Explore the domain name system

DNS is a service that manages the resolution of host names to IP addresses. Microsoft provides a DNS Server role on Windows Server that you can use to resolve host names in your organization. Typically, you will deploy multiple DNS servers in your organization to help improve both the performance and the reliability of name resolution.

Note

The Internet uses a single DNS namespace with multiple root servers. To participate in the Internet DNS namespace, you must register a domain name with a DNS registrar. This ensures that no two organizations attempt to use the same domain name.

Structure of DNS

The DNS namespace consists of a hierarchy of domains and subdomains. A DNS zone is a specific portion of that namespace that resides on a DNS server in a zone file. DNS uses both forward and reverse lookup zones to satisfy name resolution requests.

Forward lookup zones

Forward lookup zones are capable of hosting a number of different record types. The most common record type in forward lookup zones is an A record, also known as a host record. This record is used when resolving a host name to an IP address. Record types in forward lookup zones include:

- A. A host record, the most common type of DNS record.

- SRV. Service records are used to locate domain controllers and global catalog servers.

- MX. Mail exchange records are used to locate the mail servers responsible for a domain.

- CNAME. Canonical name records (CNAME records) resolve to another host name, also referred to as an alias.

Reverse lookup zones

Reverse lookup zones contain PTR records. PTR records are used to resolve IP addresses to host names. An organization typically has control over the reverse lookup zones for its internal network. However, some PTR records for external IP addresses obtained from an ISP could be managed by the ISP.

How names are resolved with DNS

Resolving DNS names on the Internet involves an entire system of computers, not just a single server. There are hundreds of servers on the Internet, called root servers, which manage the overall process of DNS resolution. 13 FQDNs represent these servers. A list of these 13 FQDNs is preloaded on each DNS server. When you register a domain name on the Internet, you are paying to become part of this system.

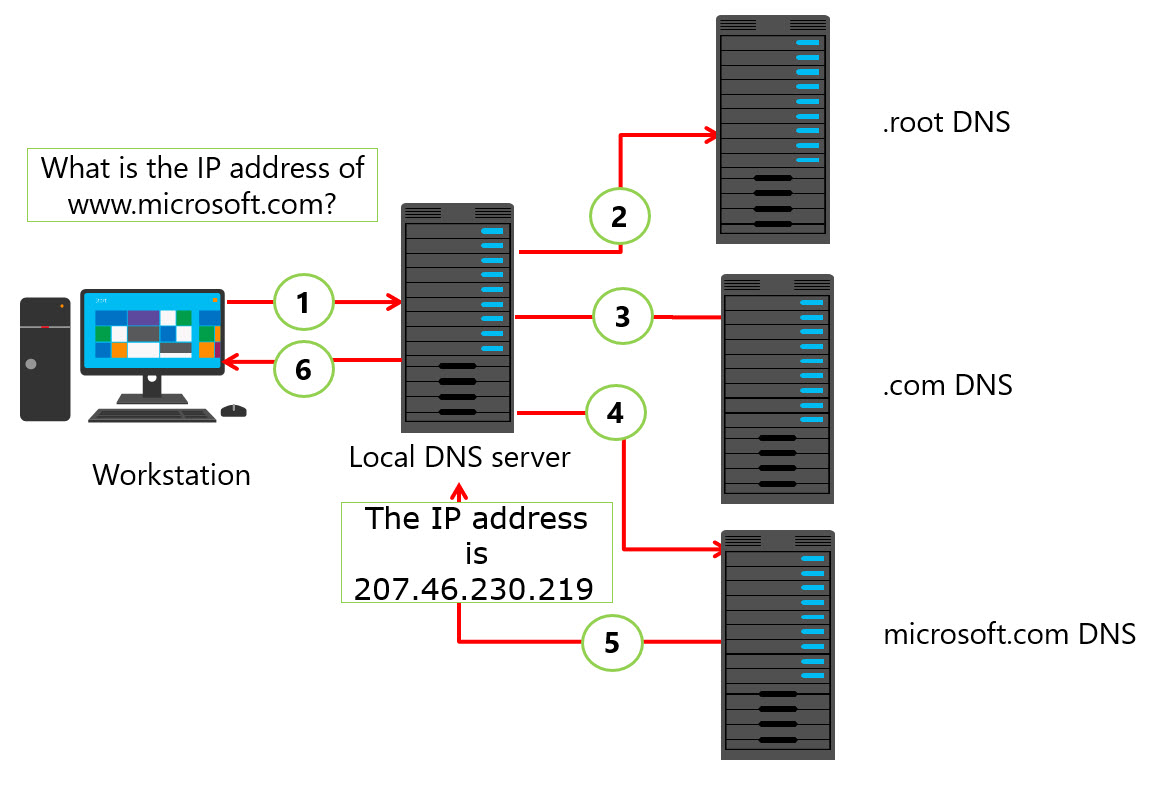

To understand how these servers work together to resolve a DNS name, see the following name resolution process for the name www.microsoft.com:

- A workstation queries the local DNS server for the IP address www.microsoft.com.

- If the local DNS server does not have the information, it queries a root DNS server for the location of the .com DNS servers.

- The local DNS server queries a .com DNS server for the location of the microsoft.com DNS servers.

- The local DNS server queries the microsoft.com DNS server for the IP address of www.microsoft.com.

- The microsoft.com DNS server returns the IP address of www.microsoft.com to the local DNS server.

- The local DNS server returns the result to the workstation.

Caching and forwarding can modify the name resolution process:

- Caching. After a local DNS server resolves a DNS name, it caches the results for the period that the Time to Live (TTL) value defines in the Start of Authority (SOA) record for the DNS zone. The default TTL is one hour. Subsequent resolution requests for the DNS name receive the cached information. Note that it is not the caching server that sets the TTL, but the authoritative DNS server that resolved the name from its zone. When the TTL expires, the caching server must delete it. Subsequent requests for the same name would require a new name resolution request to the authoritative server.

- Forwarding. Instead of querying root servers, you can configure a DNS server to forward DNS requests to another DNS server. For example, requests for all Internet names can be forwarded to a DNS server at an ISP.