Key sovereignty, availability, performance, and scalability in Managed HSM

Cryptographic keys are the root of trust for securing modern computer systems, whether on-premises or in the cloud. So, controlling who has authority over those keys is critical to building secure and compliant applications.

In Azure, our vision of how key management should be done in the cloud is key sovereignty. Key sovereignty means that a customer's organization has full and exclusive control over who can access keys and change key management policies, and over what Azure services consume these keys. After these decisions are made by the customer, Microsoft personnel are prevented through technical means from changing these decisions. The key management service code executes the customer's decisions until the customer tells it to do otherwise, and Microsoft personnel can't intervene.

At the same time, it is our belief that every service in the cloud must be fully managed. The service must provide the required availability, resiliency, security, and cloud fundamental promises, backed by service level agreements (SLAs). To deliver a managed service, Microsoft needs to patch key management servers, upgrade hardware security module (HSM) firmware, heal failing hardware, perform failovers, and do other high-privilege operations. As most security professionals know, denying someone with high privilege or physical access to a system access to the data within that system is a difficult problem.

This article explains how we solved this problem in the Azure Key Vault Managed HSM service, giving customers both full key sovereignty and fully managed service SLAs by using confidential computing technology paired with HSMs.

Managed HSM hardware environment

A customer's Managed HSM pool in any Azure region is in a secure Azure datacenter. Three instances are spread over several servers. Each instance is deployed in a different rack to ensure redundancy. Each server has a FIPS 140-2 Level 3 validated Marvell LiquidSecurity HSM Adapter with multiple cryptographic cores. The cores are used to create fully isolated HSM partitions, including fully isolated credentials, data storage, and access control.

The physical separation of the instances inside the datacenter is critical to ensuring that the loss of a single component (for example, the top-of-rack switch or a power management unit in a rack) can't affect all the instances of a pool. These servers are dedicated to the Azure Security HSM team. The servers aren't shared with other Azure teams, and no customer workloads are deployed on these servers. Physical access controls, including locked racks, are used to prevent unauthorized access to the servers. These controls meet FedRAMP-High, PCI, SOC 1/2/3, ISO 270x, and other security and privacy standards, and are regularly independently verified as part of the Azure compliance program. The HSMs have enhanced physical security, validated to meet FIPS 140-2 Level 3 requirements. The entire Managed HSM service is built on top of the standard secure Azure platform, including trusted launch, which protects against advanced persistent threats.

The HSM adapters can support dozens of isolated HSM partitions. Running on each server is a control process called Node Service. Node Service takes ownership of each adapter and installs the credentials for the adapter owner, in this case, Microsoft. The HSM is designed so that ownership of the adapter doesn't provide Microsoft with access to data that's stored in customer partitions. It allows only Microsoft to create, resize, and delete customer partitions. It supports taking blind backups of any partition for the customer. In a blind backup, the backup is wrapped by a customer-provided key that can be restored by the service code only inside a Managed HSM instance that's owned by the customer, and whose contents aren't readable by Microsoft.

