How investment works

At its most basic, raising money from investors means to sell a stake in your company in return for cash. The investor obtains an economic interest in your company. They also gain some degree of control by virtue of the rights attached to their stake.

Bootstrapping vs. funding externally

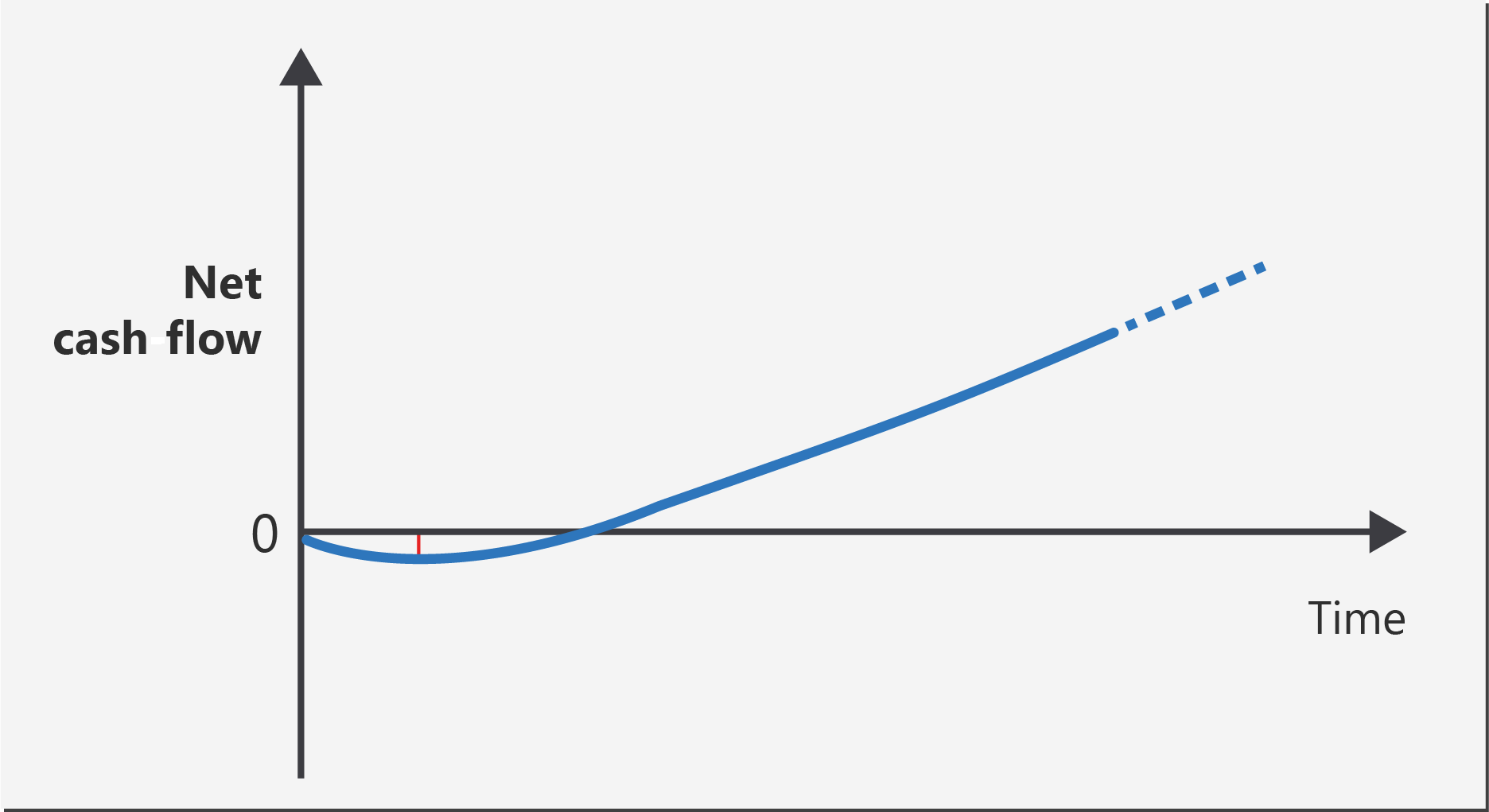

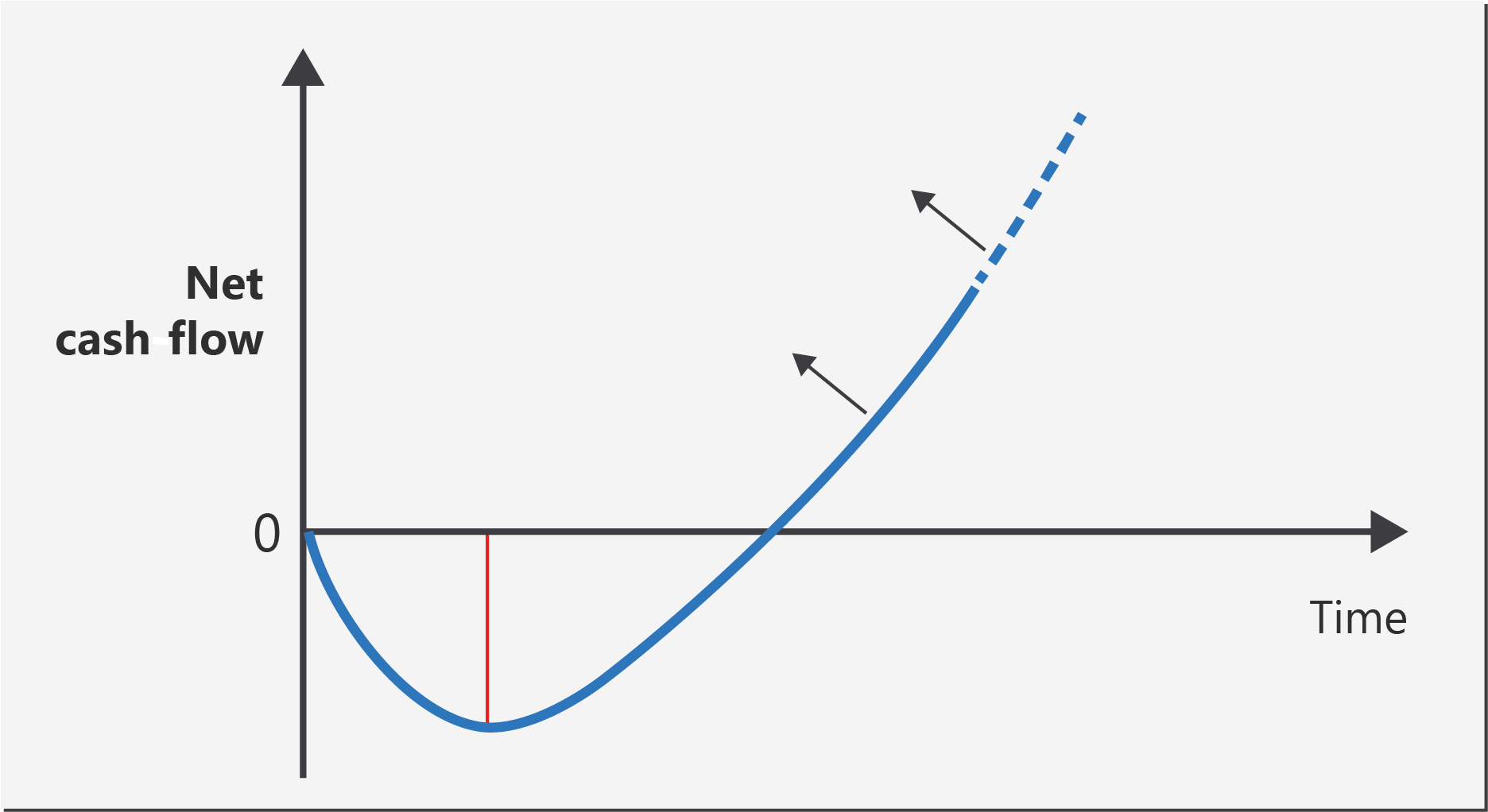

The difference between a bootstrapped company and an externally funded one can be seen in the following two charts, which show net cash flow over time.

In the first chart, the company is growing organically. The founders self-fund it until it can generate customer revenue. At that point, revenue is the main source of funding for continued growth. This type of funding is commonly referred to as bootstrapping.

A self-funded, or bootstrapped, company can tolerate negative cash flow only to the extent that the founders can fund the company personally. After the company begins to generate revenue and achieves positive cash flow, its rate of growth is limited by the rate at which revenue is generated.

