Understanding nullability

If you're a .NET developer, chances are you've encountered the System.NullReferenceException. This occurs at run time when a null is dereferenced; that is, when a variable is evaluated at runtime, but the variable refers to null. This exception is by far the most commonly occurring exception within the .NET ecosystem. The creator of null, Sir Tony Hoare, refers to null as the "billion-dollar mistake."

In the following example, the FooBar variable is assigned to null and immediately dereferenced, thus exhibiting the problem:

// Declare variable and assign it as null.

FooBar fooBar = null;

// Dereference variable by calling ToString.

// This will throw a NullReferenceException.

_ = fooBar.ToString();

// The FooBar type definition.

record FooBar(int Id, string Name);

The problem becomes much more difficult to spot as a developer when your apps grow in size and complexity. Spotting potential errors like this is a job for tooling, and the C# compiler is here to help.

Defining null safety

The term null safety defines a set of features specific to nullable types that help reduce the number of possible NullReferenceException occurrences.

Considering the previous FooBar example, you could avoid the NullReferenceException by checking if the fooBar variable was null before dereferencing it:

// Declare variable and assign it as null.

FooBar fooBar = null;

// Check for null

if (fooBar is not null)

{

_ = fooBar.ToString();

}

// The FooBar type definition for example.

record FooBar(int Id, string Name);

To aid in identifying scenarios like this, the compiler can infer the intent of your code and enforce the behavior desired. However, this is only when a nullable context is enabled. Before discussing nullable context, let's describe the possible nullable types.

Nullable types

Before C# 2.0, only reference types were nullable. Value-types such as int or DateTime couldn't be null. If these types are initialized without a value, they fall back to their default value. In the case of an int, this is 0. For a DateTime, it's DateTime.MinValue.

Reference types instantiated without initial values work differently. The default value for all reference types is null.

Consider the following C# snippet:

string first; // first is null

string second = string.Empty // second is not null, instead it's an empty string ""

int third; // third is 0 because int is a value type

DateTime date; // date is DateTime.MinValue

In the preceding example:

firstisnullbecause the reference typestringwas declared but no assignment was made.secondis assignedstring.Emptywhen it's declared. The object never had anullassignment.thirdis0despite not being assigned. It's astruct(value-type) and has adefaultvalue of0.dateis uninitialized, but itsdefaultvalue is System.DateTime.MinValue.

Starting with C# 2.0, you could define nullable value types using Nullable<T> (or T? for shorthand). This allows value-types to be nullable. Consider the following C# snippet:

int? first; // first is implicitly null (uninitialized)

int? second = null; // second is explicitly null

int? third = default; // third is null as the default value for Nullable<Int32> is null

int? fourth = new(); // fourth is 0, since new calls the nullable constructor

In the preceding example:

firstisnullbecause the nullable value type is uninitialized.secondis assignednullwhen it's declared.thirdisnullas thedefaultvalue forNullable<int>isnull.fourthis0as thenew()expression calls theNullable<int>constructor, andintis0by default.

C# 8.0 introduced nullable reference types, where you can express your intent that a reference type might be null or is always non-null. You may be thinking, "I thought all reference types are nullable!" You're not wrong, and they are. This feature allows you to express your intent, which the compiler then tries to enforce. The same T? syntax expresses that a reference type is intended to be nullable.

Consider the following C# snippet:

#nullable enable

string first = string.Empty;

string second;

string? third;

Given the preceding example, the compiler infers your intent as follows:

firstis nevernullas it is definitely assigned.secondshould never benull, even though it's initiallynull. Evaluatingsecondbefore assigning a value results in a compiler warning as it is uninitialized.thirdmight benull. For example, it might point to aSystem.String, but it might point tonull. Either of these variations are acceptable. The compiler helps you by warning you if you dereferencethirdwithout first checking that it isn't null.

Important

In order to use the nullable reference types feature as shown above, it must be within a nullable context. This is detailed in the next section.

Nullable context

Nullable contexts enable fine-grained control for how the compiler interprets reference type variables. There are four possible nullable contexts:

disable: The compiler behaves similarly to C# 7.3 and earlier.enable: The compiler enables all null reference analysis and all language features.warnings: The compiler performs all null analysis and emits warnings when code might dereferencenull.annotations: The compiler doesn't perform null analysis or emit warnings when code might dereferencenull, but you can still annotate your code using nullable reference types?and null-forgiving operators (!).

This module is scoped to either disable or enable nullable contexts. For more information, reference Nullable reference types: Nullable contexts.

Enable nullable reference types

In the C# project file (.csproj), add a child <Nullable> node to the <Project> element (or append to an existing <PropertyGroup>). This will apply the enable nullable context to the entire project.