Architecture of a Managed HSM pool

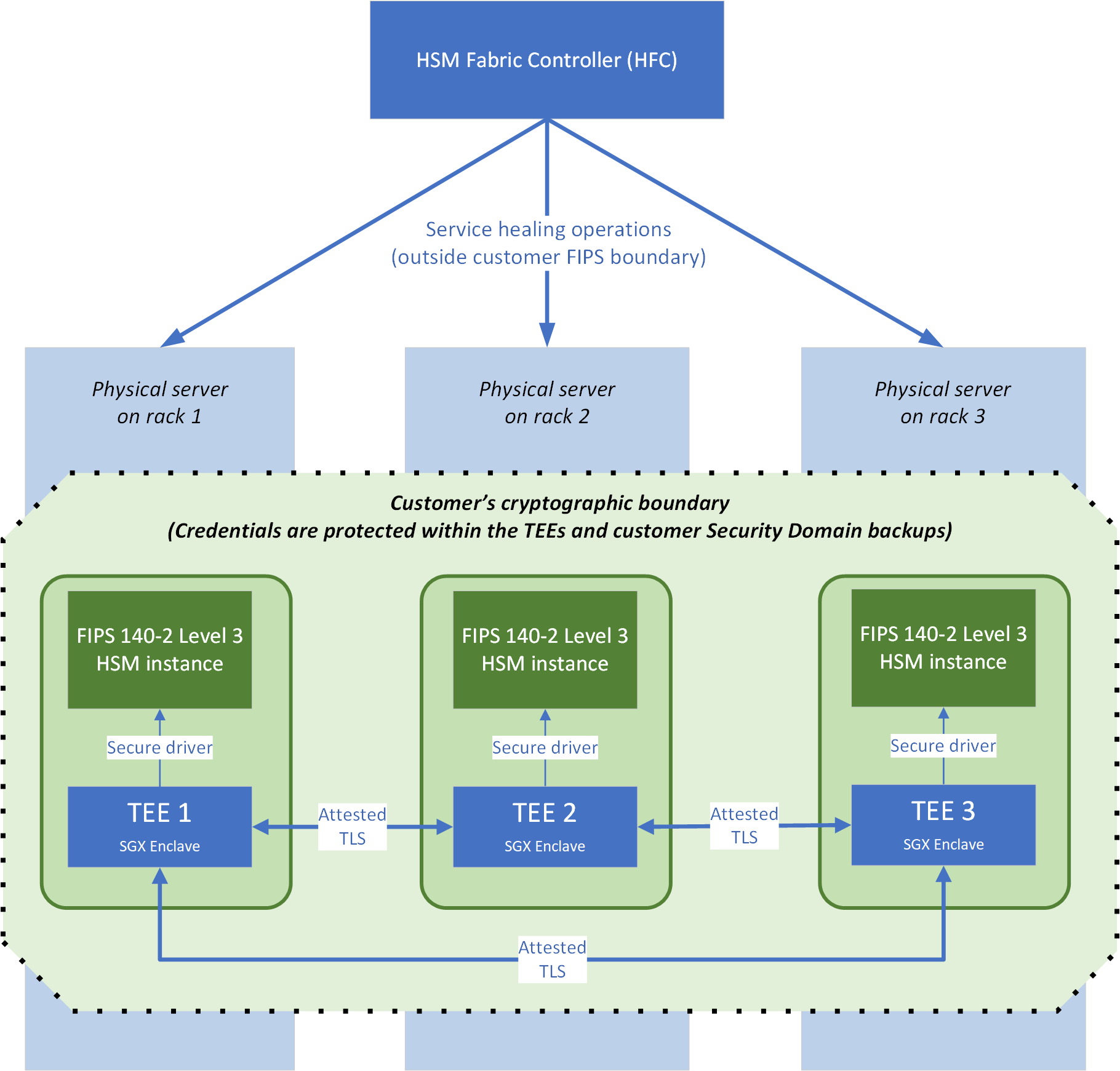

Figure 1 shows the architecture of an HSM pool, which consists of three Linux VMs, each running on an HSM server in its own datacenter rack to support availability. The important components are:

- The HSM fabric controller (HFC) is the control plane for the service. The HFC drives automated patching and repairs for the pool.

- An exclusive cryptographic boundary for each customer composed of three Intel Secure Guard Extensions (Intel SGX) confidential enclaves connected to three FIPS 140-2 Level 3 compliant HSM instances. The root keys for this boundary are generated and stored in the three HSMs. As we describe later in this article, no person associated with Microsoft has access to the data that's within this boundary. Only service code that's running in the Intel SGX enclave (including the Node Service agent), acting on behalf of the customer, has access.

Trusted execution environment (TEE)

A Managed HSM pool consists of three service instances. Each service instance is implemented as a trusted execution environment (TEE) that uses Intel SGX capabilities and the Open Enclave SDK. Execution within a TEE ensures that no person on either the virtual machine (VM) that's hosting the service or the VM's host server has access to customer secrets, data, or the HSM partition. Each TEE is dedicated to a specific customer, and it runs TLS management, request handling, and access control to the HSM partition. No credentials or customer-specific data encryption keys exist in clear text outside this TEE, except as part of the security domain package. That package is encrypted to a customer-provided key, and it downloads when their pool is first created.