The following chart shows cash flow in an externally funded startup. Such a company can tolerate a greater level of negative cash flow, which allows it to invest more in product development and customer acquisition. After the product is launched, it can achieve a steeper rate of growth.

Higher growth is one of the primary reasons that startup founders seek external capital to fund the growth of their companies.

Why raise money?

There are other reasons that startups raise money from investors beyond maximizing growth.

Having the backing of a good investor brings access to capital and expertise, both of which can greatly enhance your ability to grow your startup into a large and successful business.

In many cases, startups require a large up-front investment to build the product and get it in the hands of users before generating meaningful revenues. In these instances, it might not be feasible for the founders to self-fund the company, so raising external capital is the only option. This is especially true for deep-tech companies or those organizations that develop complex physical products.

If you're competing in a large and global market, you probably have competitors. If they have significant amounts of capital, you might not be able to compete meaningfully without access to similar amounts of capital. Bootstrapping your company with limited funding might make it impossible to compete in your market.

Why not raise money?

There are some good reasons why raising money from investors might not be a good fit for you.

First, you might not need external capital. If you can self-fund your company or generate customer revenue early enough, bootstrapping your startup can be the best path to take.

You also might not want to start a high-growth company and swing for the fences. Taking external capital from an investor brings with it a set of expectations. As we'll discuss later, most investors are interested only in backing companies that can experience massive growth and generate a large financial return. It makes sense to want to start a company that grows at a more modest pace. Such companies often provide founders with an ongoing source of income and allow them to be in control of their own work-life balance.

When you raise external capital, you're giving up some control over your company because you're no longer the sole owner. The company goes from being my company to our company.

One way to think through this decision is to weigh the advantages and disadvantages. On the downside, you have to give up some control. On the upside, you have the capital to increase the odds that the company grows and succeeds.

A worksheet like the Founder Alignment Exercise is a useful input to help you decide which kind of company you and your cofounders want to build.

Control and dilution

When you raise money from an investor, they'll want some input on how you run the company. They need this information to protect their investment and ensure that they're able to contribute positively to the company's growth.

Their input might take the form of a seat on your board of directors or a board observer position, or it might take place informally through regular meetings with the founders. It can also involve giving the investor voting and veto rights on key strategic decisions. Usually, a separate class of shares is issued to investors with these rights attached.

A good investor isn't interested in running your company, they just want to maximize its chance of success. Unless something goes terribly wrong, you and your cofounders will still be in charge of the company, making all the day-to-day decisions.

Nevertheless, many founders grapple with the question of giving up some control of their company.

It's important to separate the concepts of economic interest and control. As a startup raises more capital, the founders' shares are diluted by the incoming investors. When startups raise large amounts of money over multiple funding rounds, founders sometimes end up with a minority stake in the company they started.

This change doesn't necessarily mean they lose control over the company. An investor can have a significant economic interest in the company while having only a modest degree of control over it, but they still benefit financially when the company is successful.

By way of example, Mark Zuckerberg retains significant control over Meta (previously Facebook). He holds around 58 percent of voting stock, despite having raised billions of dollars from investors and being diluted to a minority shareholding with less than 20 percent of the company's total stock.

