Control the consumption of resources used by an instance of an application, an individual tenant, or an entire service. This can allow the system to continue to function and meet service level agreements, even when an increase in demand places an extreme load on resources.

Context and problem

The load on a cloud application typically varies over time based on the number of active users or the types of activities they're performing. For example, more users are likely to be active during business hours, or the system might be required to perform computationally expensive analytics at the end of each month. There might also be sudden and unanticipated bursts in activity. If the processing requirements of the system exceed the capacity of the resources that are available, it'll suffer from poor performance and can even fail. If the system has to meet an agreed level of service, such failure could be unacceptable.

There are many strategies available for handling varying load in the cloud, depending on the business goals for the application. One strategy is to use autoscaling to match the provisioned resources to the user needs at any given time. This has the potential to consistently meet user demand, while optimizing running costs. However, while autoscaling can trigger the provisioning of more resources, this provisioning isn't immediate. If demand grows quickly, there can be a window of time where there's a resource deficit.

Solution

An alternative strategy to autoscaling is to allow applications to use resources only up to a limit, and then throttle them when this limit is reached. The system should monitor how it's using resources so that, when usage exceeds the threshold, it can throttle requests from one or more users. This enables the system to continue functioning and meet any service level agreements (SLAs) that are in place. For more information on monitoring resource usage, see the Instrumentation and Telemetry Guidance.

The system could implement several throttling strategies, including:

Rejecting requests from an individual user who's already accessed system APIs more than n times per second over a given period of time. This requires the system to meter the use of resources for each tenant or user running an application. For more information, see the Service Metering Guidance.

Disabling or degrading the functionality of selected nonessential services so that essential services can run unimpeded with sufficient resources. For example, if the application is streaming video output, it could switch to a lower resolution.

Using load leveling to smooth the volume of activity (this approach is covered in more detail by the Queue-based Load Leveling pattern). In a multitenant environment, this approach will reduce the performance for every tenant. If the system must support a mix of tenants with different SLAs, the work for high-value tenants might be performed immediately. Requests for other tenants can be held back, and handled when the backlog has eased. The Priority Queue pattern could be used to help implement this approach, as could exposing different endpoints for the different service levels/priorities.

Deferring operations being performed on behalf of lower priority applications or tenants. These operations can be suspended or limited, with an exception generated to inform the tenant that the system is busy and that the operation should be retried later.

You should be careful when integrating with some 3rd-party services that might become unavailable or return errors. Reduce the number of concurrent requests being processed so that the logs do not unnecessarily fill up with errors. You also avoid the costs that are associated with needlessly retrying the processing of requests that would fail because of that 3rd-party service. Then, when requests are processed successfully, go back to regular unthrottled request processing. One library that implements this functionality is NServiceBus.

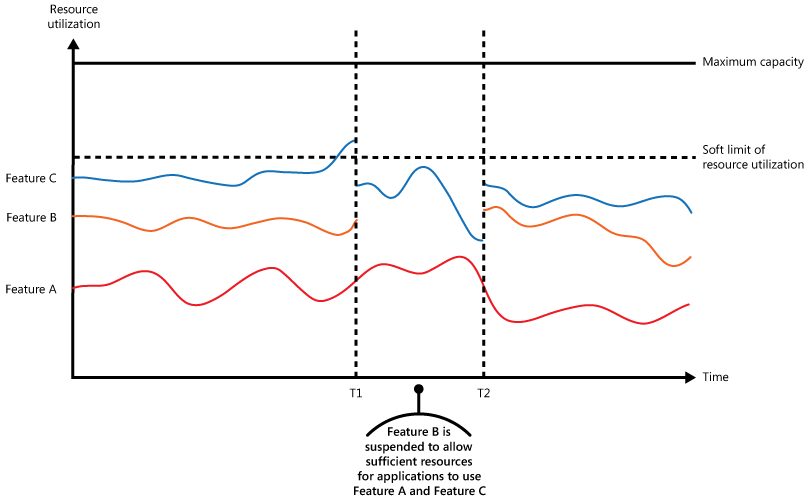

The figure shows an area graph for resource use (a combination of memory, CPU, bandwidth, and other factors) against time for applications that are making use of three features. A feature is an area of functionality, such as a component that performs a specific set of tasks, a piece of code that performs a complex calculation, or an element that provides a service such as an in-memory cache. These features are labeled A, B, and C.

