the same evolutionary trend. This trend is leading to organizational changes in the business that people outside of the IT department can recognize and appreciate:

The impact of DevOps

- Software is being developed faster

- Testing is being treated more seriously and rigorously.

- Infrastructure management tools are being integrated with automation servers

- Management methods for software teams are being used for IT teams

Software is being developed faster

Or for those organizations that have never developed their own applications or services, software is being developed where it wasn't being developed before. Release cycles for software used to be extended for months, even years, until a set delivery time on the itinerary that was convenient for the entire organization. One reason for such extensions was to allow windows of opportunity for hardware to be upgraded or replaced, or entirely new data centers to be established, just before a software release that would otherwise be impacted by an infrastructure shift mid-cycle. With cloud platforms now enabling operators to make more incremental changes to their infrastructure more frequently, there's no longer reason to delay software-release cycles.

Testing is being treated more seriously and rigorously

In a data-center environment that has adopted CI/CD, software is tested in at least one separate phase, perhaps two, before it's released into production. It may not be practical to construct similar development and staging phases for cloud infrastructure, but IaC tools do allow for "dry run" planning, where administrators can observe and predict the effects of changes applied to cloud solutions before they're committed.

Infrastructure management tools are being integrated with automation servers

Automation servers such as Jenkins are being used to to deliver infrastructure changes. As a result, the same "pipelined" itinerary used to plan the release cycles for applications and services are synchronized with infrastructure plans, recipes (Chef), or playbooks (Ansible), so the state of the infrastructure is always aligned with the workloads it supports.

Management methods for software teams are being used for IT teams

Agile methodologies are extending to operations teams. In an Agile framework, a smaller team with a project leader defines simpler goals that can be achieved in shorter intervals, driving towards those goals more methodically. Multiple teams may coordinate with one another, and consequently may more accurately gauge their progress. An Agile, or Agile-like, operations team may be more closely aligned with a software team in ensuring that infrastructure resources are available and can be relied upon.

IaC is merely an abstract concept without tools to implement it. The next lesson introduces some of the more widely adopted configuration-management tools, all of which embrace the notion of Infrastructure-as-Code to varying degrees.

References

Mark Burgess's personal webpage. http://markburgess.org/bio.html.

Wiley Publishing. Principles of Network and System Administration. https://www.wiley.com/Principles+of+Network+and+System+Administration%2C+2nd+Edition-p-9780470868072.

Mark Burgess's blog. http://markburgess.org/blog_cd.html.

usenix. Puppet: Next-Generation Configuration Management. https://www.usenix.org/publications/login/february-2006-volume-31-number-1/puppet-next-generation-configuration-management.