Events

Sep 16, 11 PM - Oct 18, 11 PM

Join us on a learning journey combining AI, apps and cloud-scale data to build unique solutions.

Learn moreThis browser is no longer supported.

Upgrade to Microsoft Edge to take advantage of the latest features, security updates, and technical support.

A good pricing model ensures that you remain profitable as the number of tenants grows and as you add new features. An important consideration when developing a commercial multitenant solution is how to design pricing models for your product. On this page, we provide guidance for technical decision-makers about the pricing models you can consider and the tradeoffs involved.

When you determine the pricing model for your product, you need to balance the return on value (ROV) for your customers with the cost of goods sold (COGS) to deliver the service. Offering more flexible commercial models (for a solution) might increase the ROV for customers, but it might also increase the architectural and commercial complexity of the solution (and therefore also increase your COGS).

Some important considerations that you should take into account, when developing pricing models for a solution, are as follows:

There are some key factors that influence your profitability:

There are many common pricing models that are often used with multitenant solutions. Each of these pricing models has associated commercial benefits and risks, and requires additional architectural considerations. It's important to understand the differences between these pricing models, so that you can ensure your solution remains profitable as it evolves.

Note

You can offer multiple models for a solution or combine models together. For example, you could provide a per-user model for your customers that have fairly stable user numbers, and you can also offer a consumption model for customers who have fluctuating usage patterns.

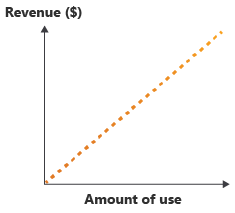

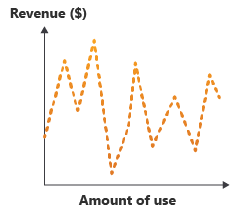

A consumption model is sometimes referred to as pay-as-you-go, or PAYG. As the use of your service increases, your revenue increases:

When you measure consumption, you can consider simple factors, such as the amount of data being added to the solution. Alternatively, you might consider a combination of usage attributes together. Consumption models offer many benefits, but they can be difficult to implement in a multitenant solution.

Benefits: From your customers' perspective, there's minimal upfront investment that's required to use your solution, so that this model has a low barrier to entry. From your perspective as the service operator, your hosting and management costs increase as your customers' usage and your revenue increases. This increase can make it a highly scalable pricing model. Consumption pricing models work especially well when the Azure services that are used in the solution are consumption-based too.

Complexity and operational cost: Consumption models rely on accurate measurements of usage and on splitting this usage by tenant. This can be challenging, especially in a solution with many distributed components. You need to keep detailed consumption records for billing and auditing as well as providing methods for customers to get access to their consumption data.

Risks: Consumption pricing can motivate your customers to reduce their usage of your system, in order to reduce their costs. Additionally, consumption models result in unpredictable revenue streams. You can mitigate this by offering capacity reservations, where customers pay for some level of consumption upfront. You, as the service provider, can use this revenue to invest in improvements in the solution, to reduce the operational cost or to increase the return on value by adding features.

Note

Implementing and supporting capacity reservations may increase the complexity of the billing processes within your application. You might also need to consider how customers get refunds or exchange their capacity reservations, and these processes can also add commercial and operational challenges.

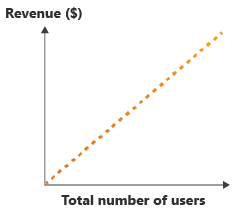

A per-user pricing model involves charging your customers based on the number of people using your service, as demonstrated in the following diagram.

Per-user pricing models are very common, due to their simplicity to implement in a multitenant solution. However, they're associated with several commercial risks.

Benefits: When you bill your customers for each user, it's easy to calculate and forecast your revenue stream. Additionally, assuming that you have fairly consistent usage patterns for each user, then revenue increases at the same rate as service adoption, making this a scalable model.

Complexity and operational cost: Per-user models tend to be easy to implement. However, in some situations, you need to measure per-user consumption, which can help you to ensure that the COGS for a single user remains profitable. By measuring the consumption and associating it with a particular user, you can increase the operational complexity of your solution.

Risks: Different user consumption patterns might result in a reduced profitability. For example, heavy users of the solution might cost more to serve than light users. Additionally, the actual return on value (ROV) for the solution isn't reflected by the actual number of user licenses purchased.