Funding rounds

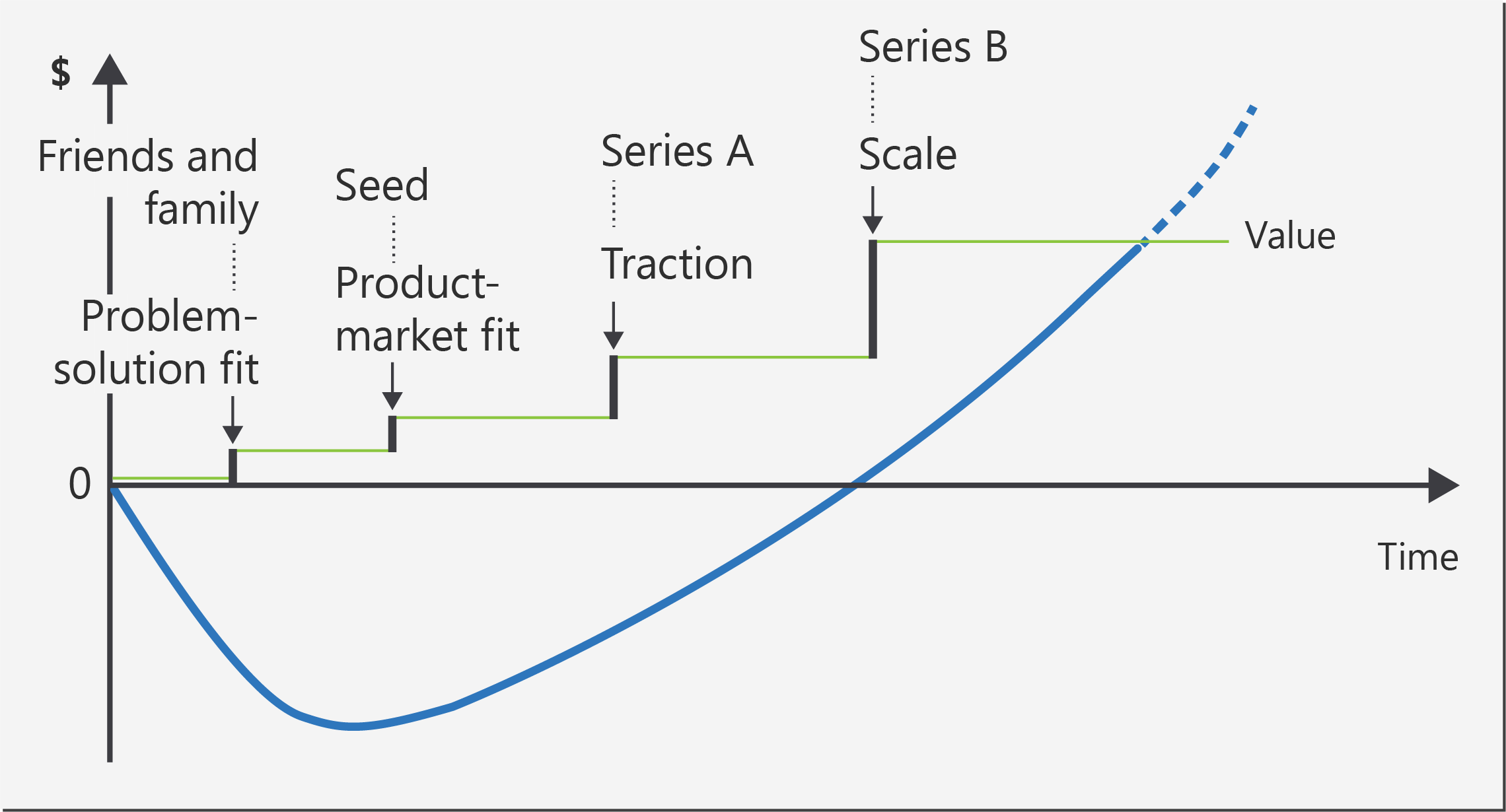

When startups raise money from investors, they typically do so in discrete stages, or funding rounds, that align with milestones in the company's development.

Each funding round is linked to achieving a certain level of de-risking of the opportunity. As the company goes from one funding round to the next, the amount invested generally increases, as does the valuation of the company.

The terminology used to describe each of these funding rounds varies considerably by geography and by industry. The most common terms and their meaning are summarized in the following sections. Each section describes a different funding round.

| Funding round | Typical company stage | Typical source of capital |

|---|---|---|

| Friends and family | Idea, concept design, prototype or minimal viable product (MVP) | People you know who want to support you as an entrepreneur and who might not want or expect a large financial return |

| Seed | MVP or product in market Evidence of problem-solution fit Early traction in the form of product usage and ideally some revenue |

Angel investors Seed-stage venture capital (VC) funds |

| Series A | Established market Evidence of product-market fit Growth in revenue limited by capital rather than by demand |

VC funds |

| Series B, C, D, E | Expansion to other products, markets, and geographies | VC funds, private equity firms |

You can plot these funding rounds on a time chart that shows the typical milestones against which each round is raised.

The investor perspective

Why do investors invest in startups? To answer this question, we first need to look at risk and return.

Investors typically have a portfolio of investments. Each investment can be characterized by two factors:

- Potential rate of return: How much money the investor could make for every dollar invested if the investment is successful.

- Level of risk: The level of uncertainty about whether it will generate that return.

The riskier an investment, the higher the rate of return an investor should expect in order to compensate them for taking the risk.

