Diagnose and resolve spinlock contention on SQL Server

This article provides in-depth information on how to identify and resolve issues related to spinlock contention in SQL Server applications on high-concurrency systems.

Note

The recommendations and best practices documented here are based on real-world experience during the development and deployment of real world OLTP systems. It was originally published by the Microsoft SQL Server Customer Advisory Team (SQLCAT) team.

Background

In the past, commodity Windows Server computers have utilized only one or two microprocessor/CPU chips, and CPUs have been designed with only a single processor or "core". Increases in computer processing capacity have been achieved by using faster CPUs, made possible largely through advancements in transistor density. Following "Moore's Law", transistor density or the number of transistors that can be placed on an integrated circuit have consistently doubled every two years since the development of the first general purpose single chip CPU in 1971. In recent years, the traditional approach of increasing computer processing capacity with faster CPUs has been augmented by building computers with multiple CPUs. As of this writing, the Intel Nehalem CPU architecture accommodates up to eight cores per CPU, which when used in an eight socket system can then be doubled to 128 logical processors by using simultaneous multithreading (SMT) technology. On Intel CPUs, SMT is called Hyper-Threading. As the number of logical processors on x86 compatible computers increases, concurrency-related issues increase as logical processors compete for resources. This guide describes how to identify and resolve particular resource contention issues observed when running SQL Server applications on high concurrency systems with some workloads.

In this section, we analyze the lessons learned by the SQLCAT team from diagnosing and resolving spinlock contention issues. Spinlock contention is one type of concurrency issue observed in real customer workloads on high scale systems.

Symptoms and causes of spinlock contention

This section describes how to diagnose issues with spinlock contention, which is detrimental to the performance of OLTP applications on SQL Server. Spinlock diagnosis and troubleshooting should be considered an advanced subject, which requires knowledge of debugging tools and Windows internals.

Spinlocks are lightweight synchronization primitives that are used to protect access to data structures. Spinlocks aren't unique to SQL Server. The operating system uses them when access to a given data structure is only needed for a short time. When a thread attempting to acquire a spinlock is unable to obtain access, it executes in a loop periodically checking to determine if the resource is available instead of immediately yielding. After some period of time, a thread waiting on a spinlock will yield before it's able to acquire the resource. Yielding allows other threads running on the same CPU to execute. This behavior is known as a backoff and is discussed in more depth later in this article.

SQL Server utilizes spinlocks to protect access to some of its internal data structures. Spinlocks are used within the engine to serialize access to certain data structures in a similar fashion to latches. The main difference between a latch and a spinlock is the fact that spinlocks spin (execute a loop) for a period of time checking for availability of a data structure while a thread attempting to acquire access to a structure protected by a latch immediately yields if the resource isn't available. Yielding requires context switching of a thread off the CPU so that another thread can execute. This is a relatively expensive operation and for resources that are held for a short duration it's more efficient overall to allow a thread to execute in a loop periodically checking for availability of the resource.

Internal adjustments to the Database Engine introduced in SQL Server 2022 (16.x) make spinlocks more efficient.

Symptoms

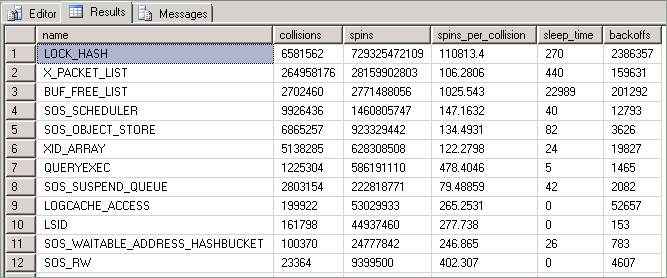

On any busy high concurrency system, it's normal to see active contention on frequently accessed structures that are protected by spinlocks. This usage is only considered problematic when contention introduces significant CPU overhead. Spinlock statistics are exposed by the sys.dm_os_spinlock_stats Dynamic Management View (DMV) within SQL Server. For example, this query yields the following output:

Note

More details about interpreting the information returned by this DMV will be discussed later in this article.

