Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

The Windows security model is based on securable objects. Each component of the operating system must ensure the security of the objects for which it is responsible. Drivers, therefore, must safeguard the security of their devices and device objects.

This topic summarizes how the Windows security model applies to kernel-mode drivers.

Windows security model

The Windows security model is based primarily on per-object rights, with a small number of system-wide privileges. Objects that can be secured include, —but are not limited to, —processes, threads, events and other synchronization objects, as well as files, directories, and devices.

For each type of object, the generic read, write, and execute rights map into detailed object-specific rights. For example, for files and directories, possible rights include the right to read or write the file or directory, the right to read or write extended file attributes, the right to traverse a directory, and the right to write an object’s security descriptor.

The security model involves the following concepts:

- Security identifiers (SIDs)

- Access tokens

- Security descriptors

- Access Control Lists (ACLs)

- Privileges

Security Identifiers (SIDs)

A security identifier (SID, also called a principal) identifies a user, a group, or a logon session. Each user has a unique SID, which is retrieved by the operating system at logon.

SIDs are issued by an authority such as the operating system or a domain server. Some SIDs are well-known and have names as well as identifiers. For example, the SID S-1-1-0 identifies Everyone (or World).

Access tokens

Every process has an access token. The access token describes the complete security context of the process. It contains the SID of the user, the SID of the groups to which the user belongs, and the SID of the logon session, as well as a list of the system-wide privileges granted to the user.

By default, the system uses the primary access token for a process whenever a thread of the process interacts with a securable object. However, a thread can impersonate a client account. When a thread impersonates, it has an impersonation token in addition to its own primary token. The impersonation token describes the security context of the user account that the thread is impersonating. Impersonation is especially common in Remote Procedure Call (RPC) handling.

An access token that describes a restricted security context for a thread or process is called a restricted token. The SIDs in a restricted token can be set only to deny access, not to allow access, to securable objects. In addition, the token can describe a limited set of system-wide privileges. The user’s SID and identity remain the same, but the user’s access rights are limited while the process is using the restricted token. The CreateRestrictedToken function creates a restricted token.

Security descriptors

Every named Windows object has a security descriptor; some unnamed objects do, too. The security descriptor describes the owner and group SIDs for the object along with its ACLs.

An object’s security descriptor is usually created by the function that creates the object. When a driver calls the IoCreateDevice or IoCreateDeviceSecure routine to create a device object, the system applies a security descriptor to the created device object and sets ACLs for the object. For most devices, ACLs are specified in the device Information (INF) file.

For more information Security Descriptors in the kernel driver documentation.

Access Control Lists

Access Control Lists (ACLs) enable fine-grained control over access to objects. An ACL is part of the security descriptor for each object.

Each ACL contains zero or more Access Control Entries (ACE). Each ACE, in turn, contains a single SID that identifies a user, group, or computer and a list of rights that are denied or allowed for that SID.

ACLs for device objects

The ACL for a device object can be set in any of three ways:

- Set in the default security descriptor for its device type.

- Created programmatically by the RtlCreateSecurityDescriptor function and set by the RtlSetDaclSecurityDescriptor function.

- Specified in Security Descriptor Definition Language (SDDL) in the device’s INF file or in a call to the IoCreateDeviceSecure routine.

All drivers should use SDDL in the INF file to specify ACLs for their device objects.

SDDL is an extensible description language that enables components to create ACLs in a string format. SDDL is used by both user-mode and kernel-mode code. The following figure shows the format of SDDL strings for device objects.

The Access value specifies the type of access allowed. The SID value specifies a security identifier that determines to whom the Access value applies (for example, a user or group).

For example, the following SDDL string allows the System (SY) access to everything and allows everyone else (WD) only read access:

“D:P(A;;GA;;;SY)(A;;GR;;;WD)”

The header file wdmsec.h also includes a set of predefined SDDL strings that are suitable for device objects. For example, the header file defines SDDL_DEVOBJ_SYS_ALL_ADM_RWX_WORLD_RWX_RES_RWX as follows:

"D:P(A;;GA;;;SY)(A;;GRGWGX;;;BA)(A;;GRGWGX;;;WD)(A;;GRGWGX;;;RC)"

The first segment of this string allows the kernel and operating system (SY) complete control over the device. The second segment allows anyone in the built-in Administrators group (BA) to access the entire device, but not to change the ACL. The third segment allows everyone (WD) to read or write to the device, and the fourth segment grants the same rights to untrusted code (RC). Drivers can use the predefined strings as is or as models for device-object-specific strings.

