Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

This topic shows how to consume C++/WinRT APIs, whether they're part of Windows, implemented by a third-party component vendor, or implemented by yourself.

Important

So that the code examples in this topic are short, and easy for you to try out, you can reproduce them by creating a new Windows Console Application (C++/WinRT) project, and copy-pasting code. However, you can't consume arbitrary custom (third-party) Windows Runtime types from an unpackaged app like that. You can consume only Windows types that way.

To consume custom (third-party) Windows Runtime types from a console app, you'll need to give the app a package identity so that it can resolve the consumed custom types' registration. For more info, see Windows Application Packaging Project.

Alternatively, create a new project from the Blank App (C++/WinRT), Core App (C++/WinRT), or Windows Runtime Component (C++/WinRT) project templates. Those app types already have a package identity.

If the API is in a Windows namespace

This is the most common case in which you'll consume a Windows Runtime API. For every type in a Windows namespace defined in metadata, C++/WinRT defines a C++-friendly equivalent (called the projected type). A projected type has the same fully-qualified name as the Windows type, but it's placed in the C++ winrt namespace using C++ syntax. For example, Windows::Foundation::Uri is projected into C++/WinRT as winrt::Windows::Foundation::Uri.

Here's a simple code example. If you want to copy-paste the following code examples directly into the main source code file of a Windows Console Application (C++/WinRT) project, then first set Not Using Precompiled Headers in project properties.

// main.cpp

#include <winrt/Windows.Foundation.h>

using namespace winrt;

using namespace Windows::Foundation;

int main()

{

winrt::init_apartment();

Uri contosoUri{ L"http://www.contoso.com" };

Uri combinedUri = contosoUri.CombineUri(L"products");

}

The included header winrt/Windows.Foundation.h is part of the SDK, found inside the folder %WindowsSdkDir%Include<WindowsTargetPlatformVersion>\cppwinrt\winrt\. The headers in that folder contain Windows namespace types projected into C++/WinRT. In this example, winrt/Windows.Foundation.h contains winrt::Windows::Foundation::Uri, which is the projected type for the runtime class Windows::Foundation::Uri.

Tip

Whenever you want to use a type from a Windows namespace, include the C++/WinRT header corresponding to that namespace. The using namespace directives are optional, but convenient.

In the code example above, after initializing C++/WinRT, we stack-allocate a value of the winrt::Windows::Foundation::Uri projected type via one of its publicly documented constructors (Uri(String), in this example). For this, the most common use case, that's typically all you have to do. Once you have a C++/WinRT projected type value, you can treat it as if it were an instance of the actual Windows Runtime type, since it has all the same members.

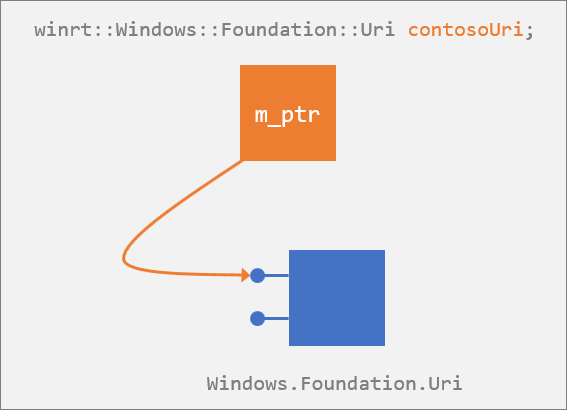

In fact, that projected value is a proxy; it's essentially just a smart pointer to a backing object. The projected value's constructor(s) call RoActivateInstance to create an instance of the backing Windows Runtime class (Windows.Foundation.Uri, in this case), and store that object's default interface inside the new projected value. As illustrated below, your calls to the projected value's members actually delegate, via the smart pointer, to the backing object; which is where state changes occur.

When the contosoUri value falls out of scope, it destructs, and releases its reference to the default interface. If that reference is the last reference to the backing Windows Runtime Windows.Foundation.Uri object, the backing object destructs as well.

Tip

A projected type is a wrapper over a Windows Runtime type for purposes of consuming its APIs. For example, a projected interface is a wrapper over a Windows Runtime interface.

C++/WinRT projection headers

To consume Windows namespace APIs from C++/WinRT, you include headers from the %WindowsSdkDir%Include<WindowsTargetPlatformVersion>\cppwinrt\winrt folder. You must include the headers corresponding to each namespace you use.