SELECT * FROM sys.dm_os_spinlock_stats

ORDER BY spins DESC;

The statistics exposed by this query are described as follows:

| Column | Description |

|---|---|

| Collisions | This value is incremented each time a thread is blocked from accessing a resource protected by a spinlock. |

| Spins | This value is incremented for each time a thread executes a loop while waiting for a spinlock to become available. This is a measure of the amount of work a thread does while it's trying to acquire a resource. |

| Spins_per_collision | Ratio of spins per collision. |

| Sleep time | Related to back-off events; not relevant to techniques described in this article however. |

| Backoffs | Occurs when a "spinning" thread that is attempting to access a held resource has determined that it needs to allow other threads on the same CPU to execute. |

For purposes of this discussion, statistics of particular interest are the number of collisions, spins, and backoff events that occur within a specific period when the system is under heavy load. When a thread attempts to access a resource protected by a spinlock, a collision occurs. When a collision occurs, the collision count is incremented and the thread will begin to spin in a loop and periodically check if the resource is available. Each time the thread spins (loops) the spin count is incremented.

Spins per collision is a measure of the amount of spins occurring while a spinlock is being held by a thread, and tells you how many spins are occurring while threads are holding the spinlock. For example, small spins per collision and high collision count means there's a small amount of spins occurring under the spinlock and there are many threads contending for it. A large amount of spins means the time spent spinning in the spinlock code relatively long lived (that is, the code is going over a large number of entries in a hash bucket). As contention increases (thus increasing collision count), the number of spins also increases.

Backoffs may be thought of in a similar fashion to spins. By design, to avoid excessive CPU waste, spinlocks don't continue spinning indefinitely until they can access a held resource. To ensure a spinlock doesn't excessively use CPU resources, spinlocks backoff, or stop spinning and "sleep". Spinlocks backoff regardless of whether they ever obtain ownership of the target resource. This is done to allow other threads to be scheduled on the CPU in the hope that this.may allow more productive work to happen. Default behavior for the engine is to spin for a constant time interval first before performing a backoff. Attempting to obtain a spinlock requires that a state of cache concurrency is maintained, which is a CPU intensive operation relative to the CPU cost of spinning. Therefore, attempts to obtain a spinlock are performed sparingly and not performed each time a thread spins. In SQL Server certain spinlock types (for example: LOCK_HASH) were improved by utilizing an exponentially increasing interval between attempts to acquire the spinlock (up to a certain limit), which often reduces the effect on CPU performance.

The following diagram provides a conceptual view of the spinlock algorithm:

Typical scenarios

Spinlock contention can occur for any number of reasons that may be unrelated to database design decisions. Because spinlocks gate access to internal data structures, spinlock contention isn't manifested in the same way as buffer latch contention, which is directly affected by schema design choices and data access patterns.

The symptom primarily associated with spinlock contention is high CPU consumption as a result of the large number of spins and many threads attempting to acquire the same spinlock. In general, this has been observed on systems with >= 24 and most commonly on >= 32 CPU core systems. As stated before, some level of contention on spinlocks is normal for high concurrency OLTP systems with significant load and there's often a large number of spins (billions/trillions) reported from the sys.dm_os_spinlock_stats DMV on systems that have been running for a long time. Again, observing a high number of spins for any given spinlock type isn't enough information to determine that there's negative impact to workload performance.

A combination of several of the following symptoms may indicate spinlock contention:

A high number of spins and backoffs are observed for a particular spinlock type.

The system is experiencing heavy CPU utilization or spikes in CPU consumption. In heavy CPU scenarios, you see high signal waits on SOS_SCHEDULER_YIELD (reported by the DMV

sys.dm_os_wait_stats).The system is experiencing high concurrency.

The CPU usage and spins are increased disproportionate to throughput.

Important

Even if each of the preceding conditions is true it's still possible that the root cause of high CPU consumption lies elsewhere. In fact, in the vast majority of the cases increased CPU will be due to reasons other than spinlock contention. Some of the more common causes for increased CPU consumption include:

Queries that become more expensive over time due to growth of the underlying data resulting in the need to perform additional logical reads of memory-resident data.

Changes in query plans resulting in suboptimal execution.

If all of these conditions are true, perform further investigation into possible spinlock contention issues.

