Virtual address spaces

Processors use virtual addresses when reading or writing to memory locations. During these operations, the processor translates the virtual address into a physical one.

There are several benefits to accessing memory using virtual addresses:

A program can use a contiguous range of virtual addresses to access a large, noncontiguous memory buffer in physical memory.

A program can use a range of virtual addresses to access a memory buffer larger than the available physical memory. When physical memory is low, the memory manager saves pages of physical memory (typically 4 kilobytes in size) to a disk file. The system moves pages of data or code between physical memory and the disk as needed.

The virtual addresses used by different processes are isolated. The code in one process can't alter the physical memory that is being used by another process or the operating system.

The range of virtual addresses that is available to a process is known as the process's virtual address space. Each user-mode process has its own private virtual address space.

A 32-bit process typically has a virtual address space within the 2-gigabyte range 0x00000000 through 0x7FFFFFFF.

A 64-bit process on 64-bit Windows has a virtual address space within the 128-terabyte range 0x000'00000000 through 0x7FFF'FFFFFFFF.

A range of virtual addresses is sometimes called a range of virtual memory. For more information, see Memory and Address Space Limits.

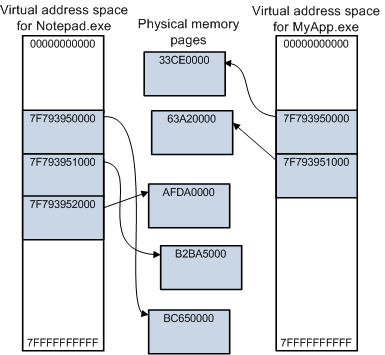

The following diagram illustrates some key features of virtual address spaces.

The diagram shows the virtual address spaces for two 64-bit processes: Notepad.exe and MyApp.exe. Each process has its own virtual address space, ranging from 0x000'0000000 through 0x7FF'FFFFFFFF. Each shaded block represents one page (4 kilobytes in size) of virtual or physical memory. The Notepad process uses three contiguous pages of virtual addresses, starting at 0x7F7'93950000. However, these three contiguous pages of virtual addresses map to noncontiguous pages in physical memory. Also, both processes use a page of virtual memory beginning at 0x7F7'93950000, but these virtual pages map to different pages of physical memory.

User space and system space

Processes like Notepad.exe and MyApp.exe run in user mode. Core operating system components and many drivers run in the more privileged kernel mode. For more information about processor modes, see User mode and kernel mode.

Each user-mode process has its own private virtual address space, but all code that runs in kernel mode shares a single virtual address space called system space. The virtual address space for a user-mode process is called user space.

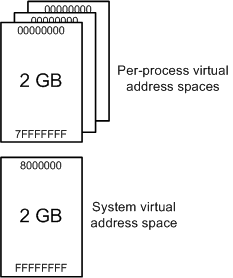

In 32-bit Windows, the total available virtual address space is 2^32 bytes (4 gigabytes). Typically, the lower 2 gigabytes are used for user space, and the upper 2 gigabytes are used for system space.

In 32-bit Windows, you can specify (at boot time) that more than 2 gigabytes are available for user space. However, this means fewer virtual addresses are available for system space. You can increase the size of user space to as much as 3 gigabytes, leaving only 1 gigabyte for system space. To increase the size of user space, use BCDEdit /set increaseuserva.

In 64-bit Windows, the theoretical amount of virtual address space is 2^64 bytes (16 exabytes), but only a small portion of the 16-exabyte range is actually used.

Code running in user mode can access user space but not system space. This restriction prevents user-mode code from reading or altering protected operating system data structures. Code running in kernel mode can access both user space and system space. That is, code running in kernel mode can access system space and the virtual address space of the current user-mode process.

Drivers running in kernel mode must be careful when directly reading from or writing to addresses in user space. The following scenario illustrates why.

A user-mode program initiates a request to read some data from a device. The program provides the starting address of a buffer to receive the data.

A device driver routine, running in kernel mode, starts the read operation and returns control to its caller.

Later, the device interrupts the currently running thread to indicate that the read operation is complete. Kernel-mode driver routines handle the interrupt on this arbitrary thread, which belongs to an arbitrary process.

At this point, the driver must not write the data to the starting address that the user-mode program provided in Step 1. This address is in the virtual address space of the process that initiated the request, which is likely not the same as the current process.

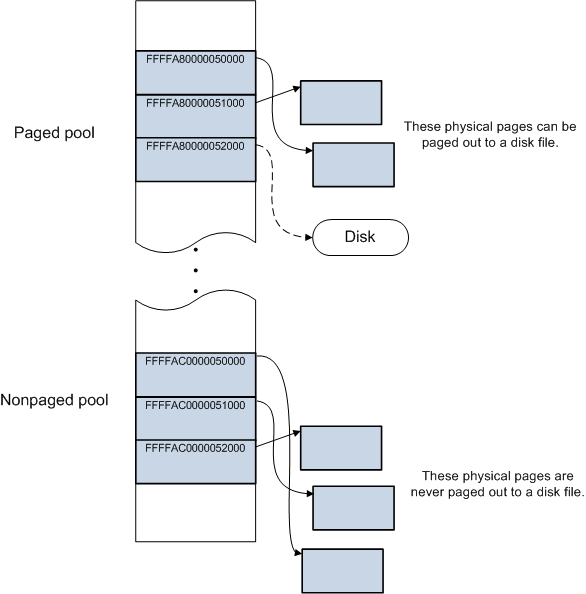

Paged pool and nonpaged pool

In user space, all physical memory pages can be paged out to a disk file as needed. In system space, some physical pages can be paged out and others can't. System space has two regions for dynamically allocating memory: paged pool and nonpaged pool.

Memory that is allocated in paged pool can be paged out to a disk file as needed. Memory that is allocated in nonpaged pool can never be paged out to a disk file.