For example, for the Windows::Security::Cryptography::Certificates namespace, the equivalent C++/WinRT type definitions reside in winrt/Windows.Security.Cryptography.Certificates.h. Including that header gives you access to all the types in the Windows::Security::Cryptography::Certificates namespace.

Sometimes, one namespace header will include portions of related namespace headers, but you shouldn't rely on this implementation detail. Explicitly include the headers for the namespaces you use.

For example, the Certificate::GetCertificateBlob method returns an

Windows::Storage::Streams::IBuffer interface.

Before calling the Certificate::GetCertificateBlob method,

you must include the winrt/Windows.Storage.Streams.h namespace header file to ensure that you can receive and operate on the returned Windows::Storage::Streams::IBuffer.

Forgetting to include the required namespace headers before using types in that namespace is a common source of build errors.

Accessing members via the object, via an interface, or via the ABI

With the C++/WinRT projection, the runtime representation of a Windows Runtime class is no more than the underlying ABI interfaces. But, for your convenience, you can code against classes in the way that their author intended. For example, you can call the ToString method of a Uri as if that were a method of the class (in fact, under the covers, it's a method on the separate IStringable interface).

WINRT_ASSERT is a macro definition, and it expands to _ASSERTE.

Uri contosoUri{ L"http://www.contoso.com" };

WINRT_ASSERT(contosoUri.ToString() == L"http://www.contoso.com/"); // QueryInterface is called at this point.

This convenience is achieved via a query for the appropriate interface. But you're always in control. You can opt to give away a little of that convenience for a little performance by retrieving the IStringable interface yourself and using it directly. In the code example below, you obtain an actual IStringable interface pointer at run time (via a one-time query). After that, your call to ToString is direct, and avoids any further call to QueryInterface.

...

IStringable stringable = contosoUri; // One-off QueryInterface.

WINRT_ASSERT(stringable.ToString() == L"http://www.contoso.com/");

You might choose this technique if you know you'll be calling several methods on the same interface.

Incidentally, if you do want to access members at the ABI level then you can. The code example below shows how, and there are more details and code examples in Interop between C++/WinRT and the ABI.

#include <Windows.Foundation.h>

#include <unknwn.h>

#include <winrt/Windows.Foundation.h>

using namespace winrt::Windows::Foundation;

int main()

{

winrt::init_apartment();

Uri contosoUri{ L"http://www.contoso.com" };

int port{ contosoUri.Port() }; // Access the Port "property" accessor via C++/WinRT.

winrt::com_ptr<ABI::Windows::Foundation::IUriRuntimeClass> abiUri{

contosoUri.as<ABI::Windows::Foundation::IUriRuntimeClass>() };

HRESULT hr = abiUri->get_Port(&port); // Access the get_Port ABI function.

}

Delayed initialization

In C++/WinRT, each projected type has a special C++/WinRT std::nullptr_t constructor. With the exception of that one, all projected-type constructors—including the default constructor—cause a backing Windows Runtime object to be created, and give you a smart pointer to it. So, that rule applies anywhere that the default constructor is used, such as uninitialized local variables, uninitialized global variables, and uninitialized member variables.

If, on the other hand, you want to construct a variable of a projected type without it in turn constructing a backing Windows Runtime object (so that you can delay that work until later), then you can do that. Declare your variable or field using that special C++/WinRT std::nullptr_t constructor (which the C++/WinRT projection injects into every runtime class). We use that special constructor with m_gamerPicBuffer in the code example below.

#include <winrt/Windows.Storage.Streams.h>

using namespace winrt::Windows::Storage::Streams;

#define MAX_IMAGE_SIZE 1024

struct Sample

{

void DelayedInit()

{

// Allocate the actual buffer.

m_gamerPicBuffer = Buffer(MAX_IMAGE_SIZE);

}

private:

Buffer m_gamerPicBuffer{ nullptr };

};

int main()

{

winrt::init_apartment();

Sample s;

// ...

s.DelayedInit();

}

All constructors on the projected type except the std::nullptr_t constructor cause a backing Windows Runtime object to be created. The std::nullptr_t constructor is essentially a no-op. It expects the projected object to be initialized at a subsequent time. So, whether a runtime class has a default constructor or not, you can use this technique for efficient delayed initialization.

