Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

Important

Visual Studio for Mac was retired on August 31, 2024 in accordance with Microsoft’s Modern Lifecycle Policy. While you can continue to work with Visual Studio for Mac, there are several other options for developers on Mac such as the preview version of the new C# Dev Kit extension for VS Code.

Unity is a game engine that enables you to develop games in C#. This walkthrough shows how to get started developing and debugging Unity games using Visual Studio for Mac and the Visual Studio for Mac Tools for Unity extension alongside the Unity environment.

Visual Studio for Mac Tools for Unity is a free extension, installed with Visual Studio for Mac. It enables Unity developers to take advantage of the productivity features of Visual Studio for Mac, including excellent IntelliSense support, debugging features, and more.

Objectives

- Learn about Unity development with Visual Studio for Mac

Prerequisites

- Visual Studio for Mac (https://www.visualstudio.com/vs/mac)

- Unity 5.6.1 Personal Edition or higher (https://store.unity.com, requires a unity.com account to run)

Intended audience

This lab is intended for developers who are familiar with C#, although deep experience isn't required.

Task 1: Creating a basic Unity project

Launch Unity. Sign in if requested.

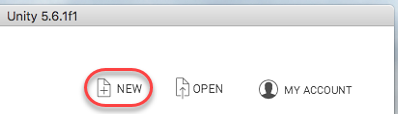

Select New.

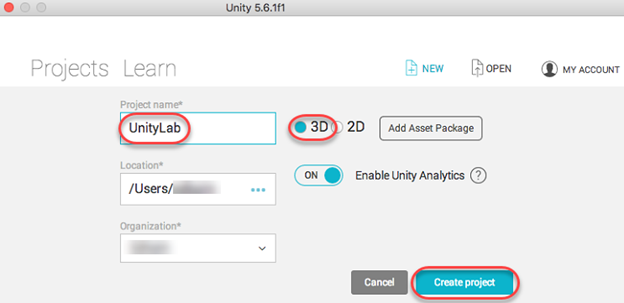

Set the Project name to "UnityLab" and select 3D. Select Create project.

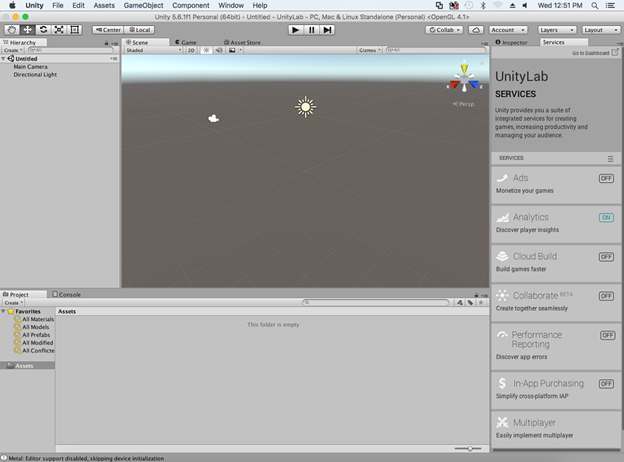

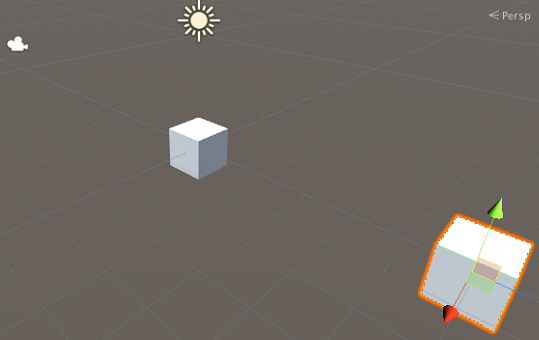

You're now looking at the default Unity interface. It has the scene hierarchy with game objects on the left, a 3D view of the blank scene shown in the middle, a project files pane on the bottom, and Inspector and Services on the right. There's a lot more to it than that, but those are few of the more important components.

For developers new to Unity, everything that runs in your app will exist within the context of a scene. A scene file is a single file that contains all sorts of metadata about the resources used in the project for the current scene and its properties. When you package your app for a platform, the resulting app will end up being a collection of one or more scenes, plus any platform-dependent code you add. You can have as many scenes as desired in a project.

The new scene just has a camera and a directional light in it. A scene requires a camera for anything to be visible and an Audio Listener for anything to be audible. These components are attached to a GameObject.