The TEEs communicate among themselves by using attested TLS. Attested TLS combines the remote attestation capabilities of the Intel SGX platform with TLS 1.2. This allows Managed HSM code in the TEE to limit its communication to only other code that's signed by the same Managed HSM service code-signing key, to prevent man-in-the-middle attacks. The Managed HSM service's code-signing key is stored in Microsoft Product Release and Security Service (which is also used to store, for example, the Windows code-signing key). The key is controlled by the Managed HSM team. As part of our regulatory and compliance obligations for change management, this key can't be used by any other Microsoft team to sign its code.

The TLS certificates that are used for TEE-to-TEE communication are self-issued by the service code inside the TEE. The certificates contain a platform report that's generated by the Intel SGX enclave on the server. The platform report is signed with keys that are derived from keys fused by Intel into the CPU when it's manufactured. The report identifies the code that is loaded into the Intel SGX enclave by its code-signing key and binary hash. From this platform report, service instances can determine that a peer is also signed by the Managed HSM service code-signing key, and, with some crypto entanglement via the platform report, it can also determine that the self-issued certificate-signing key must also have been generated inside the TEE, to prevent external impersonation.

Offer availability SLAs with full customer-managed key control

To ensure high availability, the HFC service creates three HSM instances in the customer-selected Azure region.

Managed HSM pool creation

The high-availability properties of Managed HSM pools come from the automatically managed, triple-redundant HSM instances that are always kept in sync (or, if you're using multi-region replication, from keeping all six instances in sync). Pool creation is managed by the HFC service, which allocates pools across the available hardware in the Azure region that the customer chooses.

When a new pool is requested, the HFC selects three servers across several racks that have available space on their HSM adapters, and then it starts to create the pool:

The HFC instructs the Node Service agents on each of the three TEEs to launch a new instance of the service code by using a set of parameters. The parameters identify the customer's Microsoft Entra tenant, the internal virtual network IP addresses of all three instances, and some other service configurations. One partition is randomly assigned as primary.

The three instances start. Each instance connects to a partition on its local HSM adapter, and then it zeroizes and initializes the partition by using randomly generated usernames and credentials (to ensure that the partition can't be accessed by a human operator or by another TEE instance).

The primary instance creates a partition owner root certificate by using the private key that's generated in the HSM. It establishes ownership of the pool by signing a partition-level certificate for the HSM partition by using this root certificate. The primary also generates a data encryption key, which is used to protect all customer data at rest inside the service. For key material, a double wrapping is used because the HSM also protects the key material itself.

Next, this ownership data is synchronized to the two secondary instances. Each secondary contacts the primary by using attested TLS. The primary shares the partition owner root certificate with the private key and the data encryption key. The secondaries now use the partition root certificate to issue a partition certificate to their own HSM partitions. After this is done, you have HSM partitions on three separate servers that are owned by the same partition root certificate.

Over the attested TLS link, the primary's HSM partition shares with the secondaries its generated data-wrapping key (used to encrypt messages between the three HSMs) by using a secure API that's provided by the HSM vendor. During this exchange, the HSMs confirm that they have the same partition owner certificate, and then they use a Diffie-Hellman scheme to encrypt the messages so that the Microsoft service code can't read them. All that the service code can do is transport opaque blobs between the HSMs.

At this point, all three instances are ready to be exposed as a pool on the customer's virtual network. They share the same partition owner certificate and private key, the same data encryption key, and a common data-wrapping key. However, each instance has unique credentials to their HSM partitions. Now the final steps are completed.

Each instance generates an RSA key pair and a certificate signing request (CSR) for its public-facing TLS certificate. The CSR is signed by the Microsoft public key infrastructure (PKI) system by using a Microsoft public root, and the resultant TLS certificate is returned to the instance.