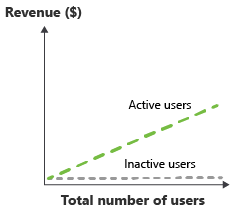

This model is similar to per-user pricing, but rather than requiring an upfront commitment from the customer on the number of expected users, the customer is only charged for users that actually log into and use the solution over a period (as shown in the following diagram).

You can measure this in whatever period makes sense. Monthly periods are common, and then this metric is often recorded as monthly active users or MAU.

Benefits: From your customers' perspective, this model requires a low investment and risk, because there's minimal waste; unused licenses aren't billable. This makes it particularly attractive when marketing the solution or growing the solution for larger enterprise customers. From your perspective as the service owner, your ROV is more accurately reflected to the customer by the number of monthly active users.

Complexity and operational cost: Per-active user models require you to record actual usage, and to make it available to a customer as part of the invoice. Measuring per-user consumption helps to ensure profitability is maintained with the COGS for a single user, but again it requires additional work to measure the consumption for each user.

Risks: Like per-user pricing, there's a risk that the different consumption patterns of individual users may affect your profitability. Compared to per-user pricing, per-active user models have a less predictable revenue stream. Additionally, discount pricing doesn't provide a useful way of stimulating growth.

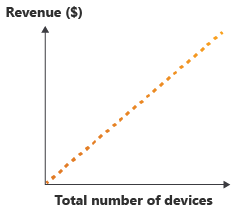

In many systems, the number of users isn't the element that has the greatest effect on the overall COGS. For example, in device-oriented solutions, also referred to as the internet of things or IoT, the number of devices often has the greatest impact on COGS. In these systems, a per-unit pricing model can be used, where you define what a unit is, such as a device. See the following diagram.

Additionally, some solutions have highly variable usage patterns, where a small number of users has a disproportionate impact on the COGS. For example, in a solution sold to brick-and-mortar retailers, a per-store pricing model might be appropriate.

Benefits: In systems where individual users don't have a significant effect on COGS, per-unit pricing is a better way to represent the reality of how the system scales and the resulting impact to COGS. It also can improve the alignment to the actual patterns of usage for a customer. For many IoT solutions, where each device generates a predictable and constant amount of consumption, this can be an effective model to scale your solution's growth.

Complexity and operational cost: Generally, per-unit pricing is easy to implement and has a fairly low operational cost. However, the operational cost can become higher if you need to differentiate and track usage by individual units, such as devices or retail stores. Measuring per-unit consumption helps you ensure your profitability is maintained, since you can determine the COGS for a single unit.

Risks: The risks of a per-unit pricing model are similar to per-user pricing. Different consumption patterns by some units may mean that you have reduced profitability, such as if some devices or stores are much heavier users of the solution than others.

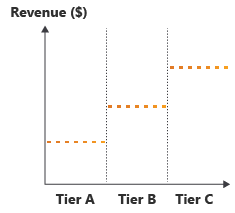

You may choose to offer your solution with different tiers of functionality at different price points. For example, you might provide two monthly flat-rate or per-unit prices, one being a basic offering with a subset of features available, and the other presenting the comprehensive set of your solution's features. See the following diagram.

This model may also offer different service-level agreements for different tiers. For example, your basic tier may offer 99.9% uptime, whereas a premium tier may offer 99.99%. The higher service-level agreement (SLA) could be implemented by using services and features that enable higher availability targets.

Although this model can be commercially beneficial, it does require mature engineering practices to do well. With careful consideration, this model can be very effective.

Benefits: Feature-based pricing is often attractive to customers, since they can select a tier based on the feature set or service level they need. It also provides you with a clear path to upsell your customers with additional features or higher resiliency for those who require it.

Complexity and operational cost: Feature-based pricing models can be complex to implement, since they require your solution to be aware of the features that are available at each price tier. Feature toggles can be an effective way to provide access to certain subsets of functionality, but this requires ongoing maintenance. Also, feature toggles increase the overhead to ensure high quality, because there will be more code paths to test. Enabling higher service availability targets in some tiers may require additional architectural complexity, to ensure the right set of infrastructure is used for each tier, and this process may increase the operational cost of the solution.

Risks: Feature-based pricing models can become complicated and confusing, if there are too many tiers or options. Additionally, the overhead involved in dynamically toggling features can slow down the rate at which you deliver additional features.