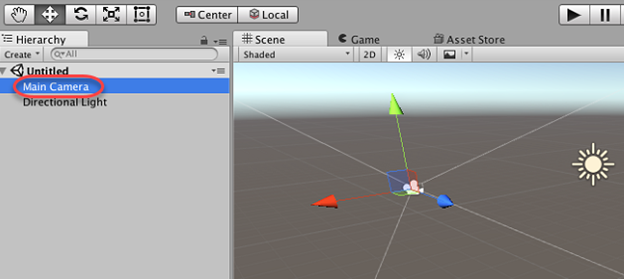

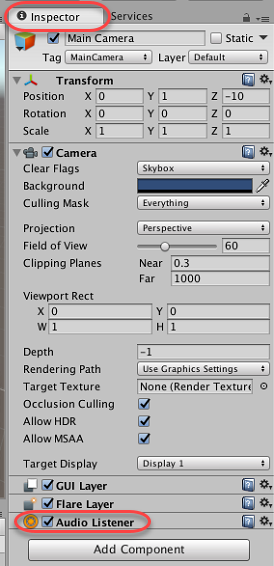

Select the Main Camera object from the Hierarchy pane.

Select the Inspector pane from the right side of the window to review its properties. Camera properties include transform information, background, projection type, field of view, and so on. An Audio Listener component was also added by default, which essentially renders scene audio from a virtual microphone attached to the camera.

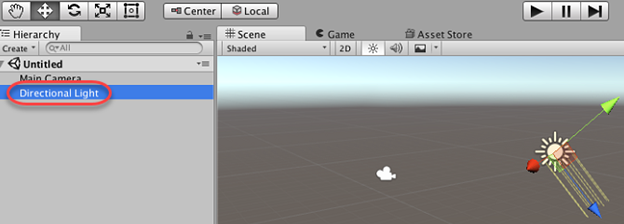

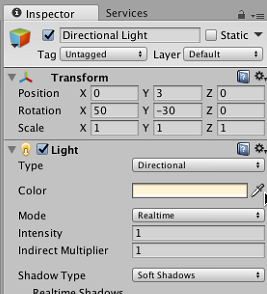

Select the Directional Light object. This provides light to the scene so that components like shaders know how to render objects.

Use the Inspector to see that it includes common lighting properties including type, color, intensity, shadow type, and so on.

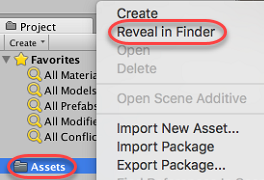

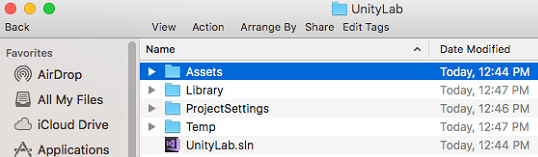

It's important to point out that projects in Unity are a little different from their Visual Studio for Mac counterparts. In the Project tab on the bottom, right-click the Assets folder and select Reveal in Finder.

Projects contain Assets, Library, ProjectSettings, and Temp folders as you can see. However, the only one that shows up in the interface is the Assets folder. The Library folder is the local cache for imported assets; it holds all metadata for assets. The ProjectSettings folder stores settings you can configure. The Temp folder is used for temporary files from Mono and Unity during the build process. There's also a solution file that you can open in Visual Studio for Mac (UnityLab.sln here).

Close the Finder window and return to Unity.

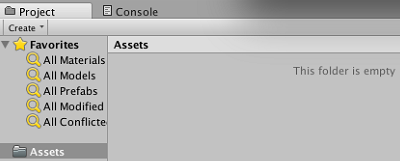

The Assets folder contains all your assets-art, code, audio, etc. It's empty now, but every single file you bring into your project goes here. This is always the top-level folder in the Unity Editor. But always add and remove files via the Unity interface (or Visual Studio for Mac) and never through the file system directly.

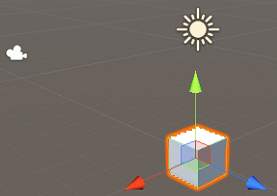

The GameObject is central to development in Unity as almost everything derives from that type, including models, lights, particle systems, and so on. Add a new Cube object to the scene via the GameObject > 3D Object > Cube menu.

