Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

What is a terminal?

A terminal is a concept that describes a group of input/output devices (keyboard, mouse, monitor, etc.) and configurations (settings on the devices). Consider the device you are using to read this document; are you on a desktop computer with a mouse, keyboard, and monitor? Or a mobile device with an LCD screen with touch capability and a Bluetooth keyboard? All these could be considered a terminal; they are group devices that communicate with each other.

A terminal's purpose in life is to be attached to a session.

A session is an active communication between the terminal and other devices. It is the element that holds the user's processes, data identity and runs its own win32k instance under csrss.exe (Client-server run-time subsystem). If a terminal is not attached to a session, it will be attached shortly, or it is in the process of being destroyed.

There are different types of terminals, but the two most common ones are console and remote.

Console vs. remote terminal

A console terminal is a terminal session connected to a console host, which is always active with few exceptions. There is only one active console terminal on a given machine, and all the local input/output devices are attached to that terminal.

The other common terminal is the remote terminal. A remote terminal is a terminal where all the input/output is on a remote system and not directly connected. For example, the keyboard, mouse, and monitor associated with the remote session are physically located on another system with a Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) remote terminal. This terminal is created by protocol providers (RDP, Citrix, VMware, etc.) that integrate with the Remote Desktop Services Interface. The input/output devices associated with this are considered “remote.”

Win32k and other programs can use WTS APIs like WTSQuerySessionInformation to be aware that the user is connected to the machine remotely. This is useful when devices are redirected; certain features need to be disabled, consider extra latency or take different paths.

What happens when I remote into a machine?

Below are examples of how terminals and sessions are related in a common Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) scenario.