All device objects in a stack should have the same ACLs. Changing the ACLs on one device object in the stack changes the ACLs on the entire device stack.

However, adding a new device object to the stack does not change any ACLs, either those of the new device object (if it has ACLs) or those of any existing device objects in the stack. When a driver creates a new device object and attaches it to the top of the stack, the driver should copy the ACLs for the stack to the new device object by copying the DeviceObject.Characteristics field from the next lower driver.

The IoCreateDeviceSecure routine supports a subset of SDDL strings that use predefined SIDs such as WD and SY. User-mode APIs and INF files support the full SDDL syntax.

Security checks using ACLs

When a process requests access to an object, security checks compare the ACLs for the object against the SIDs in the caller’s access token.

The system compares the ACEs in a strict top-down order and stops on the first relevant match. Therefore, when creating an ACL, you should always put denial ACEs above the corresponding grant ACEs. The following examples show how the comparison proceeds.

Example 1: Comparing an ACL to an access token

Example 1 shows how the system compares an ACL to the access token for a caller’s process. Assume that the caller wants to open a file that has the ACL that is shown in the following table.

Sample File ACL

| Permission | SID | Access |

|---|---|---|

| Allow | Accounting | Write, delete |

| Allow | Sales | Append |

| Deny | Legal | Append, write, delete |

| Allow | Everyone | Read |

This ACL has four ACEs, which apply specifically to the Accounting, Sales, Legal, and Everyone groups.

Next, assume the access token for the requesting process contains SIDs for one user and three groups, in the following order:

User Jim (S-1-5-21…)

Group Accounting (S-1-5-22…)

Group Legal (S-1-5-23…)

Group Everyone (S-1-1-0)

When comparing a file ACL to an access token, the system first looks for an ACE for user Jim in the file’s ACL. None appears, so next it looks for an ACE for the Accounting group. As shown in the previous table, an ACE for the Accounting group appears as the first entry in the file’s ACL, so Jim’s process is granted the right to write or delete the file and the comparison stops. If the ACE for the Legal group instead preceded the ACE for the Accounting group in the ACL, the process would be denied write, append, and delete access to the file.

Example 2: Comparing an ACL to a restricted token

The system compares an ACL to a restricted token in the same way that it compares those in a token that is not restricted. However, a denial SID in a restricted token can match only a Deny ACE in an ACL.

Example 2 shows how the system compares a file’s ACL with a restricted token. Assume the file has the same ACL shown in the previous table. In this example, however, the process has a restricted token that contains the following SIDs:

User Jim (S-1-5-21…) Deny

Group Accounting (S-1-5-22…) Deny

Group Legal (S-1-5-23…) Deny

Group Everyone (S-1-1-0)

The file’s ACL does not list Jim’s SID, so the system proceeds to the Accounting group SID. Although the file’s ACL has an ACE for the Accounting group, this ACE allows access; therefore, it does not match the SID in the process’s restricted token, which denies access. As a result, the system proceeds to the Legal group SID. The ACL for the file contains an ACE for the Legal group that denies access, so the process cannot write, append, or delete the file.

Privileges

A privilege is the right for a user to perform a system-related operation on the local computer, such as loading a driver, changing the time, or shutting down the system.

Privileges are different from access rights because they apply to system-related tasks and resources rather than objects, and because they are assigned to a user or group by a system administrator, rather than by the operating system.

The access token for each process contains a list of the privileges granted to the process. Privileges must be specifically enabled before use. For more information on privileges, see Privileges in the kernel driver documentation.

Security related debugger commands

The !acl extension formats and displays the contents of an access control list (ACL). For more information, see Determining the ACL of an Object and !acl.

The !token extension displays a formatted view of a security token object. For more information, see !token.