Generally speaking, at the low end of the risk-return spectrum are investments such as government bonds. Property and listed stocks are in the middle. Startups are at the top.

It's estimated that more than 90 percent of all startups fail and around 70 percent of seed-funded startups fail, so a seed-stage investor who invests in 10 startups can only expect three of those startups to succeed.

Experienced investors have no problem with accepting risk, but only if they can see the potential for a large return to compensate them for all the investments that didn't make it.

As a guide, early-stage investors look for at least a 30 percent annual rate of return across a portfolio of startup investments. For reference, the average annual return to investors in residential real estate is around 10.5 percent.

Investors need liquidity

Investors typically don't invest in your company for a dividend or a share of profits; instead, they want your company to achieve a liquidity event, which is also known as an exit.

An exit occurs when your company is either acquired by a larger company or listed on a stock exchange. Acquisitions are more common than listings. At this point, investors can sell their shares and receive a one-off sum. Founders, employees, and any other shareholders generally sell their shares too.

For founders, this means that if you intend to raise money from investors, you need to be clear from the outset that you're building an acquirable or publicly listable company.

For example, you might want to build a lifestyle business or a company that you hope will remain privately owned forever. You won't be able to raise money from most mainstream investors, such as angels and VC funds, because there might not be an opportunity for them to exit their investment.

Finally, it's important to recognize that investors are often themselves successful founders who exited one or more of their own companies. They might want to actively support other founders by reinvesting the wealth they generated. This is especially true in more mature startup ecosystems that have large numbers of successful serial entrepreneurs.

What investors look for

When an investor considers your company as an investment prospect, they're essentially assessing risk versus rate of return. The following indicators of failure are a good proxy for risk. The success indicators are a good proxy for rate of return. Investors score your company by considering each indicator in the following checklists.

| Success | Failure |

|---|---|

| ☐ Non-obvious idea | ☐ Building a product that nobody wants |

| ☐ The right team | ☐ A derivative idea |

| ☐ Intense customer pain | ☐ Competing with free |

| ☐ Scalable business model | ☐ Attempting to scale before achieving problem-solution fit |

| ☐ Large opportunity | ☐ Too concerned about secrecy |

| ☐ Timing | ☐ Not seeking out the right advice |

| ☐ Tailwinds | |

| ☐ Inherently shareable | |

| ☐ Recurring revenues |

Some other factors that investors consider when they make investment decisions include:

Growth levers: Actions that translate into growth in customers and revenue, such as paid acquisition, content marketing, or partnerships. Investors want to see that the founders have identified growth levers. When you apply capital to growth levers, you should generate more growth. Investors also want founders to prove that unit economics are positive. That means for every dollar you spend pulling a growth lever, you generate more than a dollar in revenue.

Validation: You've validated your riskiest assumptions. For instance, you've confirmed what product you should build and what customers you're building it for. You also have evidence that those customers see enough value to buy it.

Commitment: Founders need to be able to demonstrate to an investor that they're 100 percent committed to the company.

Many founders take a stepwise approach to committing time to their startup. This approach is reasonable. But when you're ready to raise funding, investors expect you to be working in your business full time and not as a side hustle.

Tip

Before you contact an investor, ensure your LinkedIn profile reflects your role as founder of your company.

Risk mitigation: Investors want to see that you've put in place some basic risk-mitigation measures, such as:

- Founder vesting to protect the company in case one of the founders leaves the company.

- Employment contracts with all founders and employees, including an intellectual property (IP) assignment to ensure the company has ownership of all relevant IP assets.

- Good governance practices, such as regular board meetings, even if prior to the investment the founders are the only directors.

- An employee stock-option program, if you have employees, to ensure maximum alignment of interests and retention of key personnel.