This consideration affects other places where you're invoking the default constructor, such as in vectors and maps. Consider this code example, for which you'll need a Blank App (C++/WinRT) project.

std::map<int, TextBlock> lookup;

lookup[2] = value;

The assignment creates a new TextBlock, and then immediately overwrites it with value. Here's the remedy.

std::map<int, TextBlock> lookup;

lookup.insert_or_assign(2, value);

Also see How the default constructor affects collections.

Don't delay-initialize by mistake

Be careful that you don't invoke the std::nullptr_t constructor by mistake. The compiler's conflict resolution favors it over the factory constructors. For example, consider these two runtime class definitions.

// GiftBox.idl

runtimeclass GiftBox

{

GiftBox();

}

// Gift.idl

runtimeclass Gift

{

Gift(GiftBox giftBox); // You can create a gift inside a box.

}

Let's say that we want to construct a Gift that isn't inside a box (a Gift that's constructed with an uninitialized GiftBox). First, let's look at the wrong way to do that. We know that there'a Gift constructor that takes a GiftBox. But if we're tempted to pass a null GiftBox (invoking the Gift constructor via uniform initialization, as we do below), then we won't get the result we want.

// These are *not* what you intended. Doing it in one of these two ways

// actually *doesn't* create the intended backing Windows Runtime Gift object;

// only an empty smart pointer.

Gift gift{ nullptr };

auto gift{ Gift(nullptr) };

What you get here is an uninitialized Gift. You don't get a Gift with an uninitialized GiftBox. Here's the correct way to do that.

// Doing it in one of these two ways creates an initialized

// Gift with an uninitialized GiftBox.

Gift gift{ GiftBox{ nullptr } };

auto gift{ Gift(GiftBox{ nullptr }) };

In the incorrect example, passing a nullptr literal resolves in favor of the delay-initializing constructor. To resolve in favor of the factory constructor, the type of the parameter must be a GiftBox. You still have the option to pass an explicitly delay-initializing GiftBox, as shown in the correct example.

This next example is also correct, because the parameter has type GiftBox, and not std::nullptr_t.

GiftBox giftBox{ nullptr };

Gift gift{ giftBox }; // Calls factory constructor.

It's only when you pass a nullptr literal that the ambiguity arises.

Don't copy-construct by mistake.

This caution is similar to the one described in the Don't delay-initialize by mistake section above.

In addition to the delay-initializing constructor, the C++/WinRT projection also injects a copy constructor into every runtime class. It's a single-parameter constructor that accepts the same type as the object being constructed. The resulting smart pointer points to the same backing Windows Runtime object as that pointed to by its constructor parameter. The result is two smart pointer objects pointing to the same backing object.

Here's a runtime class definition that we'll use in the code examples.

// GiftBox.idl

runtimeclass GiftBox

{

GiftBox(GiftBox biggerBox); // You can place a box inside a bigger box.

}

Let's say that we want to construct a GiftBox inside a larger GiftBox.

GiftBox bigBox{ ... };

// These are *not* what you intended. Doing it in one of these two ways

// copies bigBox's backing-object-pointer into smallBox.

// The result is that smallBox == bigBox.

GiftBox smallBox{ bigBox };

auto smallBox{ GiftBox(bigBox) };

The correct way to do it is to call the activation factory explicitly.

GiftBox bigBox{ ... };

// These two ways call the activation factory explicitly.

GiftBox smallBox{

winrt::get_activation_factory<GiftBox, IGiftBoxFactory>().CreateInstance(bigBox) };

auto smallBox{

winrt::get_activation_factory<GiftBox, IGiftBoxFactory>().CreateInstance(bigBox) };

If the API is implemented in a Windows Runtime component

This section applies whether you authored the component yourself, or it came from a vendor.

Note

For info about installing and using the C++/WinRT Visual Studio Extension (VSIX) and the NuGet package (which together provide project template and build support), see Visual Studio support for C++/WinRT.

In your application project, reference the Windows Runtime component's Windows Runtime metadata (.winmd) file, and build. During the build, the cppwinrt.exe tool generates a standard C++ library that fully describes—or projects—the API surface for the component. In other words, the generated library contains the projected types for the component.