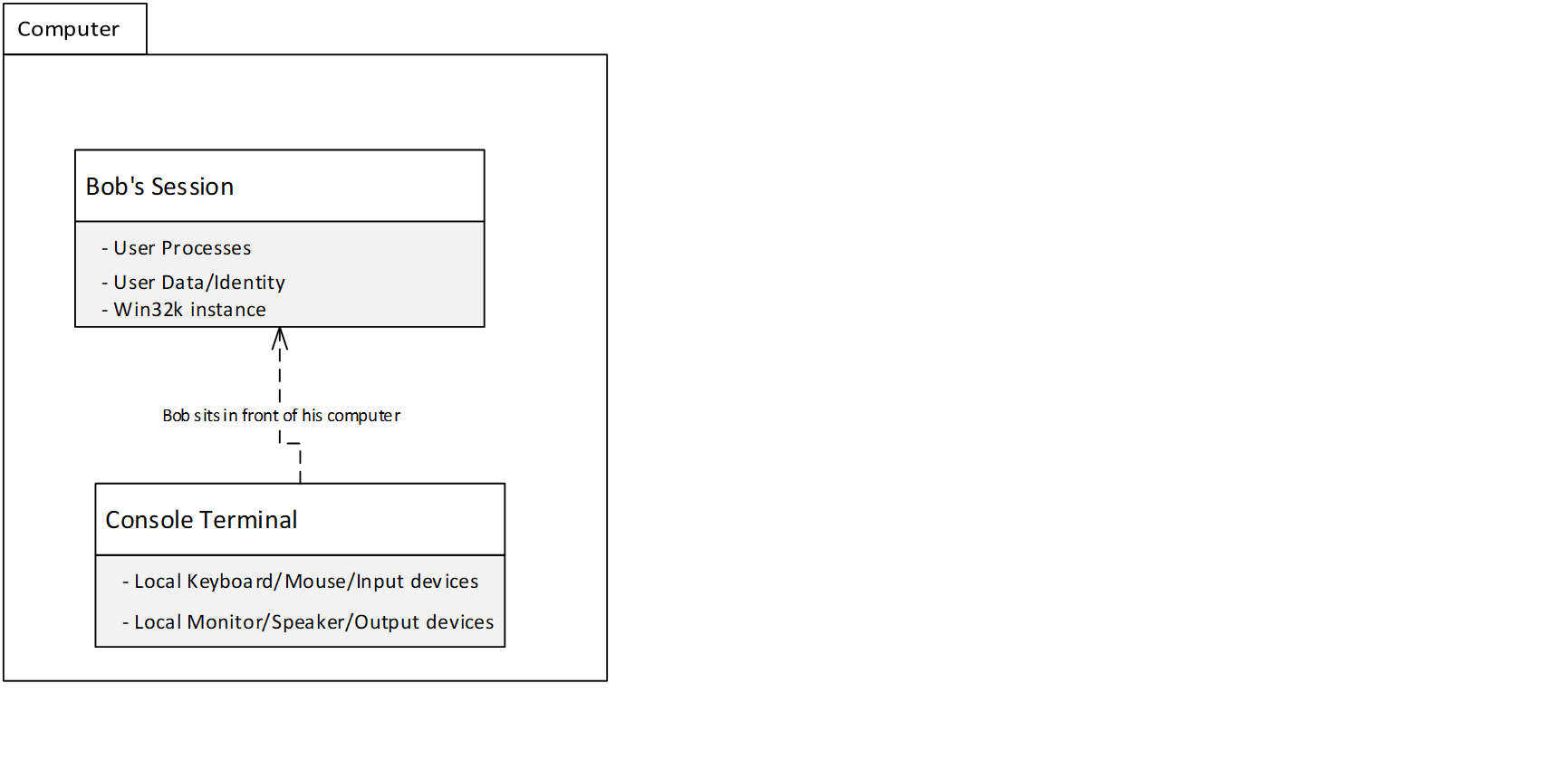

The user in front of their computer

The user, Bob, is physically at their computer and using the local devices to interact with the session. The console terminal is attached to the session.

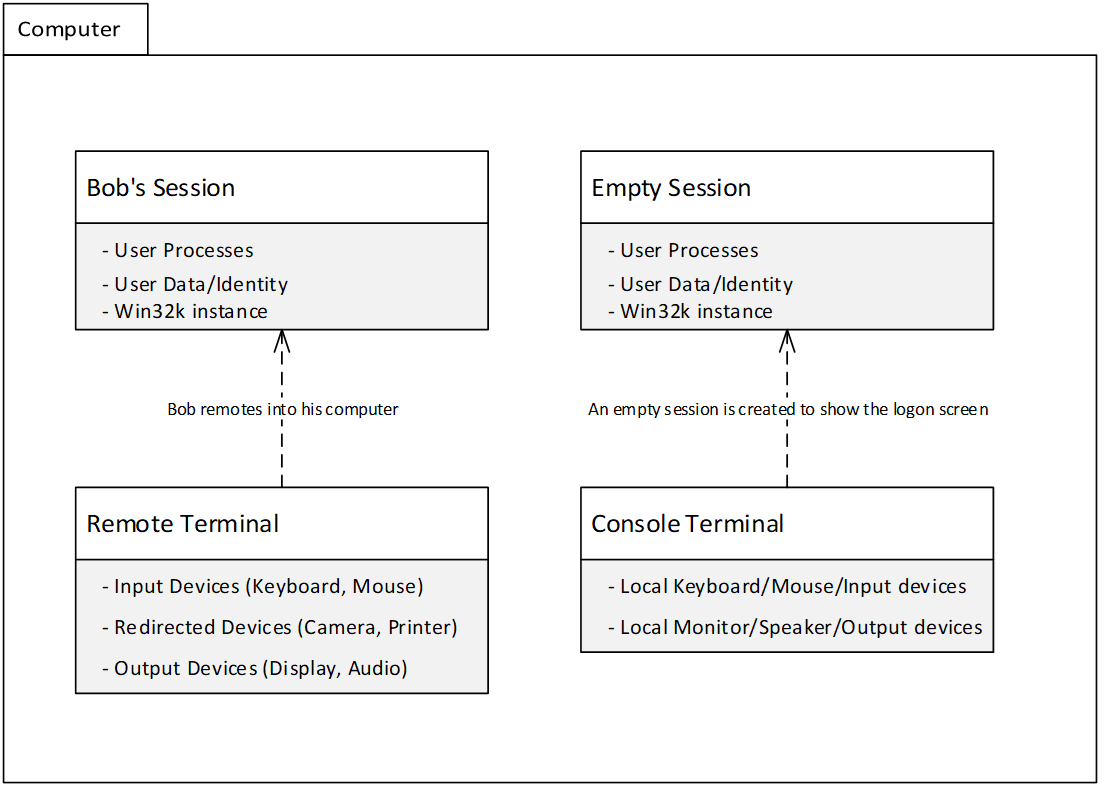

Using another machine to remote in

The user is accessing their computer from another location (not shown), so the console terminal is no longer used for their active session. Instead, it is attached to an empty session with the login screen. Unlike remote terminals, the console terminal is never terminated, and so when there is no local user at the device, it is attached to an empty session. Because the user is accessing their computer from another location, a remote terminal is instantiated and attached to the session.