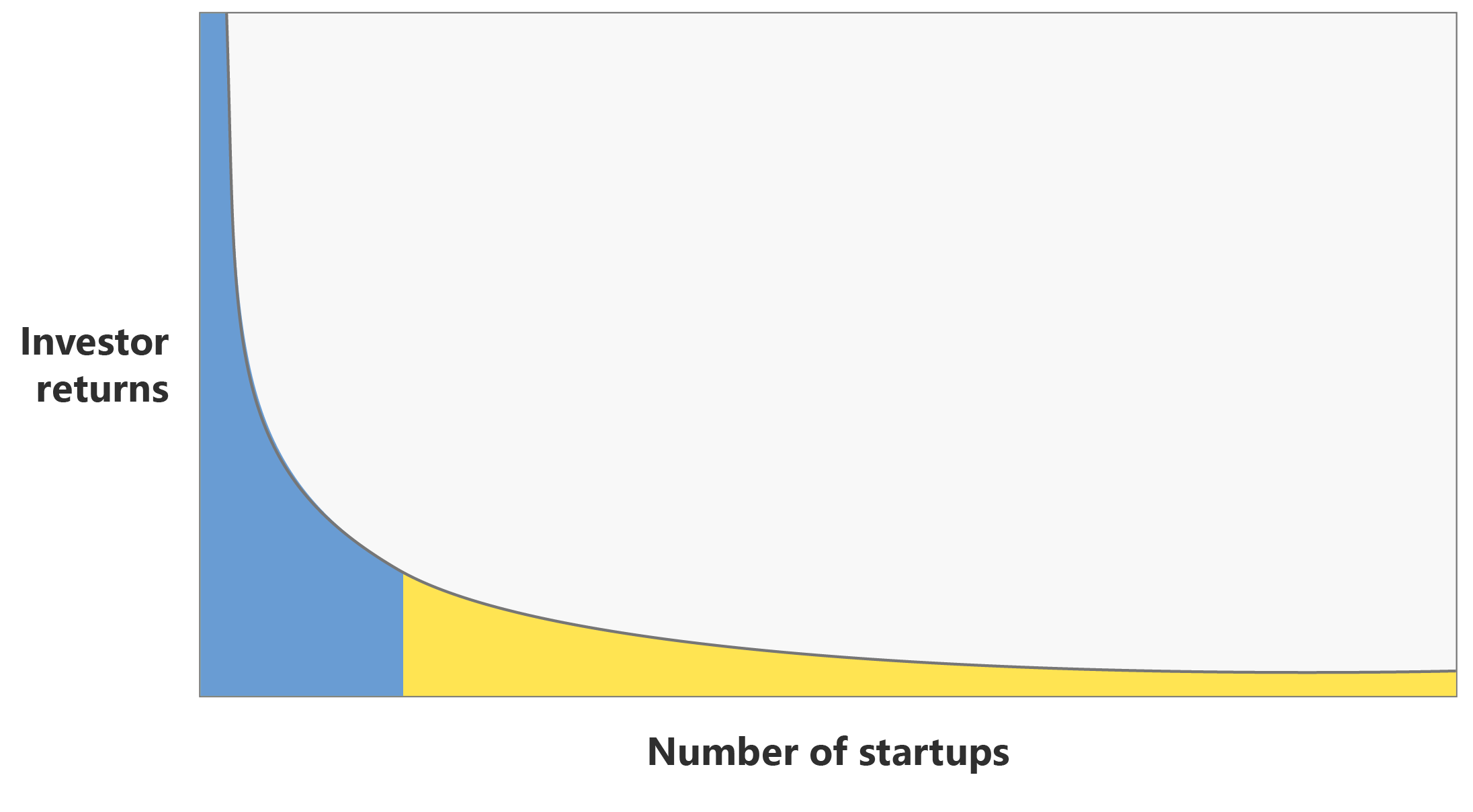

Investors look for outliers

Many early-stage investors see thousands of opportunities a year. They typically invest in only 1 to 2 percent of all the companies they see.

The reason for this low acceptance rate is that investor returns follow a power-law distribution. A few highly successful investments are worth many times more than all the other investments combined. Investors know that most startups in which they invest will fail. The small proportion of startups that succeed need to generate a large enough return to compensate for all the failed companies.

This concept is one of the most misunderstood ideas in startups. This misconception frequently leads founders to underestimate the scale of success their company needs to achieve for it to be considered investable.

Let's explore this concept further by working through a hypothetical angel investor's startup investment portfolio.

Scenario: An angel investor's perspective

Melanie is an angel investor. She decides to make seed-stage investments in 10 companies with an average investment of $100,000 in each company. These investments will take place over a period of a few years.

Melanie doesn't know which of the companies she backs will ultimately be successful, but realizes that each company she invests in must have a chance at being hugely successful. She makes her investments with this idea in mind.