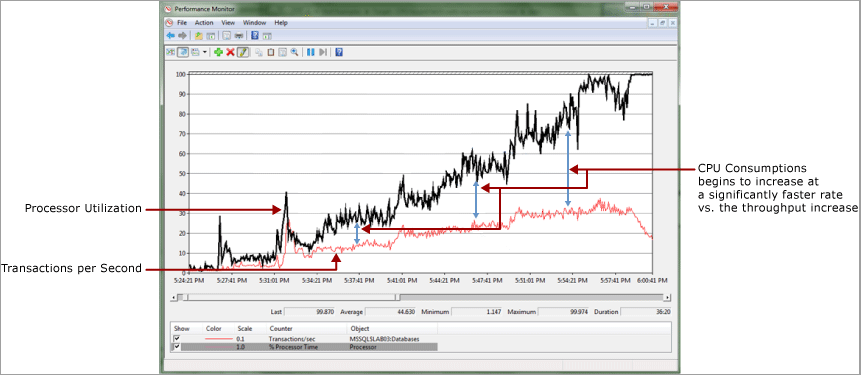

One common phenomenon easily diagnosed is a significant divergence in throughput and CPU usage. Many OLTP workloads have a relationship between (throughput / number of users on the system) and CPU consumption. High spins observed in conjunction with a significant divergence of CPU consumption and throughput can be an indication of spinlock contention introducing CPU overhead. An important thing to note here is that it's also common to see this type of divergence on systems when certain queries become more expensive over time. For example, queries that are issued against datasets that perform more logical reads over time may result in similar symptoms.

It's critical to rule out other more common causes of high CPU when troubleshooting these types of problems.

Examples

In the following example, there's a nearly linear relationship between CPU consumption and throughput as measured by transactions per second. It's normal to see some divergence here because overhead is incurred as any workload increases. As illustrated here, this divergence becomes significant. There's also a precipitous drop in throughput once CPU consumption reaches 100%.

When measuring the number of spins at 3-minute intervals we can see a more exponential than linear increase in spins, which indicates that spinlock contention may be problematic.

As stated previously spinlocks are most common on high concurrency systems that are under heavy load.

Some of the scenarios that are prone to this issue include:

Name resolution problems caused by a failure to fully qualify names of objects. For more information, see Description of SQL Server blocking caused by compile locks. This specific issue is described in more detail within this article.

Contention for lock hash buckets in the lock manager for workloads that frequently access the same lock (such as a shared lock on a frequently read row). This type of contention surfaces as a LOCK_HASH type spinlock. In one particular case, we found that this problem surfaced as a result of incorrectly modeled access patterns in a test environment. In this environment, more than the expected numbers of threads were constantly accessing the exact same row due to incorrectly configured test parameters.

High rate of DTC transactions when there's high degree of latency between the MSDTC transaction coordinators. This specific problem is documented in detail in the SQLCAT blog entry Resolving DTC Related Waits and Tuning Scalability of DTC.

Diagnose spinlock contention

This section provides information for diagnosing SQL Server spinlock contention. The primary tools used to diagnose spinlock contention are:

| Tool | Use |

|---|---|

| Performance Monitor | Look for high CPU conditions or divergence between throughput and CPU consumption. |

sys.dm_os_spinlock stats DMV** |

Look for a high number of spins and backoff events over periods of time. |

| SQL Server extended events | Used to track call stacks for spinlocks that are experiencing a high number of spins. |

| Memory dumps | In some cases, memory dumps of the SQL Server process and the Windows Debugging tools. In general, this level of analysis is done when the Microsoft SQL Server support teams are engaged. |

The general technical process for diagnosing SQL Server Spinlock contention is:

Step 1: Determine that there's contention that may be spinlock related.

Step 2: Capture statistics from

sys.dm_ os_spinlock_stats to find the spinlock type experiencing the most contention.Step 3: Obtain debug symbols for sqlservr.exe (sqlservr.pdb) and place the symbols in the same directory as the SQL Server service .exe file (sqlservr.exe) for the instance of SQL Server.\ In order to see the call stacks for the back off events, you must have symbols for the particular version of SQL Server that you're running. Symbols for SQL Server are available on the Microsoft Symbol Server. For more information about how to download symbols from the Microsoft Symbol Server, see Debugging with symbols.

Step 4: Use SQL Server Extended Events to trace the back off events for the spinlock types of interest.

Extended Events provide the ability to track the "backoff" event and capture the call stack for those operation(s) most prevalently trying to obtain the spinlock. By analyzing the call stack, it's possible to determine what type of operation is contributing to contention for any particular spinlock.

Diagnostic walkthrough

The following walkthrough shows how to use the tools and techniques to diagnose a spinlock contention problem in a real world scenario. This walkthrough is based on a customer engagement running a benchmark test to simulate approximately 6,500 concurrent users on an 8 socket, 64 physical core server with 1 TB of memory.