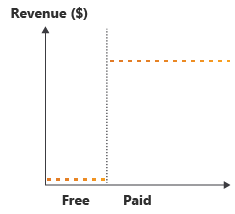

You might choose to offer a free tier of your service, with basic functionality and no service-level guarantees. You then might offer a separate paid tier, with additional features and a formal service-level agreement (as shown in the following diagram).

The free tier may also be offered as a time-limited trial, and during the trial your customers might have full or limited functionality available. This is referred to as a freemium model, which is effectively an extension of the feature-based pricing model.

Benefits: It's very easy to market a solution when it's free.

Complexity and operational cost: All of the complexity and operational cost concerns apply from the feature-based pricing model. However, you also have to consider the operational cost involved in managing free tenants. You might need to ensure that stale tenants are offboarded or removed, and you must have a clear retention policy, especially for free tenants. When promoting a tenant to a paid tier, you might need to move the tenant between Azure services, to obtain higher SLAs. It will also be important to retain the tenant's data and configuration, when moving to a paid tier.

Risks: You need to ensure that you provide a high enough ROV for tenants to consider switching to a paid tier. Additionally, the cost of providing your solution to customers on the free tier needs to be covered by the profit margin from those who are on paid tiers.

You might choose to price your solution so that each tenant only pays the cost of operating their share of the Azure services, with no added profit margin. This model - also called pass through cost or pricing - is sometimes used for multitenant solutions that aren't intended to be a profit center.

The cost of goods sold model is a good fit for internally facing multitenant solutions. Each organizational unit corresponds to a tenant, and the costs of your Azure resources need to be spread between them. It might also be appropriate where revenue is derived from sales of other products and services that consume or augment the multitenant solution.

Benefits: Because this model doesn't include any added margin for profit, the cost to tenants will be lower.

Complexity and operational cost: Similar to the consumption model, cost of goods sold pricing relies on accurate measurements of usage and on splitting this usage by tenant. Tracking consumption can be challenging, especially in a solution with many distributed components. You need to keep detailed consumption records for billing and auditing as well as providing methods for customers to get access to their consumption data.

For internally facing multitenant solutions, tenants might accept approximate cost estimates and have more relaxed billing audit requirements. These relaxed requirements reduce the complexity and cost of operating your solution.

Risks: Cost of goods sold pricing can motivate your tenants to reduce their usage of your system, in order to reduce their costs. However, because this model is used for applications that aren't profit centers, this might not be a concern.

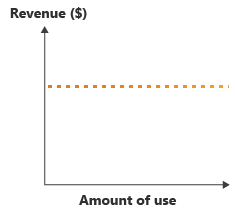

In this model, you charge a flat rate to a tenant for access to your solution, for a given period of time. The same pricing applies regardless of how much they use the service, the number of users, the number of devices they connect, or any other metric. See the following diagram.

This is the simplest model to implement and for customers to understand, and it's often requested by enterprise customers. However, it can easily become unprofitable if you need to continue to add new features or if tenant consumption increases without any additional revenue.

Benefits: Flat-rate pricing is easy to sell, and it's easy for your customers to understand and budget for.

Complexity and operational cost: Flat-rate pricing models can be easy to implement because billing customers doesn't require any metering or tracking consumption. However, while not essential, it's advisable to measure per-tenant consumption to ensure that you're measuring COGS accurately and to ensure that your profitability is maintained.

Risks: If you have tenants who make heavy use of your solution, then it's easy for this pricing model to become unprofitable.

Once you've defined your pricing model, you might choose to implement commercial strategies to incentivize growth through discount pricing. Discount pricing can be used with consumption, per-user, and per-unit pricing models.

Note

Discount pricing doesn't typically require architectural considerations, beyond adding support for a more complex billing structure. A complete discussion into the commercial benefits of discounting is beyond the scope of this document.

Common discount pricing patterns include:

The following diagram illustrates these pricing patterns.

In many cases, customers require access to a non-production environment that they can use for testing, training, or for creating their own internal documentation. Non-production environments usually have lower consumption requirements and costs to operate. For example, non-production environments often aren't subject to service-level agreements (SLAs), and rate limits might be set at lower values. You might also consider more aggressive autoscaling on your Azure services.

