Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

Any driver can use a semaphore object to synchronize operations between its driver-created threads and other driver routines. For example, a driver-dedicated thread might put itself into a wait state when there are no outstanding I/O requests for the driver, and the driver's dispatch routines might set the semaphore to the Signaled state just after they queue an IRP.

The dispatch routines of highest-level drivers, which are run in the context of the thread requesting an I/O operation, might use a semaphore to protect a resource shared among the dispatch routines. Lower-level driver dispatch routines for synchronous I/O operations also might use a semaphore to protect a resource shared among that subset of dispatch routines or with a driver-created thread.

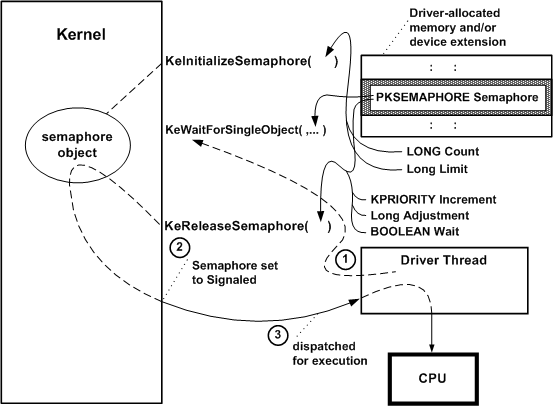

Any driver that uses a semaphore object must call KeInitializeSemaphore before it waits on or releases the semaphore. The following figure illustrates how a driver with a thread can use a semaphore object.

As the previous figure shows, such a driver must provide the storage for the semaphore object, which should be resident. The driver can use the device extension of a driver-created device object, the controller extension if it uses a controller object, or nonpaged pool allocated by the driver.

When the driver's AddDevice routine calls KeInitializeSemaphore, it must pass a pointer to the driver's resident storage for the semaphore object. In addition, the caller must specify a Count for the semaphore object, as shown in the previous figure, that determines its initial state (nonzero for Signaled).

The caller also must specify a Limit for the semaphore, which can be either of the following:

Limit = 1

When this semaphore is set to the Signaled state, a single thread waiting for the semaphore to be set to the Signaled state becomes eligible for execution and can access whatever resource is protected by the semaphore.

This type of semaphore is also called a binary semaphore because a thread either has or does not have exclusive access to the semaphore-protected resource.

Limit > 1

When this semaphore is set to the Signaled state, some number of threads waiting for the semaphore object to be set to the Signaled state become eligible for execution and can access whatever resource is protected by the semaphore.

This type of semaphore is called a counting semaphore because the routine that sets the semaphore to the Signaled state also specifies how many waiting threads can have their states changed from waiting to ready. The number of such waiting threads can be the Limit set when the semaphore was initialized or some number less than this preset Limit.

Few device or intermediate drivers have a single driver-created thread; even fewer have a set of threads that might wait for a semaphore to be acquired or released. Few system-supplied drivers use semaphore objects, and, of those that do, even fewer use a binary semaphore. Although a binary semaphore might seem to be similar in functionality to a mutex object, a binary semaphore does not provide the built-in protection against deadlocks that a mutex object has for system threads running in SMP machines.

After a driver with an initialized semaphore is loaded, it can synchronize operations on the semaphore that protects a shared resource. For example, a driver with a device-dedicated thread that manages the queuing of IRPs, such as the system floppy controller driver, might synchronize IRP queuing on a semaphore, as shown in the previous figure:

The thread calls KeWaitForSingleObject with a pointer to the driver-supplied storage for the initialized semaphore object to put itself into a wait state.

IRPs begin to come in that require device I/O operations. The driver's dispatch routines insert each such IRP into an interlocked queue under spin-lock control and call KeReleaseSemaphore with a pointer to the semaphore object, a driver-determined priority boost for the thread (Increment, as shown in the previous figure), an Adjustment of 1 that is added to the semaphore's Count as each IRP is queued, and a Boolean Wait set to FALSE. A nonzero semaphore Count sets the semaphore object to the Signaled state, thereby changing the waiting thread's state to ready.

The kernel dispatches the thread for execution as soon as a processor is available: that is, no other thread with a higher priority is currently in the ready state and there are no kernel-mode routines to be run at a higher IRQL.

The thread removes an IRP from the interlocked queue under spin-lock control, passes it on to other driver routines for further processing, and calls KeWaitForSingleObject again. If the semaphore is still set to the Signaled state (that is, its Count remains nonzero, indicating that more IRPs are in the driver's interlocked queue), the kernel again changes the thread's state from waiting to ready.

By using a counting semaphore in this manner, such a driver thread "knows" there is an IRP to be removed from the interlocked queue whenever that thread is run.

For info specific to managing IRQL when calling KeReleaseSemaphore, see the Remarks section of KeReleaseSemaphore.

Any standard driver routine that runs at an IRQL greater than PASSIVE_LEVEL cannot wait for a nonzero interval on any dispatcher objects without bringing down the system; see Kernel Dispatcher Objects for details. However, such a routine can call KeReleaseSemaphore while running at an IRQL less than or equal to DISPATCH_LEVEL.

For a summary of the IRQLs at which standard driver routines run, see Managing Hardware Priorities. For IRQL requirements of a specific support routine, see the routine's reference page.