Symptoms

Periodic spikes in CPU were observed, which pushed the CPU utilization to nearly 100%. A divergence between throughput and CPU consumption was observed leading up to the problem. By the time that the large CPU spike occurred, a pattern of a large number of spins occurring during times of heavy CPU usage at particular intervals was established.

This was an extreme case in which the contention was such that it created a spinlock convoy condition. A convoy occurs when threads can no longer make progress servicing the workload but instead spend all processing resources attempting to gain access to the lock. The performance monitor log illustrates this divergence between transaction log throughput and CPU consumption and, ultimately, the large spike in CPU utilization.

After querying sys.dm_os_spinlock_stats to determine the existence of significant contention on SOS_CACHESTORE, an extended events script was used to measure the number of backoff events for the spinlock types of interest.

| Name | Collisions | Spins | Spins per collision | Backoffs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

SOS_CACHESTORE |

14,752,117 | 942,869,471,526 | 63,914 | 67,900,620 |

SOS_SUSPEND_QUEUE |

69,267,367 | 473,760,338,765 | 6,840 | 2,167,281 |

LOCK_HASH |

5,765,761 | 260,885,816,584 | 45,247 | 3,739,208 |

MUTEX |

2,802,773 | 9,767,503,682 | 3,485 | 350,997 |

SOS_SCHEDULER |

1,207,007 | 3,692,845,572 | 3,060 | 109,746 |

The most straightforward way to quantify the impact of the spins is to look at the number of backoff events exposed by sys.dm_os_spinlock_stats over the same 1-minute interval for the spinlock type(s) with the highest number of spins. This method is best to detect significant contention because it indicates when threads are exhausting the spin limit while waiting to acquire the spinlock. The following script illustrates an advanced technique that utilizes extended events to measure related backoff events and identify the specific code paths where the contention lies.

For more information about Extended Events in SQL Server, see Introducing SQL Server Extended Events.

Script

/*

This script is provided "AS IS" with no warranties, and confers no rights.

This script will monitor for backoff events over a given period of time and

capture the code paths (callstacks) for those.

--Find the spinlock types

select map_value, map_key, name from sys.dm_xe_map_values

where name = 'spinlock_types'

order by map_value asc

--Example: Get the type value for any given spinlock type

select map_value, map_key, name from sys.dm_xe_map_values

where map_value IN ('SOS_CACHESTORE', 'LOCK_HASH', 'MUTEX')

Examples:

61LOCK_HASH

144 SOS_CACHESTORE

08MUTEX

*/

--create the even session that will capture the callstacks to a bucketizer

--more information is available in this reference: http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/bb630354.aspx

CREATE EVENT SESSION spin_lock_backoff ON SERVER

ADD EVENT sqlos.spinlock_backoff (

ACTION(package0.callstack) WHERE type = 61 --LOCK_HASH

OR TYPE = 144 --SOS_CACHESTORE

OR TYPE = 8 --MUTEX

) ADD TARGET package0.asynchronous_bucketizer (

SET filtering_event_name = 'sqlos.spinlock_backoff',

source_type = 1,

source = 'package0.callstack'

)

WITH (

MAX_MEMORY = 50 MB,

MEMORY_PARTITION_MODE = PER_NODE

);

--Ensure the session was created

SELECT * FROM sys.dm_xe_sessions

WHERE name = 'spin_lock_backoff';

--Run this section to measure the contention

ALTER EVENT SESSION spin_lock_backoff ON SERVER STATE = START;

--wait to measure the number of backoffs over a 1 minute period

WAITFOR DELAY '00:01:00';

--To view the data

--1. Ensure the sqlservr.pdb is in the same directory as the sqlservr.exe

--2. Enable this trace flag to turn on symbol resolution

DBCC TRACEON (3656, -1);

--Get the callstacks from the bucketize target

SELECT event_session_address,

target_name,

execution_count,

cast(target_data AS XML)

FROM sys.dm_xe_session_targets xst

INNER JOIN sys.dm_xe_sessions xs

ON (xst.event_session_address = xs.address)

WHERE xs.name = 'spin_lock_backoff';

--clean up the session

ALTER EVENT SESSION spin_lock_backoff ON SERVER STATE = STOP;

DROP EVENT SESSION spin_lock_backoff ON SERVER;

By analyzing the output, we can see the call stacks for the most common code paths for the SOS_CACHESTORE spins. The script was run a couple of different times during the time when CPU utilization was high to check for consistency in the call stacks returned. The call stacks with the highest slot bucket count are common between the two outputs (35,668 and 8,506). These call stacks have a "slot count" that is two orders of magnitude greater than the next highest entry. This condition indicates a code path of interest.