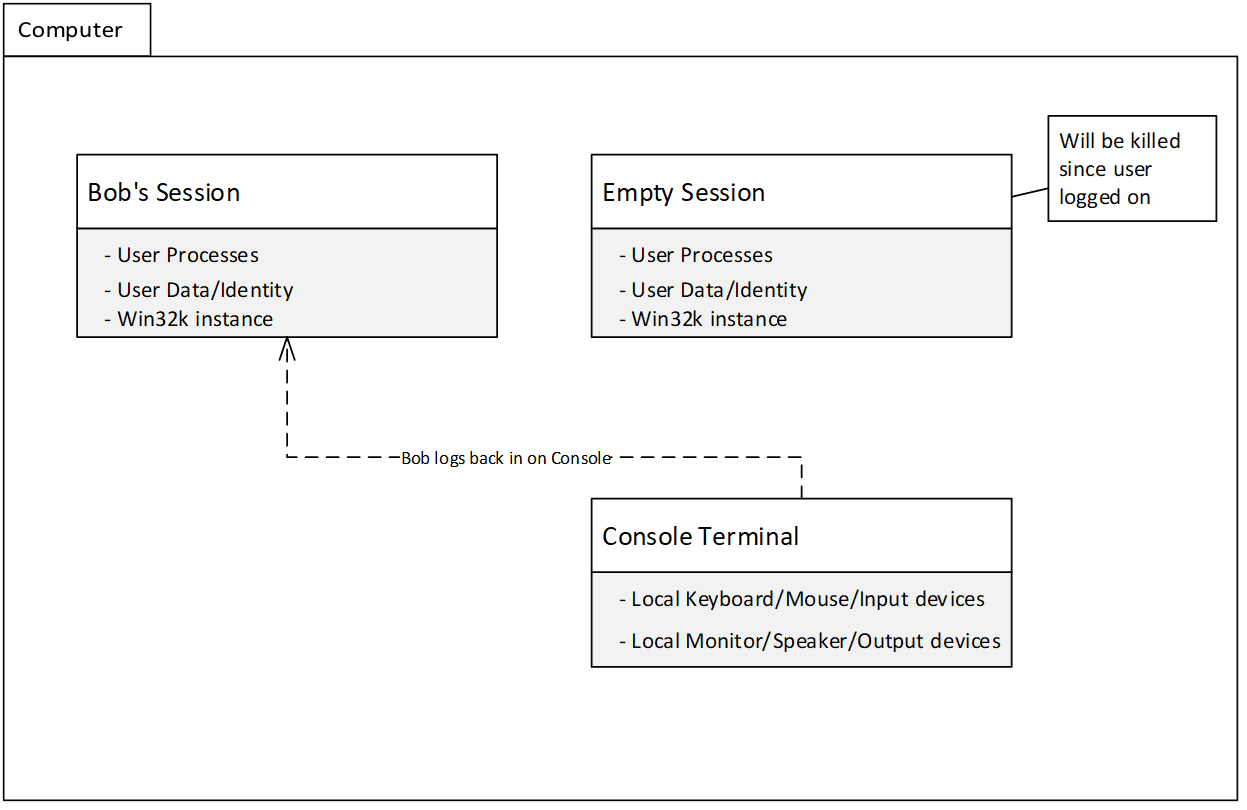

The user returns to their computer and logs back into the console terminal

When users return to their local PC, they use the local inputs and outputs to interface with the session. This means the console terminal has been reattached to the session, and the remote terminal used while remoting in is terminated.

Remote terminal lifetime

The remote terminal lifetime is similar to the lifetime of the connection from the RDP client to the RDP server. If the RDP connection gets broken due to network issues, the remote terminal gets disconnected and needs to be established.