Then, just as for a Windows namespace type, you include a header and construct the projected type via one of its constructors. Your application project's startup code registers the runtime class, and the projected type's constructor calls RoActivateInstance to activate the runtime class from the referenced component.

#include <winrt/ThermometerWRC.h>

struct App : implements<App, IFrameworkViewSource, IFrameworkView>

{

ThermometerWRC::Thermometer thermometer;

...

};

For more details, code, and a walkthrough of consuming APIs implemented in a Windows Runtime component, see Windows Runtime components with C++/WinRT and Author events in C++/WinRT.

If the API is implemented in the consuming project

The code example in this section is taken from the topic XAML controls; bind to a C++/WinRT property. See that topic for more details, code, and a walkthrough of consuming a runtime class that's implemented in the same project that consumes it.

A type that's consumed from XAML UI must be a runtime class, even if it's in the same project as the XAML. For this scenario, you generate a projected type from the runtime class's Windows Runtime metadata (.winmd). Again, you include a header, but then you have a choice between the C++/WinRT version 1.0 or version 2.0 ways of constructing the instance of the runtime class. The version 1.0 method uses winrt::make; the version 2.0 method is known as uniform construction. Let's look at each in turn.

Constructing by using winrt::make

Let's start with the default (C++/WinRT version 1.0) method, because it's a good idea to be at least familiar with that pattern. You construct the projected type via its std::nullptr_t constructor. That constructor doesn't perform any initialization, so you must next assign a value to the instance via the winrt::make helper function, passing any necessary constructor arguments. A runtime class implemented in the same project as the consuming code doesn't need to be registered, nor instantiated via Windows Runtime/COM activation.

See XAML controls; bind to a C++/WinRT property for a full walkthrough. This section shows extracts from that walkthrough.

// MainPage.idl

import "BookstoreViewModel.idl";

namespace Bookstore

{

runtimeclass MainPage : Windows.UI.Xaml.Controls.Page

{

BookstoreViewModel MainViewModel{ get; };

}

}

// MainPage.h

...

struct MainPage : MainPageT<MainPage>

{

...

private:

Bookstore::BookstoreViewModel m_mainViewModel{ nullptr };

};

...

// MainPage.cpp

...

#include "BookstoreViewModel.h"

MainPage::MainPage()

{

m_mainViewModel = winrt::make<Bookstore::implementation::BookstoreViewModel>();

...

}

Uniform construction

With C++/WinRT version 2.0 and later, there's an optimized form of construction available to you known as uniform construction (see News, and changes, in C++/WinRT 2.0).

See XAML controls; bind to a C++/WinRT property for a full walkthrough. This section shows extracts from that walkthrough.

To use uniform construction instead of winrt::make, you'll need an activation factory. A good way to generate one is to add a constructor to your IDL.

// MainPage.idl

import "BookstoreViewModel.idl";

namespace Bookstore

{

runtimeclass MainPage : Windows.UI.Xaml.Controls.Page

{

MainPage();

BookstoreViewModel MainViewModel{ get; };

}

}

Then, in MainPage.h declare and initialize m_mainViewModel in just one step, as shown below.

// MainPage.h

...

struct MainPage : MainPageT<MainPage>

{

...

private:

Bookstore::BookstoreViewModel m_mainViewModel;

...

};

}

...

And then, in the MainPage constructor in MainPage.cpp, there's no need for the code m_mainViewModel = winrt::make<Bookstore::implementation::BookstoreViewModel>();.

For more info about uniform construction, and code examples, see Opt in to uniform construction, and direct implementation access.

Instantiating and returning projected types and interfaces

Here's an example of what projected types and interfaces might look like in your consuming project. Remember that a projected type (such as the one in this example), is tool-generated, and is not something that you'd author yourself.

struct MyRuntimeClass : MyProject::IMyRuntimeClass, impl::require<MyRuntimeClass,

Windows::Foundation::IStringable, Windows::Foundation::IClosable>

MyRuntimeClass is a projected type; projected interfaces include IMyRuntimeClass, IStringable, and IClosable. This topic has shown the different ways in which you can instantiate a projected type. Here's a reminder and summary, using MyRuntimeClass as an example.

// The runtime class is implemented in another compilation unit (it's either a Windows API,

// or it's implemented in a second- or third-party component).

