Manage dependency updates in your .NET project

Sooner or later, you want to update to a new version of a library. Maybe a function is marked as deprecated, or maybe there's a new feature in a later version of a package you're using.

Take these considerations into account before you try to update a library:

- The type of update: What type of update is available? Is it a small bug fix? Is it adding a new feature that you need? Does it break your code? You can communicate the type of update by using a system called semantic versioning. The way the library's version number is expressed communicates to developers the type of update with which they're dealing.

- Whether the project is configured correctly: You can configure your .NET project so that you get only the types of updates you want. You perform an update only if a specific type of update is available. We recommend this approach, because you don't risk running into surprises.

- Security problems: Managing your project dependencies over time involves being aware of problems that might happen. Problems arise as vulnerabilities are detected, for example. Ideally, patches are released that you can download. The .NET Core tool helps you run an audit on your libraries to find out if you have packages that should be updated. It also helps you take the appropriate action to fix a problem.

Use semantic versioning

There's an industry standard called semantic versioning, which is how you express the type of change that you or some other developer is introducing to a library. Semantic versioning works by ensuring that a package has a version number, and that the version number is divided into these sections:

- Major version: The leftmost number. For example, it's the

1in1.0.0. A change to this number means that you can expect "breaking changes" in your code. You might need to rewrite part of your code. - Minor version: The middle number. For example, it's the

2in1.2.0. A change to this number means that features were added. Your code should still work. It's typically safe to accept the update. - Patch version: The rightmost number. For example, it's the

3in1.2.3. A change to this number means that a change was applied that fixes something in the code that should be working. It should be safe to accept the update.

This table illustrates how the version number changes for each version type:

| Type | What happens |

|---|---|

| Major version | 1.0.0 changes to 2.0.0 |

| Minor version | 1.1.1 changes to 1.2.0 |

| Patch version | 1.0.1 changes to 1.0.2 |

Many companies and developers use this system. If you intend to publish packages and push them to the NuGet registry, you're expected to follow semantic versioning. Even if you only download packages from the NuGet registry, you can expect these packages to follow semantic versioning.

Changes to a package can introduce risk, including the risk that a bug might harm your business. Some risks might require you to rewrite part of your code. Rewriting code takes time and costs money.

Update approach

As a .NET developer, you can communicate the update behavior that you want to .NET. Think about updating in terms of risk. Here are some approaches:

- Major version: I'm OK with updating to the latest major version as soon as it's out. I accept the fact that I might need to change code on my end.

- Minor version: I'm OK with a new feature being added. I'm not OK with code that breaks.

- Patch version: The only updates I'm OK with are bug fixes.

If you're managing a new or smaller .NET project, you can afford to be loose with how you define the update strategy. For example, you can always update to the latest version. For more complex projects, there's more nuance, but we'll save that for a future module.

In general, the smaller the dependency you're updating, the fewer dependencies it has and the more likely that the update process is easy.

Configure the project file for update

When you're adding one or more dependencies, configure your project file so that you get predictable behavior when you restore, build, or run your project. You can communicate the approach that you want to take for a package. NuGet has the concepts of version ranges and floating versions.

Version ranges are a special notation that you can use to indicate a specific range of versions that you want to resolve.

| Notation | Applied rule | Description |

|---|---|---|

1.0 |

x >= 1.0 | Minimum version, inclusive |

(1.0,) |

x > 1.0 | Minimum version, exclusive |

[1.0] |

x == 1.0 | Exact version match |

(,1.0] |

x ≤ 1.0 | Maximum version, inclusive |

(,1.0) |

x < 1.0 | Maximum version, exclusive |

[1.0,2.0] |

1.0 ≤ x ≤ 2.0 | Exact range, inclusive |

(1.0,2.0) |

1.0 < x < 2.0 | Exact range, exclusive |

[1.0,2.0) |

1.0 ≤ x < 2.0 | Mixed inclusive minimum and exclusive maximum version |

(1.0) |

invalid | invalid |

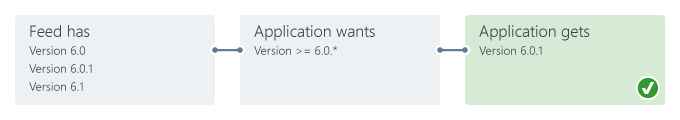

NuGet also supports using a floating version notation for major, minor, patch, and prerelease suffix parts of the number. This notation is an asterisk (*). For example, the version specification 6.0.* says "use the latest 6.0.x version." In another example, 4.* means "use the latest 4.x version." Using a floating version reduces changes to the project file while keeping up to date with the latest version of a dependency.

Note

We recommend installing a specific version instead of using any of the floating notations. Installing a specific version ensures that your builds are repeatable unless you explicitly request an update to a dependency.

When you're using a floating version, NuGet resolves the latest version of a package that matches the version pattern. In the following example, 6.0.* gets the latest version of a package that starts with 6.0. That version is 6.0.1.

Here are some examples that can configure for major, minor, or patch version:

<!-- Accepts any version 6.1 and later. -->

<PackageReference Include="ExamplePackage" Version="6.1" />

<!-- Accepts any 6.x.y version. -->

<PackageReference Include="ExamplePackage" Version="6.*" />

<PackageReference Include="ExamplePackage" Version="[6,7)" />

<!-- Accepts any later version, but not including 4.1.3. Could be

used to guarantee a dependency with a specific bug fix. -->

<PackageReference Include="ExamplePackage" Version="(4.1.3,)" />

<!-- Accepts any version earlier than 5.x, which might be used to prevent pulling in a later

version of a dependency that changed its interface. However, we don't recommend this form because determining the earliest version can be difficult. -->

<PackageReference Include="ExamplePackage" Version="(,5.0)" />

<!-- Accepts any 1.x or 2.x version, but not 0.x or 3.x and later. -->

<PackageReference Include="ExamplePackage" Version="[1,3)" />

<!-- Accepts 1.3.2 up to 1.4.x, but not 1.5 and later. -->

<PackageReference Include="ExamplePackage" Version="[1.3.2,1.5)" />

Find and update outdated packages

The dotnet list package --outdated command lists outdated packages. This command can help you learn when newer versions of packages are available. Here's a typical output from the command:

Top-level Package Requested Resolved Latest

> Humanizer 2.7.* 2.7.9 2.8.26

Here are the meanings of the names of the columns in the output:

Requested: The version or version range that you specified.Resolved: The actual version downloaded for the project that matches the specified version.Latest: The latest version available for update from NuGet.

The recommended workflow is to run the following commands, in this order:

- Run

dotnet list package --outdated. This command lists all the outdated packages. It provides information in theRequested,Resolved, andLatestcolumns. - Run

dotnet add package <package name>. If you run this command, it tries to update to the latest version. Optionally, you can pass in--version=<version number/range>.