Significant research has been done on angel investor portfolios. One of the consistent findings is that on average, at least half of all early-stage investments lead to no return. This result is typically either because the company fails completely, or it grows slowly and remains a privately owned company but never achieves a liquidity event. Investors sometimes refer to these investments as zombie companies.

As an experienced investor, Melanie knows this outcome is likely for a large proportion of the companies in which she invests. Like any sensible angel investor, she only invests money that she can afford to lose.

Let's look at Melanie's investment portfolio and assume from the outset that half of her investments generate zero return.

| Investee | Amount invested | Investor return on exit |

|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 2 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 3 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 4 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 5 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 6 | $100,000 | Unknown |

| Company 7 | $100,000 | Unknown |

| Company 8 | $100,000 | Unknown |

| Company 9 | $100,000 | Unknown |

| Company 10 | $100,000 | Unknown |

| Total | $1,000,000 | $0 |

Research also shows that out of every 10 angel investments, on average two make a one-time return, which is better than zero but not a successful outcome. This scenario sometimes occurs because the founders know the company isn't working out. They're able to do an orderly windup and return the investors' capital to them before the company completely fails.

Similarly, out of every 10 investments, on average two make a small positive return of two times to four times the amount invested. This scenario can occur when the company is acquired, meaning a small acquisition coupled with hiring the team that started the company. Again, this return is better than zero, but it's not the outcome that Melanie is seeking.

If we now look at Melanie's investment portfolio, we can populate nine of the 10 investment outcomes. Five failed, which generated zero return. Two generated a one-time return, and two more generated a two-time and a four-time return.

We can see that Melanie's portfolio return from these nine investments is $800,000.

| Investee | Amount invested | Investor return on exit |

|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 2 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 3 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 4 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 5 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 6 | $100,000 | $100,000 |

| Company 7 | $100,000 | $100,000 |

| Company 8 | $100,000 | $200,000 |

| Company 9 | $100,000 | $400,000 |

| Company 10 | $100,000 | Unknown |

| Total | $1,000,000 | $800,000 |

The table tells us that company number 10 must be the one that makes Melanie's investment portfolio a success overall. It needs to make up for the startups that failed and those companies that made a small return.

How well does company number 10 need to do? We can estimate this amount by working backwards from an expected portfolio rate of return. We noted earlier that seed-stage investors look for at least a 30 percent annual rate of return across their startup investment portfolio.

If Melanie invests $1 million and holds these investments for seven years, she needs to realize a $5 million return on her $1 million invested. A simple internal rate of return (IRR) calculation confirms this return.

A $5 million return might sound like a phenomenal outcome. That's $4 million more than Melanie invested. But remember that she's investing in risky startups and could've made a much safer return by investing in lower-risk assets.

If we know Melanie needs to make a $5 million portfolio return, and so far nine companies have returned only $800,000, we know that company 10 needs to generate a return of $4.2 million.

That's a return of $4.2 million on an investment of $100,000, or a 42-time return on Melanie's investment.

Melanie's portfolio would now look like the following table:

| Investee | Amount invested | Investor return on exit |

|---|---|---|

| Company 1 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 2 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 3 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 4 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 5 | $100,000 | $0 |

| Company 6 | $100,000 | $100,000 |

| Company 7 | $100,000 | $100,000 |

| Company 8 | $100,000 | $200,000 |

| Company 9 | $100,000 | $400,000 |

| Company 10 | $100,000 | $4,200,000 |

| Total | $1,000,000 | $5,000,000 |

Some startup founders might think that a 42-time return sounds egregious, but it's perfectly rational. If Melanie invests in 10 companies, and she doesn't know which of them will be successful, every single company she invests in must be capable of generating something like a 42-time return.

Let's consider what this scenario looks like from the company's point of view. An investor return of $4.2 million doesn't represent the value of the entire company. If we assume that Melanie invested in the seed round, and the company then raised money from other investors, her shareholding will have been diluted. It might have gone from 10 percent at the seed round to 2 percent on exit.

If 2 percent of the company is worth $4.2 million, the entire company must be worth $210 million on exit.

As a startup founder, if you're aiming to raise money from investors, you need to see a realistic path to achieve the sort of growth and scale described here for company 10.

Only if you can achieve this goal will investors see your company as a sound investment prospect.

Note

The numbers in this scenario are illustrative. Many variables influence the outcome, such as the total amount of capital raised and the time from seed round to exit.