Understand the Inner Loop

The inner loop is a fundamental concept in software development that significantly impacts developer productivity and feedback cycles. Understanding and optimizing the inner loop is crucial for efficient DevOps practices and continuous improvement.

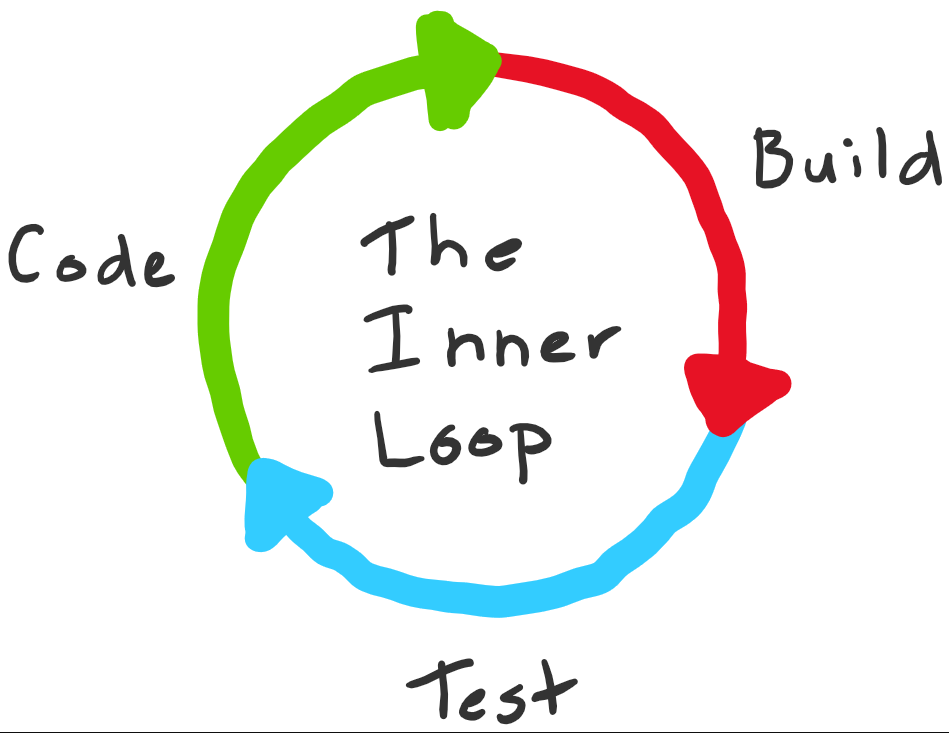

What is the inner loop?

The inner loop is the iterative process that a developer performs when writing, building, and debugging code. It represents the rapid feedback cycle that happens locally on a developer's machine before code is shared with the team or deployed to production.

Key characteristics

- Local execution: Runs entirely on the developer's workstation

- Fast iteration: Designed for quick feedback and rapid changes

- Frequent repetition: Executed many times per day during active development

- Individual focus: Optimized for single-developer productivity

- Pre-commit activities: Happens before code enters version control

Many development teams recognize the inner loop as something they want to keep as short as possible because faster feedback leads to higher productivity and better code quality.