The !tokenfields extension displays the names and offsets of the fields within the access token object (the TOKEN structure). For more information, see !tokenfields.

The !sid extension displays the security identifier (SID) at the specified address. For more information, see !sid.

The !sd extension displays the security descriptor at the specified address. For more information, see !sd.

Windows security model scenario: Creating a file

The system uses the security constructs described in the Windows security model whenever a process creates a handle to a file or object.

The following diagram shows the security-related actions that are triggered when a user-mode process attempts to create a file.

The previous diagram shows how the system responds when a user-mode application calls the CreateFile function. The following notes refer to the circled numbers in the figure:

- A user-mode application calls the CreateFile function, passing a valid Microsoft Win32 file name.

- The user-mode Kernel32.dll passes the request to Ntdll.dll, which converts the Win32 name to a Microsoft Windows NT file name.

- Ntdll.dll calls the NtCreateFile function with the Windows file name. Within Ntoskrnl.exe, the I/O Manager handles NtCreateFile.

- The I/O Manager repackages the request into an Object Manager call.

- The Object Manager resolves symbolic links and ensures that the user has traversal rights for the path in which the file will be created. For more information, see Security checks in the Object Manager.

- The Object Manager calls the system component that owns the underlying object type associated with the request. For a file creation request, this component is the I/O Manager, which owns device objects.

- The I/O Manager checks the security descriptor for the device object against the access token for the user’s process to ensure that the user has the required access to the device. For more information, see Security checks in the I/O Manager.

- If the user process has the required access, the I/O Manager creates a handle and sends an IRP_MJ_CREATE request to the driver for the device or file system.

- The driver performs additional security checks as needed. For example, if the request specifies an object in the device’s namespace, the driver must ensure that the caller has the required access rights. For more information, see Security checks in the driver.

Security checks in the Object Manager

The responsibility for checking access rights belongs to the highest-level component that can perform such checks. If the Object Manager can verify the caller’s access rights, it does so. If not, the Object Manager passes the request to the component responsible for the underlying object type. That component, in turn, verifies access, if it can; if it cannot, it passes the request to a still-lower component, such as a driver.

The Object Manager checks ACLs for simple object types, such as events and mutex locks. For objects that have a namespace, the type owner performs security checks. For example, the I/O Manager is considered the type owner for device objects and file objects. If the Object Manager finds the name of a device object or file object when parsing a name, it hands off the name to the I/O Manager, as in the file creation scenario presented above. The I/O Manager then checks the access rights if it can. If the name specifies an object within a device namespace, the I/O Manager in turn hands off the name to the device (or file system) driver, and that driver is responsible for validating the requested access.

Security checks in the I/O Manager

When the I/O Manager creates a handle, it checks the object’s rights against the process access token and then stores the rights granted to the user along with the handle. When later I/O requests arrive, the I/O Manager checks the rights associated with the handle to ensure that the process has the right to perform the requested I/O operation. For example, if the process later requests a write operation, the I/O Manager checks the rights associated with the handle to ensure that the caller has write access to the object.

If the handle is duplicated, rights can be removed from the copy, but not added to it.

When the I/O Manager creates an object, it converts generic Win32 access modes to object-specific rights. For example, the following rights apply to files and directories:

| Win32 access mode | Object-specific rights |

|---|---|

| GENERIC_READ | ReadData |

| GENERIC_WRITE | WriteData |

| GENERIC_EXECUTE | ReadAttributes |

| GENERIC_ALL | All |

To create a file, a process must have traversal rights to the parent directories in the target path. For example, to create \Device\CDROM0\Directory\File.txt, a process must have the right to traverse \Device, \Device\CDROM0, and \Device\CDROM0\Directory. The I/O Manager checks only the traversal rights for these directories.

The I/O Manager checks traversal rights when it parses the file name. If the file name is a symbolic link, the I/O Manager resolves it to a full path and then checks traversal rights, starting from the root. For example, assume the symbolic link \DosDevices\D maps to the Windows NT device name \Device\CDROM0. The process must have traversal rights to the \Device directory.

For more information, see Object Handles and Object Security.