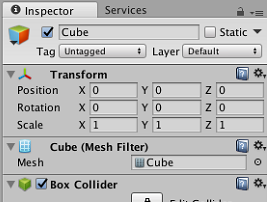

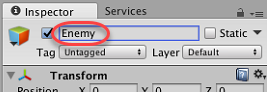

Take a quick look at the properties of the new GameObject and see that it has a name, tag, layer, and transform. These properties are common to all GameObjects. In addition, several components were attached to the Cube to provide needed functionality including mesh filter, box collider, and renderer.

Rename the Cube object, which has the name "Cube" by default, to "Enemy". Make sure to press Enter to save the change. This will be the enemy cube in our simple game.

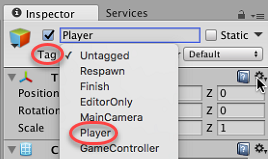

Add another Cube object to the scene using the same process as above, and name this one "Player".

Tag the player object "Player" as well (see Tag drop-down control just under name field). We'll use this in the enemy script to help locate the player game object.

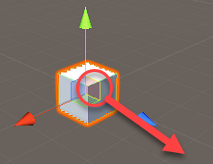

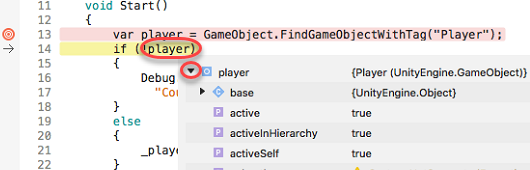

In the Scene view, move the player object away from the enemy object along the Z axis using the mouse. You can move along the Z axis by selecting and dragging the cube by its red panel toward the blue line. Since the cube lives in 3D space, but can only be dragged in 2D each time, the axis on which you drag is especially important.

Move the cube downward and to the right along the axis. This updates the Transform.Position property in the Inspector. Be sure to drag to a location similarly to what's shown here to make later steps easier in the lab.

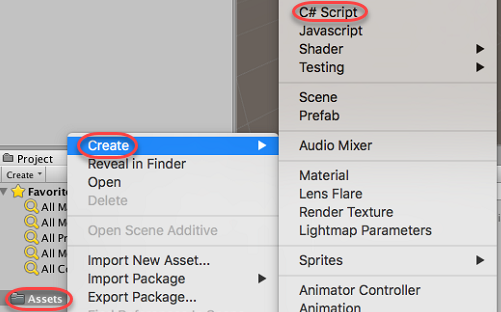

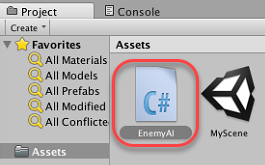

Now you can add some code to drive the enemy logic so that it pursues the player. Right-click the Assets folder in the Project window and select Create > C# Script.

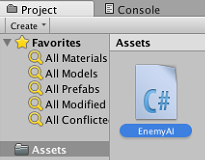

Name the new C# script "EnemyAI".

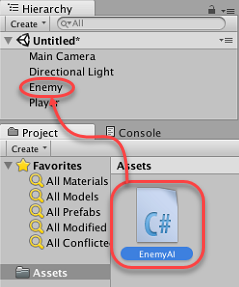

To attach scripts to game objects drag the newly created script onto the Enemy object in the Hierarchy pane. Now that object will use behaviors from this script.

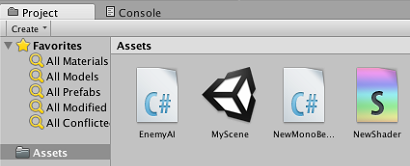

Select File > Save Scenes to save the current scene. Name it "MyScene".

Task 2: Working with Visual Studio for Mac Tools for Unity

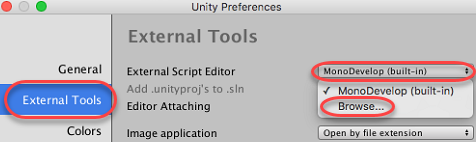

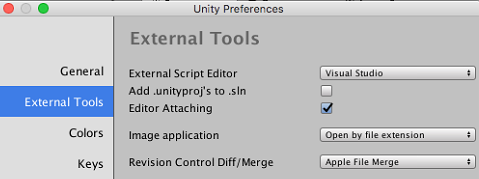

The best way to edit C# code is to use Visual Studio for Mac. You can configure Unity to use Visual Studio for Mac as its default handler. Select Unity > Preferences.

Select the External Tools tab. From the External Script Editor dropdown, select Browse and select Applications/Visual Studio.app. Alternatively, if there's already a Visual Studio option, just select that.