Note

It isn't uncommon to see call stacks returned by the previous script. When the script ran for 1 minute, we observed that call stacks with a slot count of > 1000 was problematic but the slot count of > 10,000 was more likely to be problematic since it's a higher slot count.

Note

The formatting of the following output has been cleaned for readability purposes.

Output 1

<BucketizerTarget truncated="0" buckets="256">

<Slot count="35668" trunc="0">

<value>

XeSosPkg::spinlock_backoff::Publish

SpinlockBase::Sleep

SpinlockBase::Backoff

Spinlock<144,1,0>::SpinToAcquireOptimistic

SOS_CacheStore::GetUserData

OpenSystemTableRowset

CMEDScanBase::Rowset

CMEDScan::StartSearch

CMEDCatalogOwner::GetOwnerAliasIdFromSid

CMEDCatalogOwner::LookupPrimaryIdInCatalog CMEDCacheEntryFactory::GetProxiedCacheEntryByAltKey

CMEDCatalogOwner::GetProxyOwnerBySID

CMEDProxyDatabase::GetOwnerBySID

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

NTGroupInfo::`vector deleting destructor'

</value>

</Slot>

<Slot count="752" trunc="0">

<value>

XeSosPkg::spinlock_backoff::Publish

SpinlockBase::Sleep

SpinlockBase::Backoff

Spinlock<144,1,0>::SpinToAcquireOptimistic

SOS_CacheStore::GetUserData

OpenSystemTableRowset

CMEDScanBase::Rowset

CMEDScan::StartSearch

CMEDCatalogOwner::GetOwnerAliasIdFromSid CMEDCatalogOwner::LookupPrimaryIdInCatalog CMEDCacheEntryFactory::GetProxiedCacheEntryByAltKey CMEDCatalogOwner::GetProxyOwnerBySID

CMEDProxyDatabase::GetOwnerBySID

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

</value>

</Slot>

Output 2

<BucketizerTarget truncated="0" buckets="256">

<Slot count="8506" trunc="0">

<value>

XeSosPkg::spinlock_backoff::Publish

SpinlockBase::Sleep+c7 [ @ 0+0x0 SpinlockBase::Backoff Spinlock<144,1,0>::SpinToAcquireOptimistic

SOS_CacheStore::GetUserData

OpenSystemTableRowset

CMEDScanBase::Rowset

CMEDScan::StartSearch

CMEDCatalogOwner::GetOwnerAliasIdFromSid CMEDCatalogOwner::LookupPrimaryIdInCatalog CMEDCacheEntryFactory::GetProxiedCacheEntryByAltKey CMEDCatalogOwner::GetProxyOwnerBySID

CMEDProxyDatabase::GetOwnerBySID

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

NTGroupInfo::`vector deleting destructor'

</value>

</Slot>

<Slot count="190" trunc="0">

<value>

XeSosPkg::spinlock_backoff::Publish

SpinlockBase::Sleep

SpinlockBase::Backoff

Spinlock<144,1,0>::SpinToAcquireOptimistic

SOS_CacheStore::GetUserData

OpenSystemTableRowset

CMEDScanBase::Rowset

CMEDScan::StartSearch

CMEDCatalogOwner::GetOwnerAliasIdFromSid CMEDCatalogOwner::LookupPrimaryIdInCatalog CMEDCacheEntryFactory::GetProxiedCacheEntryByAltKey CMEDCatalogOwner::GetProxyOwnerBySID

CMEDProxyDatabase::GetOwnerBySID

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

ISECTmpEntryStore::Get

</value>

</Slot>

In the previous example, the most interesting stacks have the highest Slot Counts (35,668 and 8,506), which, in fact, have a slot count > 1000.

Now the question may be, "what do I do with this information"? In general, deep knowledge of the SQL Server engine is required to make use of the callstack information and so at this point the troubleshooting process moves into a gray area. In this particular case, by looking at the call stacks, we can see that the code path where the issue occurs is related to security and metadata lookups (As evident by the following stack frames CMEDCatalogOwner::GetProxyOwnerBySID & CMEDProxyDatabase::GetOwnerBySID).

In isolation, it's difficult to use this information to resolve the problem but it does give us some ideas where to focus additional troubleshooting to isolate the issue further.