Equally, customers often expect non-production environments to be significantly cheaper than their production environments. There are several alternatives that might be appropriate, when you provide non-production environments:

Note

Time-limited trials using freemium tiers aren't usually suitable for testing and training environments. Customers usually need their non-production environments to be available for the lifetime of the production service.

Note

Feature-based pricing is not usually a good option for non-production environments, unless the features offered are the same as what the production environment offers. This is because tenants will usually want to test and provide training on all the same features that are available to them in production.

An unprofitable pricing model costs you more to deliver the service than the revenue you earn. For example, you might charge a flat rate per tenant without any limits for your service, but then you would build your service with consumption-based Azure resources and without per-tenant usage limits. In this situation, you may be at risk of your tenants overusing your service and, thus, making it unprofitable to serve them.

Generally, you want to avoid unprofitable pricing models. However, there are situations where you might choose to adopt an unprofitable pricing model, including:

In the case that you inadvertently create an unprofitable pricing model, there are some ways to mitigate the risks associated with them, including:

When implementing a pricing model for a solution, you'll usually have to make assumptions about how it will be used. If these assumptions turn out to be incorrect or the usage patterns change over time, then your pricing model may become unprofitable. Pricing models that are at risk of becoming unprofitable are known as risky pricing models. For example, if you adopt a pricing model that expects users to self-limit the amount that they use your solution, then you may have implemented a risky pricing model.

Most SaaS solutions will add new features regularly. This increases the ROV to users, which may also lead to increases in the amount the solution is used. This could result in a solution that becomes unprofitable, if the use of new features drives usage, but the pricing model doesn't factor this in.

For example, if you introduce a new video upload feature to your solution, which uses a consumption-based resource, and user uptake of the feature is higher than expected, then consider a combination of usage limits and feature and service level pricing.

Usage limits enable you to restrict the usage of your service in order to prevent your pricing models from becoming unprofitable, or to prevent a single tenant from consuming a disproportionate amount of the capacity of your service. This can be especially important in multitenant services, where a single tenant can impact the experience of other tenants by over-consuming resources.

Note

It's important to make your customers aware that you apply usage limits. If you implement usage limits without making your customers aware of the limit, then it will result in customer dissatisfaction. This means that it's important to identify and plan usage limits ahead of time. The goal should be to plan for the limit, and to then communicate the limits to customers before they become necessary.

Usage limits are often used in combination with feature and service-level pricing, to provide a higher amount of usage at higher tiers. Limits are also commonly used to protect core components that will cause system bottlenecks or performance issues, if they're over-consumed.

A common way to apply a usage limit is to add rate limits to APIs or to specific application functions. This is also referred to as throttling. Rate limits prevent continuous overuse. They're often used to limit the number of calls to an API, over a defined time period. For example, an API may only be called 20 times per minute, and it will return an HTTP 429 error, if it is called more frequently than this.

Some situations, where rate limiting is often used, include the following:

Implementing rate limiting can increase the solution complexity, but services like Azure API Management can make this simpler by applying rate limit policies.

Like any other part of your solution, pricing models have a lifecycle. As your application evolves over time, you might need to change your pricing models. This may be driven by changing customer needs, commercial requirements, or changes to functionality within your application. Some common pricing lifecycle changes include the following:

It is usually complex to implement and manage many different pricing models at once. It's also confusing to your customers. So, it's better to implement only one or two models, with a small number of tiers. This makes your solution more accessible and easier to manage.

Note

Pricing models and billing functions should be tested, ideally using automated testing, just like any other part of your system. The more complex the pricing models, the more testing is required, and so the cost of development and new features will increase.

When changing pricing models, you'll need to consider the following factors:

This article is maintained by Microsoft. It was originally written by the following contributors.

Principal author:

Other contributors:

To see non-public LinkedIn profiles, sign in to LinkedIn.

Consider how you'll measure consumption by tenants in your solution.

Events

Sep 16, 11 PM - Oct 18, 11 PM

Join us on a learning journey combining AI, apps and cloud-scale data to build unique solutions.

Learn moreTraining

Learning path

Solution Architect: Design Microsoft Power Platform solutions - Training

Learn how a solution architect designs solutions.

Certification

Microsoft Certified: Azure Cosmos DB Developer Specialty - Certifications

Write efficient queries, create indexing policies, manage, and provision resources in the SQL API and SDK with Microsoft Azure Cosmos DB.