Unity is now configured to use Visual Studio for Mac for script editing. Close the Unity Preferences dialog.

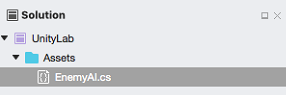

Double-click EnemyAI.cs to open it in Visual Studio for Mac.

The Visual Studio solution is straightforward. It contains an Assets folder (the same one from Finder) and the EnemyAI.cs script created earlier. In more sophisticated projects, the hierarchy will likely look different from what you see in Unity.

EnemyAI.cs is open in the editor. The initial script just contains stubs for the Start and Update methods.

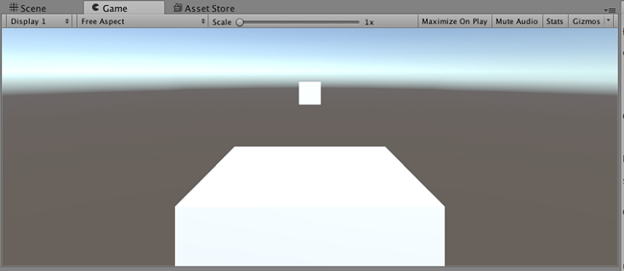

Replace the initial enemy code with the code below.

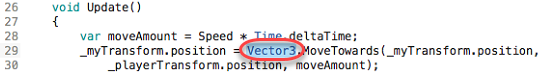

public class EnemyAI : MonoBehaviour { public float Speed = 50; private Transform _playerTransform; private Transform _myTransform; void Start() { var player = GameObject.FindGameObjectWithTag("Player"); if (!player) { Debug.LogError( "Could not find the main player. Ensure it has the player tag set."); } else { _playerTransform = player.transform; } _myTransform = this.transform; } void Update() { var moveAmount = Speed * Time.deltaTime; _myTransform.position = Vector3.MoveTowards(_myTransform.position, _playerTransform.position, moveAmount); if (_myTransform.position == _playerTransform.position) { _myTransform.position = Vector3.back * 10; } } }Take a quick look at the simple enemy behavior that is defined here. In the Start method, we get a reference to the player object (by its tag), and its transform. In the Update method, which is called every frame, the enemy will move towards the player object. The keywords and names use color coding to make it easier to understand the codebase in Visual Studio for Mac.

Save the changes to the enemy script in Visual Studio for Mac.

Task 3: Debugging the Unity project

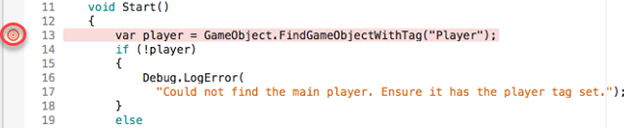

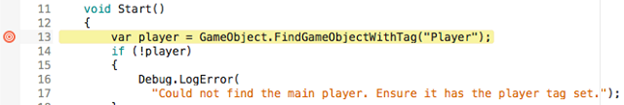

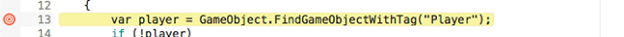

Set a breakpoint on the first line of code in the Start method. You can either click in the editor margin at the target line or place cursor on the line, and then press F9.

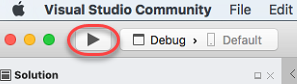

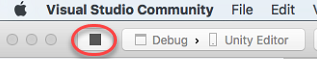

Select the Start Debugging button or press F5. This will build the project and attach it to Unity for debugging.

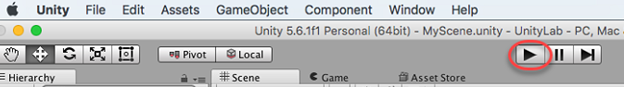

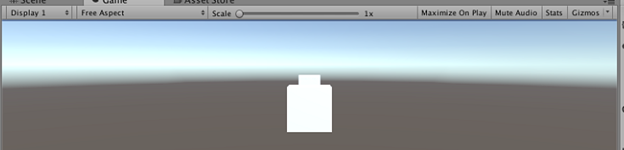

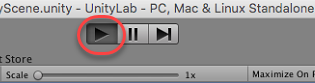

Return to Unity and select the Run button to start the game.

The breakpoint should be hit and you can now use the Visual Studio for Mac debugging tools.