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<OutputType>Exe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>net6.0</TargetFramework>

<Nullable>enable</Nullable>

</PropertyGroup>

<!-- Omitted for brevity -->

</Project>

Alternatively, you can scope nullable context to a C# file using a compiler directive.

#nullable enable

The preceding C# compiler directive is functionally equivalent to the project configuration, but it's scoped to the file in which it resides. For more information, see Nullable reference types: Nullable contexts (docs)

Important

The nullable context is enabled in the .csproj file by default in all C# project templates starting with .NET 6.0 and greater.

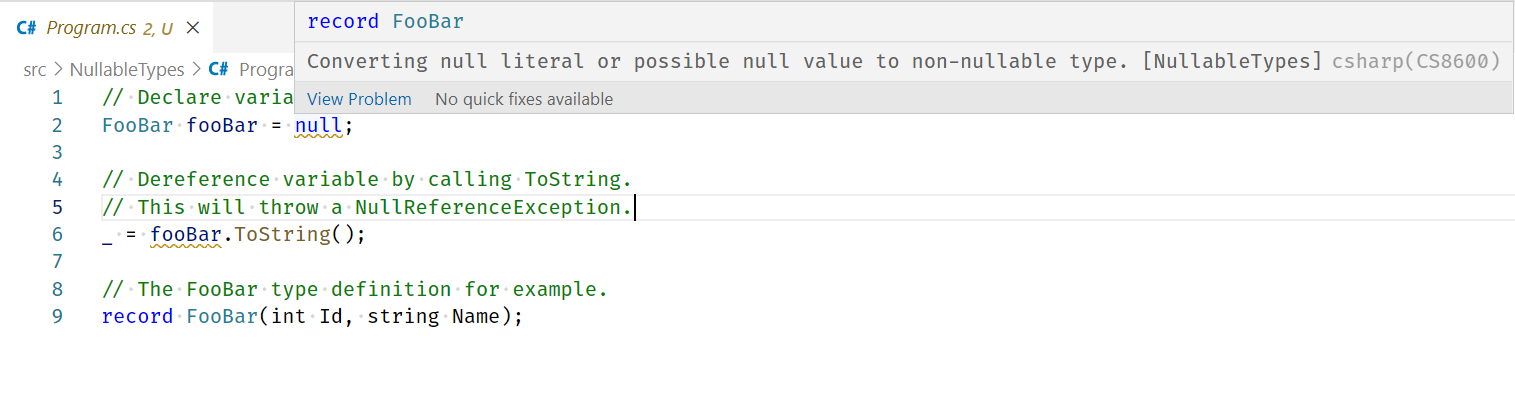

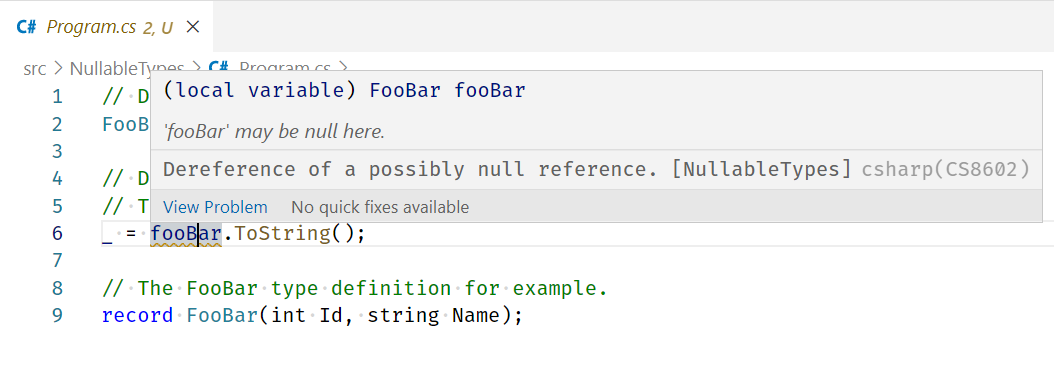

When the nullable context is enabled, you'll get new warnings. Consider the previous FooBar example, which has two warnings when analyzed in a nullable context:

The

FooBar fooBar = null;line has a warning on thenullassignment: C# Warning CS8600: Converting null literal or possible null value to non-nullable type.The

_ = fooBar.ToString();line also has a warning. This time the compiler is concerned thatfooBarmay be null: C# Warning CS8602: Dereference of a possibly null reference.

Important

There is no guaranteed null safety, even if you react to and eliminate all the warnings. There are some limited scenarios that will pass the compiler's analysis, yet result in a runtime NullReferenceException.

Summary

In this unit, you learned to enable a nullable context in C# to help guard against NullReferenceException. In the next unit, you'll learn more about explicitly expressing your intent in a nullable context.