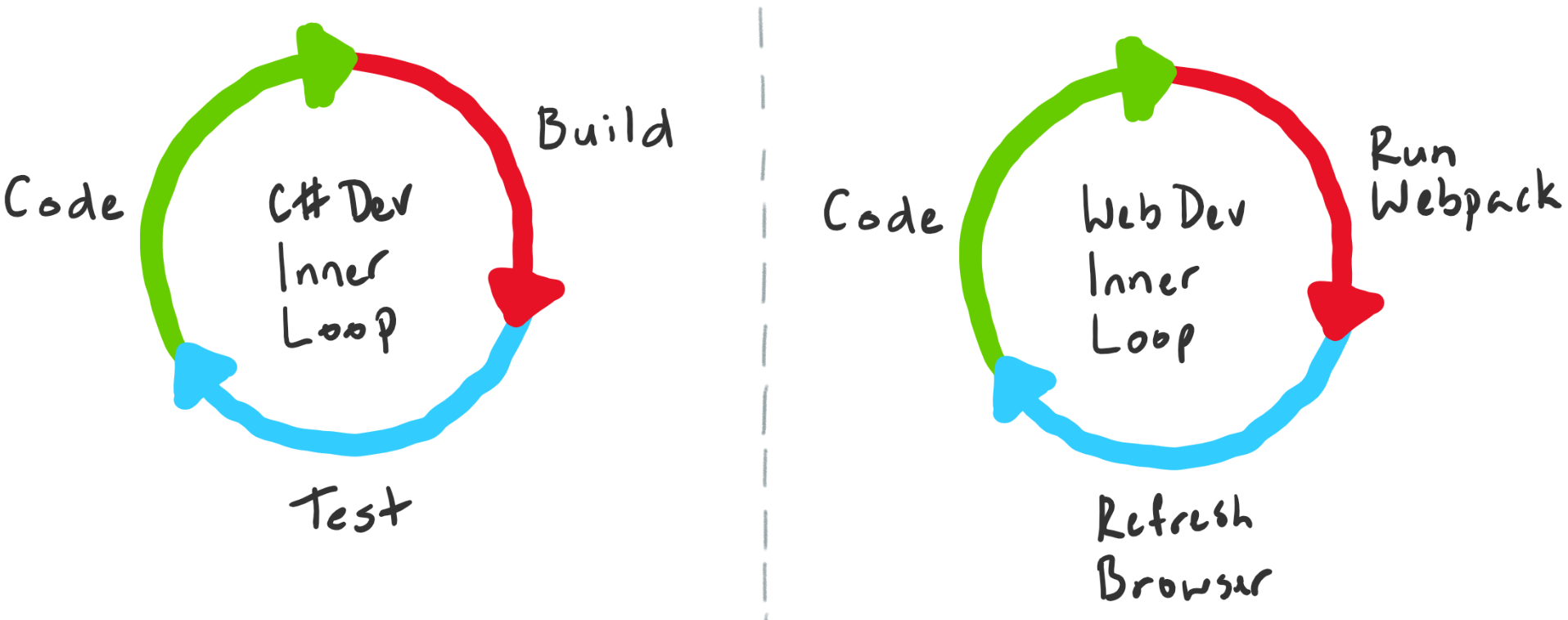

Inner loop variations by technology

The specific activities in a developer's inner loop depend significantly on:

- Technologies used: Programming languages, frameworks, and runtime environments

- Tools available: IDEs, build systems, and testing frameworks

- Developer preferences: Individual workflow optimizations and habits

- Project type: Web applications, libraries, microservices, or mobile apps

Example: Library development inner loop

For library development, a typical inner loop includes:

- Coding: Write or modify library code

- Building: Compile the library

- Testing: Run unit tests to verify functionality

- Debugging: Fix issues discovered during testing

- Committing: Save changes to local Git repository

Example: Web front-end development inner loop

For web front-end work, the inner loop is optimized differently:

- Coding: Edit HTML, CSS, and JavaScript

- Bundling: Run build tools (Webpack, Vite, etc.)

- Refreshing: Reload browser to see changes

- Debugging: Use browser DevTools to inspect behavior

- Committing: Save changes to local Git repository

Contextual switching

Most modern codebases comprise multiple components, so a developer's inner loop may alternate depending on what is being worked on:

- Backend API: Focus on code, build, test, debug

- Frontend UI: Focus on code, bundle, refresh, inspect

- Database schema: Focus on migrations, testing, rollback

- Infrastructure: Focus on configuration, deployment, validation

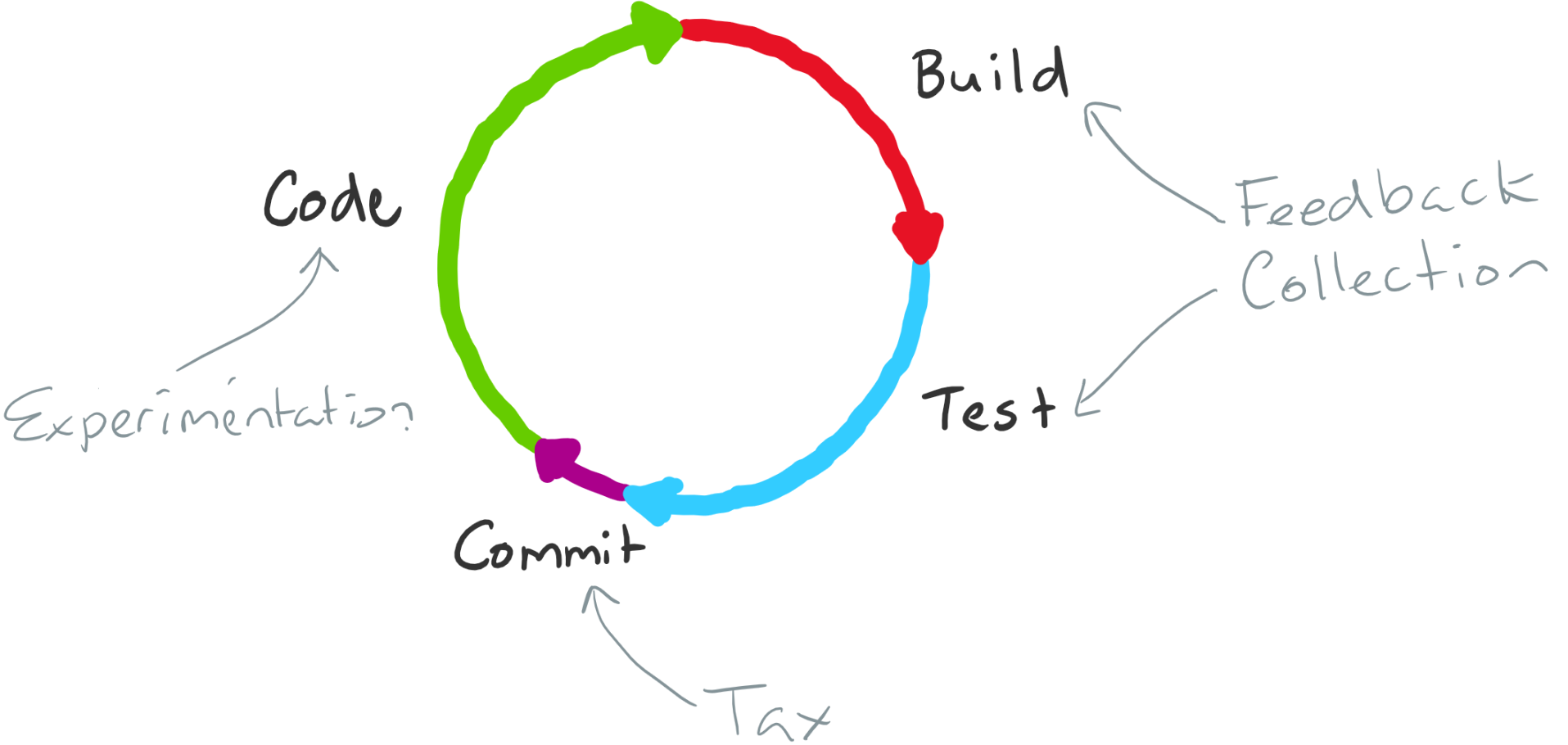

Categorizing inner loop activities

The steps within the inner loop can be grouped into three broad activity categories:

1. Experimentation

Activities that add customer value:

- Coding: Writing new features or fixing bugs

- Designing: Planning architecture or user interfaces

- Prototyping: Exploring new approaches or solutions

Characteristic: These activities are the only ones that directly add value to the end product.

2. Feedback collection

Activities that verify quality:

- Building: Compiling code to verify syntax and dependencies

- Testing: Running unit tests to validate functionality

- Debugging: Identifying and fixing issues

- Code analysis: Running linters and static analyzers

Characteristic: These activities don't add value directly but provide essential feedback to ensure code quality and correctness.

3. Tax

Activities that are necessary but don't add value or feedback:

- Committing: Saving code to version control

- Configuration: Setting up build environments

- Synchronization: Pulling latest changes from remote repositories

- Documentation updates: Updating README files or comments

Characteristic: These activities are necessary work but neither add customer value nor provide feedback. If an activity is unnecessary, it's waste and should be eliminated.

Example categorization: Library development

For the library development scenario:

| Activity | Category | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Coding | Experimentation | Adds customer value |

| Building | Feedback Collection | Verifies code compiles |

| Testing / Debugging | Feedback Collection | Validates functionality |

| Committing | Tax | Necessary but adds no value |

Note

Putting committing in the tax category may seem harsh, but the categorization helps identify activities that should be minimized or deferred until absolutely necessary.