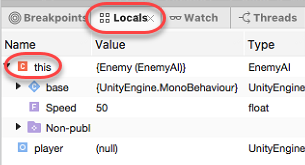

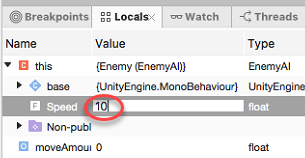

From the Locals window, locate the this pointer, which references an EnemyAI object. Expand the reference and see that you can browse the associated members like Speed.

Remove the breakpoint from the Start method the same way it was added, either by selecting it in the editor margin or by selecting the line, and then pressing F9.

Press F10 to step over the first line of code that finds the Player game object using a tag as parameter.

Hover the mouse cursor over the player variable within the code editor window to view its associated members. You can even expand the overlay to view child properties.

Press F5 or press the Run button to continue execution. Return to Unity to see the enemy cube repeatedly approach the player cube. You may need to adjust the camera if it's not visible.

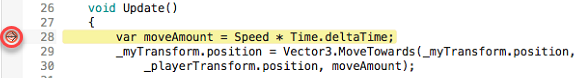

Switch back to Visual Studio for Mac and set a breakpoint on the first line of the Update method. It should be hit immediately.

Suppose the speed is too fast and we want to test the impact of the change without restarting the app. Locate the Speed variable within the Autos or Locals window and then change it to "10" and press Enter.

Remove the breakpoint and press F5 to resume execution.

Return to Unity to view the running application. The enemy cube is now moving at a fifth of the original speed.

Stop the Unity app by clicking the Play button again.

Return to Visual Studio for Mac. Stop the debugging session by clicking the Stop button.

Task 4: Exploring Unity features in Visual Studio for Mac

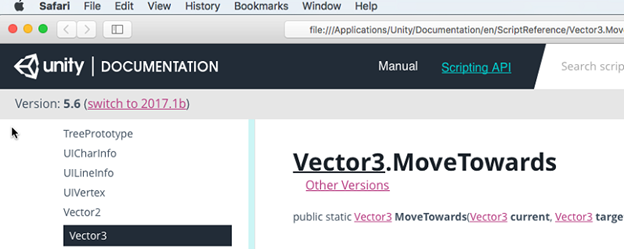

Visual Studio for Mac provides quick access to Unity documentation within the code editor. Place the cursor somewhere on the Vector3 symbol within the Update method and press ⌘ Command + '.

A new browser window opens to the documentation for Vector3. Close the browser window when satisfied.

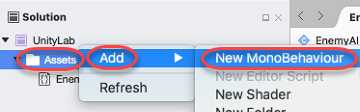

Visual Studio for Mac also provides some helpers to quickly create Unity behavior classes. From Solution Explorer, right-click Assets and select Add > New MonoBehaviour.

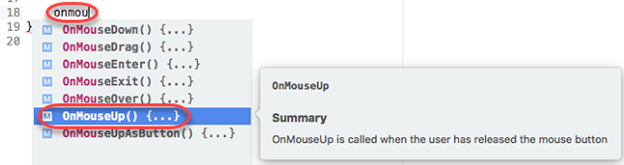

The newly created class provides stubs for the Start and Update methods. After the closing brace of the Update method, start typing "onmouseup". As you type, notice that Visual Studio's IntelliSense quickly zeros in on the method you're planning to implement. Select it from the provided autocomplete list. It will fill out a method stub for you, including any parameters.

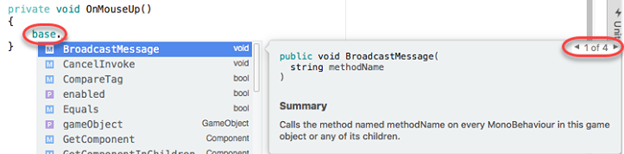

Inside the OnMouseUp method, type "base." to see all of the base methods available to call. You can also explore the different overloads of each function using the paging option in the top-right corner of the IntelliSense flyout.

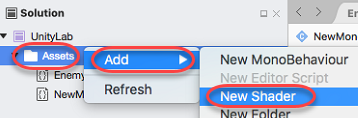

Visual Studio for Mac also enables you to easily define new shaders. From Solution Explorer, right-click Assets and select Add > New Shader.

The shader file format gets full color and font treatment to make it easier to read and understand.

Return to Unity. You'll see that since Visual Studio for Mac works with the same project system, changes made in either place are automatically synchronized with the other. Now it's easy to always use the best tool for the task.

Summary

In this lab, you've learned how to get started creating a game with Unity and Visual Studio for Mac. See https://unity3d.com/learn to learn more about Unity.