Because this issue looked to be related to code paths that perform security-related checks, we decided to run a test in which the application user connecting to the database was granted sysadmin privileges. While this technique is never recommended in a production environment, in our test environment it proved to be a useful troubleshooting step. When the sessions were run using elevated privileges (sysadmin), the CPU spikes related to contention disappeared.

Options and workarounds

Clearly, troubleshooting spinlock contention can be a non-trivial task. There's no "one common best approach". The first step in troubleshooting and resolving any performance problem is to identify root cause. Using the techniques and tools described in this article is the first step in performing the analysis needed to understand the spinlock-related contention points.

As new versions of SQL Server are developed, the engine continues to improve scalability by implementing code that is better optimized for high concurrency systems. SQL Server has introduced many optimizations for high concurrency systems, one of which being exponential backoff for the most common contention points. There are specific enhancements starting in SQL Server 2012 that specifically improve this particular area by leveraging exponential backoff algorithms for all spinlocks within the engine.

When designing high end applications that need extreme performance and scale, consider how to keep the code path needed within SQL Server as short as possible. A shorter code path means less work is performed by the database engine and will naturally avoid contention points. Many best practices have a side effect of reducing the amount of work required of the engine, and hence, result optimizing workload performance.

Taking a couple best practices from earlier in this article as examples:

Fully Qualified Names: Fully qualifying names of all objects will result in removing the need for SQL Server to execute code paths that are required to resolve names. We have observed contention points also on the SOS_CACHESTORE spinlock type encountered when not utilizing fully qualified names in calls to stored procedures. Failure to fully qualify these names results in the need for SQL Server to look up the default schema for the user, which results in a longer code path required to execute the SQL.

Parameterized Queries: Another example is utilizing parameterized queries and stored procedure calls to reduce the work needed to generate execution plans. This again results in a shorter code path for execution.

LOCK_HASH Contention: Contention on certain lock structure or hash bucket collisions is unavoidable in some cases. Even though the SQL Server engine partitions the majority of lock structures, there are still times when acquiring a lock results in access the same hash bucket. For example, an application the accesses the same row by many threads concurrently (that is, reference data). These types of problems can be approached by techniques that either scale out this reference data within the database schema or use NOLOCK hints when possible.

The first line of defensive in tuning SQL Server workloads is always the standard tuning practices (for example, indexing, query optimization, I/O optimization, etc.). However, in addition to the standard tuning one would perform, following practices that reduce the amount of code needed to perform operations is an important approach. Even when best practices are followed, there's still a chance that spinlock contention may occur on busy high concurrency systems. Use of the tools and techniques in this article can help to isolate or rule out these types of problems and determine when it's necessary to engage the right Microsoft resources to help.

Hopefully these techniques will provide both a useful methodology for this type of troubleshooting and insight into some of the more advanced performance profiling techniques available with SQL Server.

Appendix: Automate memory dump capture

The following extended events script has proven to be useful to automate the collection of memory dumps when spinlock contention becomes significant. In some cases, memory dumps will be required to perform a complete diagnosis of the problem or will be requested by Microsoft support teams to perform in-depth analysis. In SQL Server 2008, there's a limit of 16 frames in callstacks captured by the bucketizer, which may not be deep enough to determine exactly where in the engine the callstack is being entered from. SQL Server 2012 introduced improvements by increasing the number of frames in callstacks captured by the bucketizer to 32.

The following SQL script can be used to automate the process of capturing memory dumps to help analyze spinlock contention:

/*

This script is provided "AS IS" with no warranties, and confers no rights.

Use: This procedure will monitor for spinlocks with a high number of backoff events

over a defined time period which would indicate that there is likely significant

spin lock contention.

Modify the variables noted below before running.

Requires:

xp_cmdshell to be enabled

sp_configure 'xp_cmd', 1

go

reconfigure

go

*********************************************************************************************************/

USE tempdb;

GO

IF object_id('sp_xevent_dump_on_backoffs') IS NOT NULL

DROP PROCEDURE sp_xevent_dump_on_backoffs

GO

CREATE PROCEDURE sp_xevent_dump_on_backoffs (

@sqldumper_path NVARCHAR(max) = '"c:\Program Files\Microsoft SQL Server\100\Shared\SqlDumper.exe"',

@dump_threshold INT = 500, --capture mini dump when the slot count for the top bucket exceeds this