The area immediately below the line for a feature indicates the resources that are used by applications when they invoke this feature. For example, the area below the line for Feature A shows the resources used by applications that are making use of Feature A, and the area between the lines for Feature A and Feature B indicates the resources used by applications invoking Feature B. Aggregating the areas for each feature shows the total resource use of the system.

The previous figure illustrates the effects of deferring operations. Just prior to time T1, the total resources allocated to all applications using these features reach a threshold (the limit of resource use). At this point, the applications are in danger of exhausting the resources available. In this system, Feature B is less critical than Feature A or Feature C, so it's temporarily disabled and the resources that it was using are released. Between times T1 and T2, the applications using Feature A and Feature C continue running as normal. Eventually, the resource use of these two features diminishes to the point when, at time T2, there is sufficient capacity to enable Feature B again.

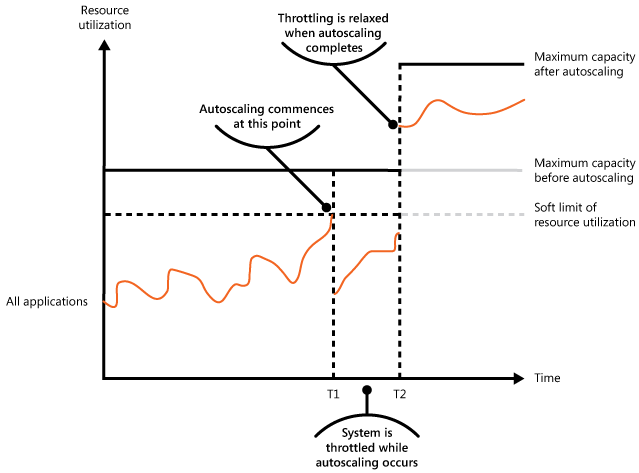

The autoscaling and throttling approaches can also be combined to help keep the applications responsive and within SLAs. If the demand is expected to remain high, throttling provides a temporary solution while the system scales out. At this point, the full functionality of the system can be restored.

The next figure shows an area graph of the overall resource use by all applications running in a system against time, and illustrates how throttling can be combined with autoscaling.

At time T1, the threshold specifying the soft limit of resource use is reached. At this point, the system can start to scale out. However, if the new resources don't become available quickly enough, then the existing resources might be exhausted and the system could fail. To prevent this from occurring, the system is temporarily throttled, as described earlier. When autoscaling has completed and the extra resources are available, throttling can be relaxed.

Issues and considerations

You should consider the following points when deciding how to implement this pattern:

Throttling an application, and the strategy to use, is an architectural decision that impacts the entire design of a system. Throttling should be considered early in the application design process because it isn't easy to add once a system has been implemented.

Throttling must be performed quickly. The system must be capable of detecting an increase in activity and react accordingly. The system must also be able to revert to its original state quickly after the load has eased. This requires that the appropriate performance data is continually captured and monitored.

If a service needs to deny a user request temporarily, it should return a specific error code like 429 ("Too many requests") and 503 ("Server Too Busy") so the client application can understand that the reason for the refusal to serve a request is due to throttling.

- HTTP 429 indicates the calling application sent too many requests in a time window and exceeded a predetermined limit.

- HTTP 503 indicates the service isn't ready to handle the request. The common cause is that the service is experiencing more temporary load spikes than expected.

The client application can wait for a period before retrying the request. A Retry-After HTTP header should be included, to support the client in choosing the retry strategy.

Throttling can be used as a temporary measure while a system autoscales. In some cases, it's better to simply throttle, rather than to scale, if a burst in activity is sudden and isn't expected to be long lived because scaling can add considerably to running costs.

If throttling is being used as a temporary measure while a system autoscales, and if resource demands grow very quickly, the system might not be able to continue functioning—even when operating in a throttled mode. If this isn't acceptable, consider maintaining larger capacity reserves and configuring more aggressive autoscaling.

Normalize resource costs for different operations as they generally don't carry equal execution costs. For example, throttling limits might be lower for read operations and higher for write operations. Not considering the cost of an operation can result in exhausted capacity and exposing a potential attack vector.

Dynamic configuration change of throttling behavior at runtime is desirable. If a system faces an abnormal load that the applied configuration cannot handle, throttling limits might need to increase or decrease to stabilize the system and keep up with the current traffic. Expensive, risky, and slow deployments are not desirable at this point. Using the External Configuration Store pattern throttling configuration is externalized and can be changed and applied without deployments.