Optimizing the inner loop

Having categorized the steps within the loop, it's now possible to establish optimization principles:

Core optimization principles

1. Speed is proportional to change

- Goal: Execute the loop as fast as possible

- Principle: Total execution time should be proportional to the size of changes made

- Benefit: Small changes get quick feedback; large changes take appropriately longer

2. Maximize feedback quality, minimize feedback time

- Goal: Get the most useful information in the shortest time

- Principle: Balance between comprehensive testing and rapid iteration

- Benefit: Catch critical issues quickly while deferring less critical checks

3. Minimize or defer tax

- Goal: Reduce unnecessary overhead

- Principle: Eliminate waste and defer non-critical activities

- Example: Defer documentation updates until commit time

4. Combat complexity growth

- Challenge: As codebases grow, inner loops naturally slow down

- Reason: More code means more tests, dependencies, and build time

- Impact: Even small changes require disproportionate feedback collection time

The monolithic codebase problem

In large monolithic codebases, you can encounter situations where:

- Small change: Modify one function

- Disproportionate cost: Wait 10+ minutes for full build and test suite

- Developer frustration: Productivity plummets as feedback cycles slow

- Context switching: Developers lose focus waiting for builds

This is a problem you must address proactively.

Strategies for large codebase optimization

Teams can employ several strategies to optimize the inner loop for larger codebases:

1. Incremental builds and tests

Only build and test what changed:

- Smart build systems: Detect changed files and rebuild only affected components

- Test selection: Run only tests affected by code changes

- Dependency tracking: Understand which tests depend on which code

- Tools: Use build systems like Bazel, Buck, or Gradle with smart incremental builds

Benefits:

- Dramatically reduced build times for small changes

- Proportional feedback time to change size

- Faster iteration cycles

2. Caching intermediate results

Cache build artifacts to speed up complete builds:

- Local caching: Store compiled objects and test results locally

- Distributed caching: Share build artifacts across team members

- Remote execution: Offload compilation to cloud build farms

- Tools: Implement caching with systems like ccache, sccache, or cloud-based solutions

Benefits:

- Avoid redundant compilation of unchanged code

- Faster clean builds after branch switches

- Reduced CI/CD pipeline execution time

3. Modularization and binary sharing

Break up the codebase into small units and share binaries:

- Extract libraries: Pull common functionality into separate packages

- Define boundaries: Create clear module interfaces and dependencies

- Version packages: Publish stable versions of internal libraries

- Manage dependencies: Use package managers to consume stable versions

Caution: This strategy can be a double-edged sword if done incorrectly (see Tangled Loops section below).

Benefits when done right:

- Smaller compilation units

- Independent versioning and deployment

- Clearer architectural boundaries

- Reusable components across projects

Risks when done wrong:

- Tangled dependencies requiring changes across multiple repositories

- Increased tax due to outer loop overhead

- Version mismatch problems

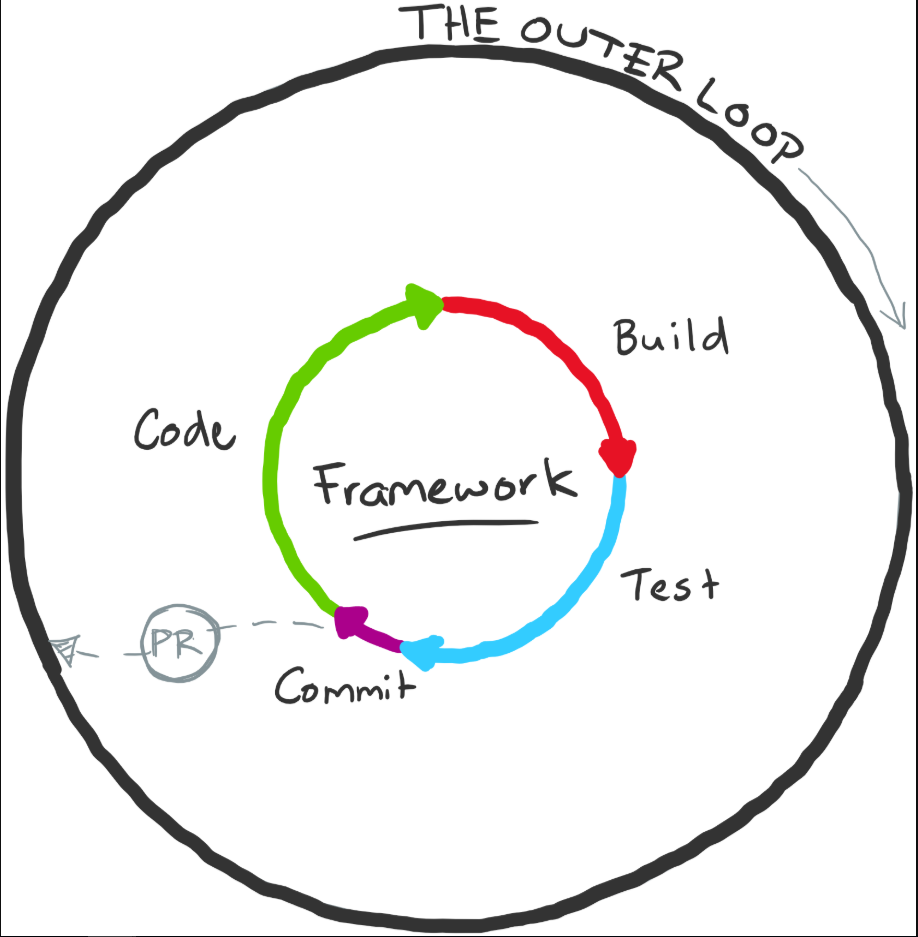

Understanding tangled loops

The concept of tangled loops illustrates what happens when modularization is done incorrectly, causing inner and outer loops to become entangled.

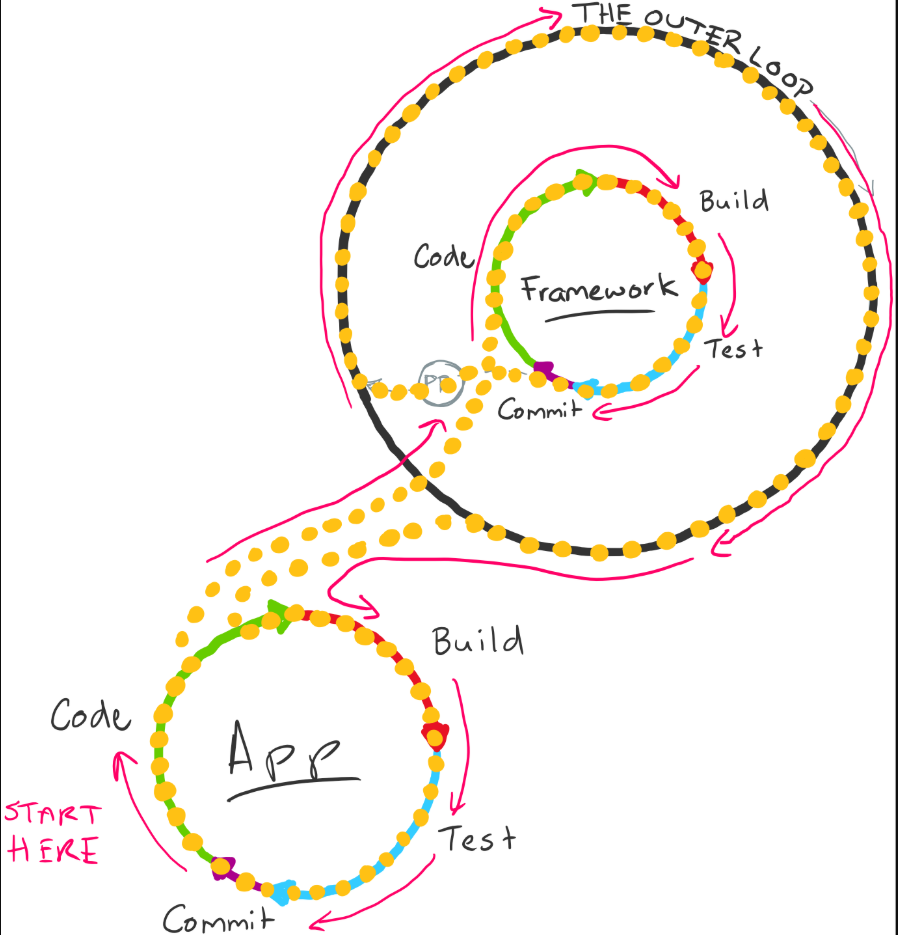

The outer loop

Before understanding tangled loops, we need to define the outer loop:

Outer loop characteristics:

- Team collaboration: Code is shared with the team through pull requests

- Quality gates: Code reviews, automated scans, security checks

- Integration: Code is merged into main branch and deployed

- Higher tax: More overhead due to collaboration and automation

- Slower feedback: Minutes to hours instead of seconds to minutes

The modularization scenario

Consider this common scenario:

Initial state: A monolithic application with an application-specific framework that does heavy lifting.