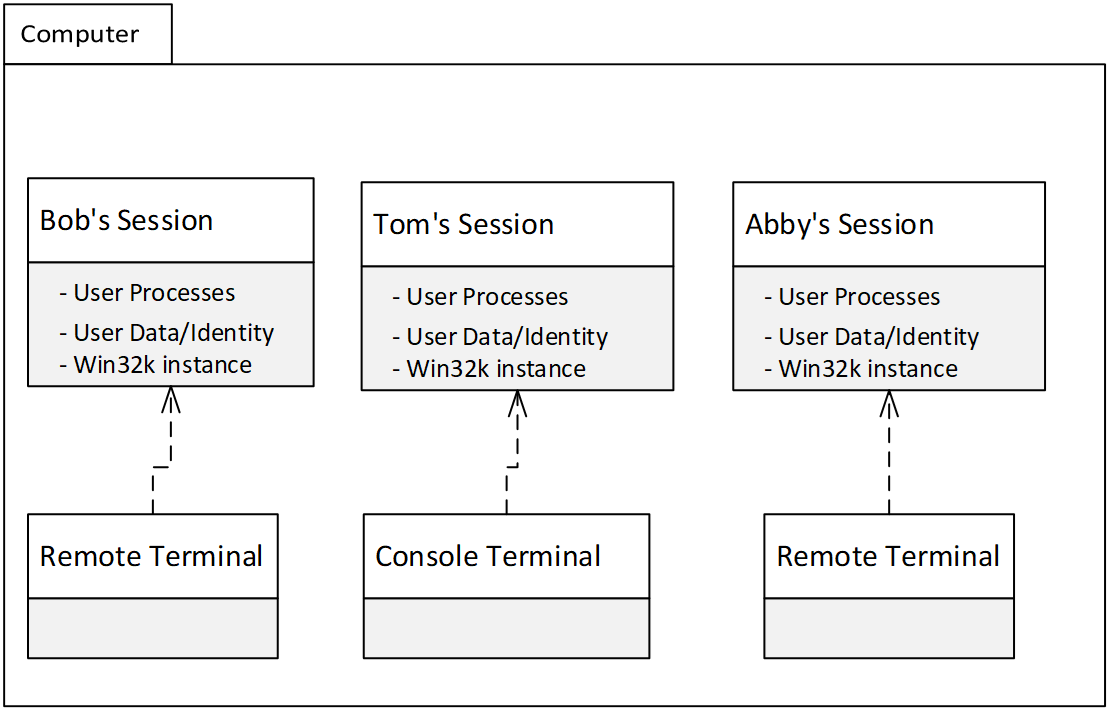

Multiple terminals and sessions

On operating systems like Windows 10 Multisession and Windows Server with the Remote Desktop Session Host (RDSH) role installed, multiple users can be logged in and have a connected terminal like the setup below. In this case, there is still only a single console terminal/session but multiple remote terminals/sessions.

In this example, Bob and Abby access the session from a remote location, instantiating a remote terminal to interface with the session. Tom accessed the session locally, which is attached to the console terminal. If Tom were too remote into the computer, their session would be attached to a remote terminal, and the console terminal would be attached to an empty session displaying the login screen.

WDDM graphics adapters and terminals

To get graphics out of a remote terminal, you need a remote Windows Display Driver Model (WDDM) indirect driver to configure your virtual monitor settings and process the desktop image to the client. There is a single instance of the WDDM remote Indirect Display driver for each remote terminal that the WDDM remote driver can expose up to 16 monitors to the remote session.

WDDM remote Indirect Display drivers can duplicate the display capabilities of the remote system. For example, if the monitor on the remote system is 1080p at 60Hz, the WDDM remote Indirect Display driver can expose a 1080p 60Hz monitor into the remote session; or if a remote client is running on an iPad, the WDDM remote Indirect Display driver for that remote terminal will expose a monitor matching the iPad display capabilities.

The display capacities of a WDDM GPU are always associated with the console terminal. This means a local monitor exposed through full WDDM driver, console WDDM Indirect Display Driver, or WDDM Display Only driver will only display the console terminal, hence the current console session. For example, a full WDDM GPU with two local monitors attached will be exposed in the console session. Still, that adapter is enumerated in a remote session without any monitors attached.

In WDDM remote sessions, the SKU's default policy (with Group policy override) decides if either WARP (CPU rasterizer) or a render GPU paired with the remote WDDM Indirect Display adapter will render the desktop and application for that remote session.