All three instances obtain their own Intel SGX sealing key from their local CPU. The key is generated by using the CPU's own unique key and the TEE's code-signing key.

The pool derives a unique pool key from the Intel SGX sealing keys, encrypts all its secrets by using this pool key, and then writes the encrypted blobs to disk. These blobs can be decrypted only by being code-signed by the same Intel SGX sealing key that's running on the same physical CPU. The secrets are bound to that specific instance.

The secure bootstrap process is now complete. This process has allowed for both the creation of a triple-redundant HSM pool and the creation of a cryptographic guarantee of the sovereignty of customer data.

Maintaining availability SLAs at runtime by using confidential service healing

The pool creation story that's described in this article can explain how the Managed HSM service is able to deliver its high-availability SLAs by securely managing the servers that underlie the service. Imagine that a server, an HSM adapter, or even the power supply to the rack, fails. The goal of the Managed HSM service is, without any customer intervention or the possibility of secrets being exposed in clear text outside the TEE, to heal the pool back to three healthy instances. This is achieved through confidential service healing.

It starts with the HFC detecting which pools had instances on the failed server. HFC finds new, healthy servers within the pool's region to deploy the replacement instances to. It launches new instances, which are then treated exactly as a secondary during the initial provisioning step: initialize the HSM, find its primary, securely exchange secrets over attested TLS, sign the HSM into the ownership hierarchy, and then seal its service data to its new CPU. The service is now healed, fully automatically and fully confidentially.

Recovering from disaster by using the security domain

The security domain is a secured blob that contains all the credentials that are needed to rebuild the HSM partition from scratch: the partition owner key, the partition credentials, the data-wrapping key, plus an initial backup of the HSM. Before the service becomes live, the customer must download the security domain by providing a set of RSA encryption keys to secure it. The security domain data originates in the TEEs and is protected by a generated symmetric key and an implementation of Shamir's Secret Sharing algorithm, which splits the key shares across the customer-provided RSA public keys according to customer-selected quorum parameters. During this process, none of the service keys or credentials are ever exposed in plaintext outside the service code that's running in the TEEs. Only the customer, by presenting a quorum of their RSA keys to the TEE, can decrypt the security domain during a recovery scenario.

The security domain is needed only when, due to some catastrophe, an entire Azure region is lost and Microsoft loses all three instances of the pool simultaneously. If only one instance, or even two instances, are lost, then confidential service healing will quietly recover to three healthy instances with no customer intervention. If the entire region is lost, because Intel SGX sealing keys are unique to each CPU, Microsoft has no way to recover the HSM credentials and partition owner keys. They exist only within the context of the instances.

In the extremely unlikely event that this catastrophe happens, the customer can recover their previous pool state and data by creating a new blank pool, injecting it into the security domain, and then presenting their RSA key quorum to prove ownership of the security domain. If a customer has enabled multi-region replication, the even more unlikely catastrophe of both regions experiencing a simultaneous, complete failure would have to happen before customer intervention would be needed to recover the pool from the security domain.

Controlling access to the service

As described, our service code in the TEE is the only entity that has access to the HSM itself because the necessary credentials aren't given to the customer or to anyone else. Instead, the customer's pool is bound to their Microsoft Entra instance, and this is used for authentication and authorization. At initial provisioning, the customer can choose an initial set of employees to assign the Administrator role for the pool. These individuals, and the employees in the customer's Microsoft Entra tenant Global Administrator role, can set access control policies within the pool. All access control policies are stored by the service in the same database as the masked keys, which are also encrypted. Only the service code in the TEE has access to these access control policies.

Summary

Managed HSM removes the need for customers to make tradeoffs between availability and control over cryptographic keys by using cutting-edge, hardware-backed, confidential-enclave technology. As described in this article, in this implementation, no Microsoft personnel or representative can access customer-managed key material or related secrets, even with physical access to the Managed HSM host machines and HSMs. This security has allowed our customers in financial services, manufacturing, the public sector, defense, and other verticals to accelerate their migrations to the cloud with full confidence.