When to use this pattern

Use this pattern:

To ensure that a system continues to meet service level agreements.

To prevent a single tenant from monopolizing the resources provided by an application.

To handle bursts in activity.

To help cost-optimize a system by limiting the maximum resource levels needed to keep it functioning.

Workload design

An architect should evaluate how the Throttling pattern can be used in their workload's design to address the goals and principles covered in the Azure Well-Architected Framework pillars. For example:

| Pillar | How this pattern supports pillar goals |

|---|---|

| Reliability design decisions help your workload become resilient to malfunction and to ensure that it recovers to a fully functioning state after a failure occurs. | You design the limits to help prevent resource exhaustion that might lead to malfunctions. You can also use this pattern as a control mechanism in a graceful degradation plan. - RE:07 Self-preservation |

| Security design decisions help ensure the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of your workload's data and systems. | You can design the limits to help prevent resource exhaustion that could result from automated abuse of the system. - SE:06 Network controls - SE:08 Hardening resources |

| Cost Optimization is focused on sustaining and improving your workload's return on investment. | The enforced limits can inform cost modeling and can even be directly tied to the business model of your application. They also put clear upper bounds on utilization, which can be factored into resource sizing. - CO:02 Cost model - CO:12 Scaling costs |

| Performance Efficiency helps your workload efficiently meet demands through optimizations in scaling, data, code. | When the system is under high demand, this pattern helps mitigate congestion that can lead to performance bottlenecks. You can also use it to proactively avoid noisy neighbor scenarios. - PE:02 Capacity planning - PE:05 Scaling and partitioning |

As with any design decision, consider any tradeoffs against the goals of the other pillars that might be introduced with this pattern.

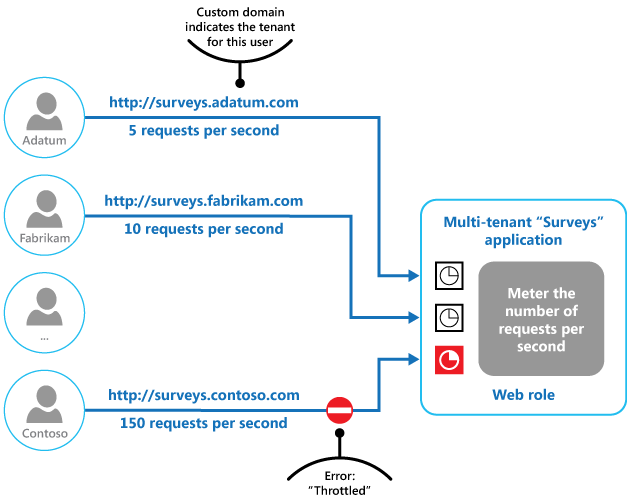

Example

The final figure illustrates how throttling can be implemented in a multitenant system. Users from each of the tenant organizations access a cloud-hosted application where they fill out and submit surveys. The application contains instrumentation that monitors the rate at which these users are submitting requests to the application.

In order to prevent the users from one tenant affecting the responsiveness and availability of the application for all other users, a limit is applied to the number of requests per second the users from any one tenant can submit. The application blocks requests that exceed this limit.

Next steps

The following guidance may also be relevant when implementing this pattern:

- Instrumentation and Telemetry Guidance. Throttling depends on gathering information about how heavily a service is being used. Describes how to generate and capture custom monitoring information.

- Service Metering Guidance. Describes how to meter the use of services in order to gain an understanding of how they're used. This information can be useful in determining how to throttle a service.

- Autoscaling Guidance. Throttling can be used as an interim measure while a system autoscales, or to remove the need for a system to autoscale. Contains information on autoscaling strategies.

Related resources

The following patterns may also be relevant when implementing this pattern:

- Queue-based Load Leveling pattern. Queue-based load leveling is a commonly used mechanism for implementing throttling. A queue can act as a buffer that helps to even out the rate at which requests sent by an application are delivered to a service.

- Priority Queue pattern. A system can use priority queuing as part of its throttling strategy to maintain performance for critical or higher value applications, while reducing the performance of less important applications.

- External Configuration Store pattern. Centralizing and externalizing the throttling policies provides the capability to change the configuration at runtime without the need for a redeployment. Services can subscribe to configuration changes, thereby applying the new configuration immediately, to stabilize a system.