@total_delay_time_seconds INT = 60, --poll for 60 seconds

@PID INT = 0,

@output_path NVARCHAR(MAX) = 'c:\',

@dump_captured_flag INT = 0 OUTPUT

)

AS

/*

--Find the spinlock types

select map_value, map_key, name from sys.dm_xe_map_values

where name = 'spinlock_types'

order by map_value asc

--Example: Get the type value for any given spinlock type

select map_value, map_key, name from sys.dm_xe_map_values

where map_value IN ('SOS_CACHESTORE', 'LOCK_HASH', 'MUTEX')

*/

IF EXISTS (

SELECT *

FROM sys.dm_xe_session_targets xst

INNER JOIN sys.dm_xe_sessions xs

ON (xst.event_session_address = xs.address)

WHERE xs.name = 'spinlock_backoff_with_dump'

)

DROP EVENT SESSION spinlock_backoff_with_dump

ON SERVER

CREATE EVENT SESSION spinlock_backoff_with_dump ON SERVER

ADD EVENT sqlos.spinlock_backoff (

ACTION(package0.callstack) WHERE type = 61 --LOCK_HASH

--or type = 144 --SOS_CACHESTORE

--or type = 8 --MUTEX

--or type = 53 --LOGCACHE_ACCESS

--or type = 41 --LOGFLUSHQ

--or type = 25 --SQL_MGR

--or type = 39 --XDESMGR

) ADD target package0.asynchronous_bucketizer (

SET filtering_event_name = 'sqlos.spinlock_backoff',

source_type = 1,

source = 'package0.callstack'

)

WITH (

MAX_MEMORY = 50 MB,

MEMORY_PARTITION_MODE = PER_NODE

)

ALTER EVENT SESSION spinlock_backoff_with_dump ON SERVER STATE = START;

DECLARE @instance_name NVARCHAR(MAX) = @@SERVICENAME;

DECLARE @loop_count INT = 1;

DECLARE @xml_result XML;

DECLARE @slot_count BIGINT;

DECLARE @xp_cmdshell NVARCHAR(MAX) = NULL;

--start polling for the backoffs

PRINT 'Polling for: ' + convert(VARCHAR(32), @total_delay_time_seconds) + ' seconds';

WHILE (@loop_count < CAST(@total_delay_time_seconds / 1 AS INT))

BEGIN

WAITFOR DELAY '00:00:01'

--get the xml from the bucketizer for the session

SELECT @xml_result = CAST(target_data AS XML)

FROM sys.dm_xe_session_targets xst

INNER JOIN sys.dm_xe_sessions xs

ON (xst.event_session_address = xs.address)

WHERE xs.name = 'spinlock_backoff_with_dump';

--get the highest slot count from the bucketizer

SELECT @slot_count = @xml_result.value(N'(//Slot/@count)[1]', 'int');

--if the slot count is higher than the threshold in the one minute period

--dump the process and clean up session

IF (@slot_count > @dump_threshold)

BEGIN

PRINT 'exec xp_cmdshell ''' + @sqldumper_path + ' ' + convert(NVARCHAR(max), @PID) + ' 0 0x800 0 c:\ '''

SELECT @xp_cmdshell = 'exec xp_cmdshell ''' + @sqldumper_path + ' ' + convert(NVARCHAR(max), @PID) + ' 0 0x800 0 ' + @output_path + ' '''

EXEC sp_executesql @xp_cmdshell

PRINT 'loop count: ' + convert(VARCHAR(128), @loop_count)

PRINT 'slot count: ' + convert(VARCHAR(128), @slot_count)

SET @dump_captured_flag = 1

BREAK

END

--otherwise loop

SET @loop_count = @loop_count + 1

END;

--see what was collected then clean up

DBCC TRACEON (3656, -1);

SELECT event_session_address,

target_name,

execution_count,

cast(target_data AS XML)

FROM sys.dm_xe_session_targets xst

INNER JOIN sys.dm_xe_sessions xs

ON (xst.event_session_address = xs.address)

WHERE xs.name = 'spinlock_backoff_with_dump';

ALTER EVENT SESSION spinlock_backoff_with_dump ON SERVER STATE = STOP;

DROP EVENT SESSION spinlock_backoff_with_dump ON SERVER;

GO

/* CAPTURE THE DUMPS

******************************************************************/

--Example: This will run continuously until a dump is created.