MyProject::MyRuntimeClass myrc1;

// The runtime class is implemented in the same compilation unit.

MyProject::MyRuntimeClass myrc2{ nullptr };

myrc2 = winrt::make<MyProject::implementation::MyRuntimeClass>();

- You can access the members of all of the interfaces of a projected type.

- You can return a projected type to a caller.

- Projected types and interfaces derive from winrt::Windows::Foundation::IUnknown. So, you can call IUnknown::as on a projected type or interface to query for other projected interfaces, which you can also either use or return to a caller. The as member function works like QueryInterface.

void f(MyProject::MyRuntimeClass const& myrc)

{

myrc.ToString();

myrc.Close();

IClosable iclosable = myrc.as<IClosable>();

iclosable.Close();

}

Activation factories

The convenient, direct way to create a C++/WinRT object is as follows.

using namespace winrt::Windows::Globalization::NumberFormatting;

...

CurrencyFormatter currency{ L"USD" };

But there may be times that you'll want to create the activation factory yourself, and then create objects from it at your convenience. Here are some examples showing you how, using the winrt::get_activation_factory function template.

using namespace winrt::Windows::Globalization::NumberFormatting;

...

auto factory = winrt::get_activation_factory<CurrencyFormatter, ICurrencyFormatterFactory>();

CurrencyFormatter currency = factory.CreateCurrencyFormatterCode(L"USD");

using namespace winrt::Windows::Foundation;

...

auto factory = winrt::get_activation_factory<Uri, IUriRuntimeClassFactory>();

Uri uri = factory.CreateUri(L"http://www.contoso.com");

The classes in the two examples above are types from a Windows namespace. In this next example, ThermometerWRC::Thermometer is a custom type implemented in a Windows Runtime component.

auto factory = winrt::get_activation_factory<ThermometerWRC::Thermometer>();

ThermometerWRC::Thermometer thermometer = factory.ActivateInstance<ThermometerWRC::Thermometer>();

Member/Type ambiguities

When a member function has the same name as a type, there's ambiguity. The rules for C++ unqualified name lookup in member functions cause it to search the class before searching in namespaces. The substitution failure is not an error (SFINAE) rule doesn't apply (it applies during overload resolution of function templates). So if the name inside the class doesn't make sense, then the compiler doesn't keep looking for a better match—it simply reports an error.

struct MyPage : Page

{

void DoWork()

{

// This doesn't compile. You get the error

// "'winrt::Windows::Foundation::IUnknown::as':

// no matching overloaded function found".

auto style{ Application::Current().Resources().

Lookup(L"MyStyle").as<Style>() };

}

}

Above, the compiler thinks that you're passing FrameworkElement.Style() (which, in C++/WinRT, is a member function) as the template parameter to IUnknown::as. The solution is to force the name Style to be interpreted as the type Windows::UI::Xaml::Style.

struct MyPage : Page

{

void DoWork()

{

// One option is to fully-qualify it.

auto style{ Application::Current().Resources().

Lookup(L"MyStyle").as<Windows::UI::Xaml::Style>() };

// Another is to force it to be interpreted as a struct name.

auto style{ Application::Current().Resources().

Lookup(L"MyStyle").as<struct Style>() };

// If you have "using namespace Windows::UI;", then this is sufficient.

auto style{ Application::Current().Resources().

Lookup(L"MyStyle").as<Xaml::Style>() };

// Or you can force it to be resolved in the global namespace (into which

// you imported the Windows::UI::Xaml namespace when you did

// "using namespace Windows::UI::Xaml;".

auto style = Application::Current().Resources().

Lookup(L"MyStyle").as<::Style>();

}

}

Unqualified name lookup has a special exception in the case that the name is followed by ::, in which case it ignores functions, variables, and enum values. This allows you to do things like this.

struct MyPage : Page

{

void DoSomething()

{

Visibility(Visibility::Collapsed); // No ambiguity here (special exception).

}

}

The call to Visibility() resolves to the UIElement.Visibility member function name. But the parameter Visibility::Collapsed follows the word Visibility with ::, and so the method name is ignored, and the compiler finds the enum class.

Important APIs

- QueryInterface function

- RoActivateInstance function

- Windows::Foundation::Uri class

- winrt::get_activation_factory function template

- winrt::make function template

- winrt::Windows::Foundation::IUnknown struct