Security checks in the driver

The operating system kernel treats every driver, in effect, as a file system with its own namespace. Consequently, when a caller attempts to create an object in the device namespace, the I/O Manager checks that the process has traversal rights to the directories in the path.

With WDM drivers, the I/O Manager does not perform security checks against the namespace, unless the Device Object has been created specifying FILE_DEVICE_SECURE_OPEN. When FILE_DEVICE_SECURE_OPEN is not set, the driver is responsible for ensuring the security of its namespace. For more information, see Controlling Device Namespace Access and Securing Device Objects.

For WDF drivers, the FILE_DEVICE_SECURE_OPEN flag is always set, so that there will be a check of the device's security descriptor before allowing an application to access any names within the device's namespace. For more information, see Controlling Device Access in KMDF Drivers.

Windows security boundaries

Drivers communicating with each other and to user mode callers of different privilege levels can be considered to be crossing a trust boundary. A trust boundary is any code execution path that crosses from a lower privileged process into a higher privileged process.

The higher the disparity in the privilege levels, the more interesting the boundary is for attackers that want to perform attacks such as a privilege escalation attack against the targeted driver or process.

Part of the process of creating a threat model is to examine the security boundaries and look for unanticipated paths. For more information, see Threat modeling for drivers.

Any data that crosses a trust boundary is untrusted and must be validated.

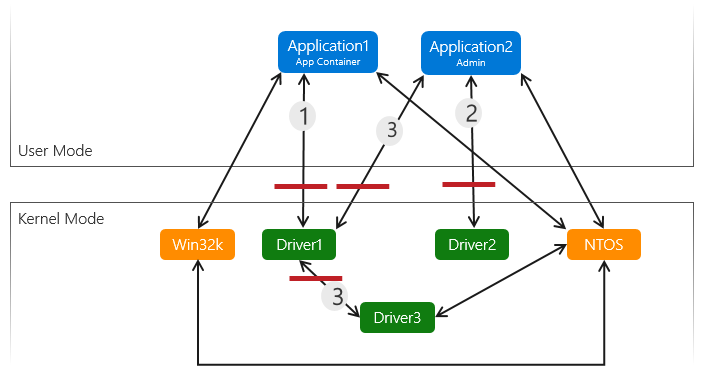

This diagram shows three kernel drivers, and two apps, one in an app container and one app that runs with admin rights. The red lines indicate example trust boundaries.

As the app container can provide additional constraints, and is not running at admin level, path (1) is a higher risk path for an escalation attack since the trust boundary is between an app container ( a very low privilege process) and a kernel driver.

Path (2) is a lower risk path, as the app is running with admin rights and is calling directly into the kernel driver. Admin is already a fairly high privilege on the system so the attack surface from admin to kernel is less of an interesting target to attackers, but still a noteworthy trust boundary.

Path (3) is an example of a code execution path that crosses multiple trust boundaries that could be missed if a threat model is not created. In this example, there is a trust boundary between driver 1 and driver 3, as driver 1 takes input from the user mode app and passes it directly to driver 3.

All inputs coming into the driver from user mode is untrusted and should be validated. Inputs coming from other drivers may also be untrusted depending on whether the previous driver was just a simple pass-through (e.g. data was received by driver 1 from app 1 , driver 1 didn’t do any validation on the data and just passed it forward to driver 3). Be sure to identify all attack surfaces and trust boundaries and validate all data crossing them, by creating a complete threat model.

Windows Security Model Recommendations

- Set strong default ACLs in calls to the IoCreateDeviceSecure routine.

- Specify ACLs in the INF file for each device. These ACLs can loosen tight default ACLs if necessary.

- Set the FILE_DEVICE_SECURE_OPEN characteristic to apply device object security settings to the device namespace.

- Do not define IOCTLs that permit FILE_ANY_ACCESS unless such access cannot be exploited maliciously.

- Use the IoValidateDeviceIoControlAccess routine to tighten security on existing IOCTLS that allow FILE_ANY_ACCESS.

- Create a threat model to examine the security boundaries and look for unanticipated paths. For more information, see Threat modeling for drivers.

- See Driver security checklist for additional driver security recommendations.