DECLARE @sqldumper_path NVARCHAR(MAX) = '"c:\Program Files\Microsoft SQL Server\100\Shared\SqlDumper.exe"';

DECLARE @dump_threshold INT = 300; --capture mini dump when the slot count for the top bucket exceeds this

DECLARE @total_delay_time_seconds INT = 60; --poll for 60 seconds

DECLARE @PID INT = 0;

DECLARE @flag TINYINT = 0;

DECLARE @dump_count TINYINT = 0;

DECLARE @max_dumps TINYINT = 3; --stop after collecting this many dumps

DECLARE @output_path NVARCHAR(max) = 'c:\'; --no spaces in the path please :)

--Get the process id for sql server

DECLARE @error_log TABLE (

LogDate DATETIME,

ProcessInfo VARCHAR(255),

TEXT VARCHAR(max)

);

INSERT INTO @error_log

EXEC ('xp_readerrorlog 0, 1, ''Server Process ID''');

SELECT @PID = convert(INT, (REPLACE(REPLACE(TEXT, 'Server Process ID is ', ''), '.', '')))

FROM @error_log

WHERE TEXT LIKE ('Server Process ID is%');

PRINT 'SQL Server PID: ' + convert(VARCHAR(6), @PID);

--Loop to monitor the spinlocks and capture dumps. while (@dump_count < @max_dumps)

BEGIN

EXEC sp_xevent_dump_on_backoffs @sqldumper_path = @sqldumper_path,

@dump_threshold = @dump_threshold,

@total_delay_time_seconds = @total_delay_time_seconds,

@PID = @PID,

@output_path = @output_path,

@dump_captured_flag = @flag OUTPUT

IF (@flag > 0)

SET @dump_count = @dump_count + 1

PRINT 'Dump Count: ' + convert(VARCHAR(2), @dump_count)

WAITFOR DELAY '00:00:02'

END;

Appendix: Capture spinlock statistics over time

The following script can be used to look at spinlock statistics over a specific time period. Each time it runs it will return the delta between the current values and previous values collected.

/* Snapshot the current spinlock stats and store so that this can be compared over a time period

Return the statistics between this point in time and the last collection point in time.

**This data is maintained in tempdb so the connection must persist between each execution**

**alternatively this could be modified to use a persisted table in tempdb. if that

is changed code should be included to clean up the table at some point.**

*/

USE tempdb;

GO

DECLARE @current_snap_time DATETIME;

DECLARE @previous_snap_time DATETIME;

SET @current_snap_time = GETDATE();

IF NOT EXISTS (

SELECT name

FROM tempdb.sys.sysobjects

WHERE name LIKE '#_spin_waits%'

)

CREATE TABLE #_spin_waits (

lock_name VARCHAR(128),

collisions BIGINT,

spins BIGINT,

sleep_time BIGINT,

backoffs BIGINT,

snap_time DATETIME

);

--capture the current stats

INSERT INTO #_spin_waits (

lock_name,

collisions,

spins,

sleep_time,

backoffs,

snap_time

)

SELECT name,

collisions,

spins,

sleep_time,

backoffs,

@current_snap_time

FROM sys.dm_os_spinlock_stats;

SELECT TOP 1 @previous_snap_time = snap_time

FROM #_spin_waits

WHERE snap_time < (

SELECT max(snap_time)

FROM #_spin_waits

)

ORDER BY snap_time DESC;

--get delta in the spin locks stats

SELECT TOP 10 spins_current.lock_name,

(spins_current.collisions - spins_previous.collisions) AS collisions,

(spins_current.spins - spins_previous.spins) AS spins,

(spins_current.sleep_time - spins_previous.sleep_time) AS sleep_time,

(spins_current.backoffs - spins_previous.backoffs) AS backoffs,

spins_previous.snap_time AS [start_time],

spins_current.snap_time AS [end_time],

DATEDIFF(ss, @previous_snap_time, @current_snap_time) AS [seconds_in_sample]

FROM #_spin_waits spins_current

INNER JOIN (

SELECT *

FROM #_spin_waits

WHERE snap_time = @previous_snap_time

) spins_previous

ON (spins_previous.lock_name = spins_current.lock_name)

WHERE spins_current.snap_time = @current_snap_time

AND spins_previous.snap_time = @previous_snap_time

AND spins_current.spins > 0

ORDER BY (spins_current.spins - spins_previous.spins) DESC;

--clean up table

DELETE

FROM #_spin_waits

WHERE snap_time = @previous_snap_time;