Modularization decision: Extract the framework into a separate package.

Implementation steps:

- Pull code into separate repository: Framework code moves to its own repo

- Set up CI/CD pipeline: Automated build and publish for framework package

- Add quality gates: Pull request reviews, security scans, approval workflows

- Publish as package: Framework becomes a versioned dependency

Initial result: Things work well initially. The monolith consumes stable framework versions.

When tangling occurs

Problem scenario: You need to develop a new feature that requires extensive new capabilities in the framework.

The pain point: You must now co-evolve code in two separate repositories with a binary dependency between them.

What happens:

- Add method to framework: Create new capability in framework repo

- Go through outer loop: Code review, tests, security scans, approval

- Wait for package publish: Framework package must be built and published

- Update application: Modify application to use new framework method

- Repeat: Every iteration requires full outer loop cycle

The problem: The original codebase's inner loop now includes the outer loop of the framework code.

Outer loop tax

The outer loop includes significant tax:

- Code reviews: Wait for reviewers to provide feedback

- Security scanning: Automated vulnerability and compliance checks

- Binary signing: Certificate-based signing for published packages

- Release pipelines: Deployment automation and testing

- Approval gates: Manual approvals for production releases

Impact: You don't want to pay this tax every time you add a method to a class and want to use it immediately.

Developer workarounds

What typically happens:

Local hacks: Developers create workarounds to stitch inner loops together:

- Local package references: Point to local filesystem instead of published package

- Git submodules: Include framework source directly in application

- Sym links: Create links between repositories

- Pre-release packages: Publish to test feeds

Consequence: These workarounds get messy quickly and still require paying outer loop tax eventually.

The right way to modularize

Modularization isn't inherently bad - it can work brilliantly when done correctly:

Good modularization:

- Stable interfaces: Framework APIs change infrequently

- Independent evolution: Framework and application evolve separately

- Clear boundaries: Well-defined responsibilities and contracts

- Loose coupling: Minimal dependencies between components

Bad modularization:

- Tight coupling: Framework and application must change together

- Frequent co-evolution: Every feature requires framework changes

- Unclear boundaries: Responsibilities overlap between components

- Artificial separation: Split made for organizational, not technical reasons

Key principle: Make modularization incisions carefully based on actual architectural boundaries, not organizational structure.

Best practices for inner loop optimization

Monitor and measure

Track inner loop metrics:

- Build time: How long does compilation take?

- Test execution time: How long do tests run?

- Feedback delay: Time from save to seeing results

- Developer satisfaction: Survey team about pain points

Tools for measurement:

- Build system analytics

- IDE performance profilers

- Test execution reports

- Developer productivity surveys

Address slowdowns proactively

Warning signs:

- Developers complain about slow builds

- Context switching increases during build waits

- Team starts skipping tests locally

- Pull requests include "untested" code

Response strategies:

- Investigate root causes immediately

- Prioritize optimization work

- Involve entire team in solutions

- Measure improvements over time

Balance trade-offs

Key trade-offs to consider:

| Optimization | Benefit | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Incremental builds | Faster local builds | Complex build configuration |

| Build caching | Faster clean builds | Storage and network overhead |

| Modularization | Smaller compilation units | Potential tangled loops |

| Fewer tests | Faster feedback | Reduced confidence |

| Parallel execution | Faster overall time | Higher resource usage |

Principle: Improving one aspect will often cause issues in another. Continuously evaluate trade-offs.

Team alignment

Shared responsibility:

- Architects: Design for testability and modularity

- Developers: Write efficient tests and avoid unnecessary dependencies

- DevOps: Provide build infrastructure and caching

- Management: Prioritize inner loop optimization work

Cultural practices:

- Treat inner loop time as a key productivity metric

- Make "slow build" a valid reason to pause feature work

- Celebrate inner loop improvements

- Share optimization knowledge across teams

Key takeaways

Remember these principles:

- No silver bullet: There's no universal solution for inner loop optimization

- Understand the problem: Identify when slowdowns occur and their root causes

- Measure everything: Track metrics to understand impact of changes

- Act proactively: Address issues before they severely impact productivity

- Balance trade-offs: Every optimization has costs; choose wisely

- Modularize carefully: Split codebases based on technical boundaries, not convenience

- Continuous improvement: Inner loop optimization is ongoing work

Architecture matters: Decisions about how you build, test, and debug your applications will significantly impact developer productivity and happiness. Invest time in getting these fundamentals right.