Note

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try signing in or changing directories.

Access to this page requires authorization. You can try changing directories.

Just as bits are the fundamental object of information in classical computing, qubits (quantum bits) are the fundamental object of information in quantum computing. To understand this correspondence, this article looks at the simplest example: a single qubit.

Representing a qubit

While a bit, or binary digit, can have a value either $0$ or $1$, a qubit can have a value that is either $0$, $1$ or a quantum superposition of $0$ and $1$.

The state of a single qubit can be described by a two-dimensional column vector of unit norm, that is, the magnitude squared of its entries must sum to $1$. This vector, called the quantum state vector, holds all the information needed to describe the one-qubit quantum system just as a single bit holds all of the information needed to describe the state of a binary variable. For the basics of vectors and matrices in quantum computing, see Vector and matrices.

Any two-dimensional column vector of real or complex numbers with norm $1$ represents a possible quantum state held by a qubit. Thus $\begin{bmatrix} \alpha \\ \beta \end{bmatrix}$ represents a qubit state if $\alpha$ and $\beta$ are complex numbers satisfying $|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$.

Some examples of valid quantum state vectors representing qubits are $\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$ and $\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$. These two vectors form a basis for the vector space that describes the qubit's state. This means that any quantum state vector can be written as a sum of these basis vectors. Specifically, the vector $\begin{bmatrix} x \\ y \end{bmatrix}$ can be written as $x \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} + y \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$. While any rotation of these vectors would serve as a perfectly valid basis for the qubit, this particular one is chosen, by calling it the computational basis.

These two quantum states are taken to correspond to the two states of a classical bit, namely $0$ and $1$. The standard convention is to choose

$$0\equiv \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$$ $$1 \equiv \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix},$$

although the opposite choice could equally well be taken. Thus, out of the infinite number of possible single-qubit quantum state vectors, only two correspond to states of classical bits; all other quantum states don't.

Measuring a qubit

How to represent a qubit being explained, one can gain some intuition for what these states represent by discussing the concept of measurement. A measurement corresponds to the informal idea of “looking” at a qubit, which immediately collapses the quantum state to one of the two classical states $\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$ or $\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$. When a qubit given by the quantum state vector $\begin{bmatrix} \alpha \\ \beta \end{bmatrix}$ is measured, the outcome $0$ is obtained with probability $|\alpha|^2$ and the outcome $1$ with probability $|\beta|^2$. On outcome $0$, the qubit's new state is $\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$; on outcome $1$ its state is $\begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$. Note that these probabilities sum up to $1$ because of the normalization condition $|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$.

The properties of measurement also mean that the overall sign of the quantum state vector is irrelevant. Negating a vector is equivalent to $\alpha \rightarrow -\alpha$ and $\beta \rightarrow -\beta$. Because the probability of measuring $0$ and $1$ depends on the magnitude squared of the terms, inserting such signs does not change the probabilities whatsoever. Such phases are commonly called "global phases" and more generally can be of the form $e^{i \phi}$ rather than just $\pm 1$.

A final important property of measurement is that it doesn't necessarily damage all quantum state vectors. If one starts with a qubit in the state $\begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$, which corresponds to the classical state $0$, measuring this state always yields the outcome $0$ and leave the quantum state unchanged. In this sense, if there are only classical bits (for example, qubits that are either $\begin{bmatrix}1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix}$ or $\begin{bmatrix}0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix}$) then measurement doesn't damage the system. This means that one can replicate classical data and manipulate it on a quantum computer just as one could do on a classical computer. The ability, however, to store information in both states at once is what elevates quantum computing beyond what is possible classically and further robs quantum computers of the ability to copy quantum data indiscriminately, see also the no-cloning theorem.

Visualizing qubits and transformations using the Bloch sphere

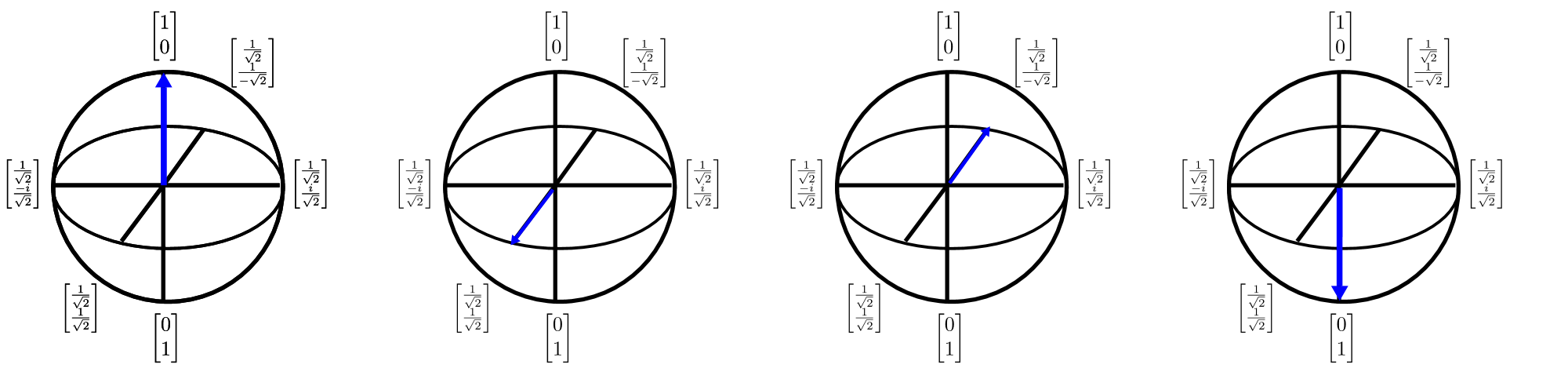

Qubits may also be pictured in $3$D using the Bloch sphere representation. The Bloch sphere gives a way of describing a single-qubit quantum state (which is a two-dimensional complex vector) as a three-dimensional real-valued vector. This is important because it allows us to visualize single-qubit states and thereby develop reasoning that can be invaluable in understanding multi-qubit states (where sadly the Bloch sphere representation breaks down). The Bloch sphere can be visualized as follows:

The arrows in this diagram show the direction in which the quantum state vector is pointing and each transformation of the arrow can be thought of as a rotation about one of the cardinal axes. While thinking about a quantum computation as a sequence of rotations is a powerful intuition, it is challenging to use this intuition to design and describe algorithms. Q# alleviates this issue by providing a language for describing such rotations.

Single-qubit operations

Quantum computers process data by applying a universal set of quantum gates that can emulate any rotation of the quantum state vector. This notion of universality is akin to the notion of universality for traditional (for example, classical) computing where a gate set is considered to be universal if every transformation of the input bits can be performed using a finite length circuit. In quantum computing, the valid transformations that we are allowed to perform on a qubit are unitary transformations and measurement. The adjoint operation or the complex conjugate transpose is of crucial importance to quantum computing because it is needed to invert quantum transformations.

Single-qubit operations, or single-qubit quantum gates can be classified into two categories: Clifford gates and the non-Clifford gates. Non-Clifford gates consist only of $T$-gate (also known as the $\pi/8$ gate).

$$ T=\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & e^{i\pi/4} \end{bmatrix}. $$

The standard set of single-qubit Clifford gates, included by default in Q#, include

$$ H=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 1 \ 1 &-1 \end{bmatrix} , \qquad S =\begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 \ 0 & i \end{bmatrix}= T^2, \qquad X=\begin{bmatrix} 0 &1 \ 1& 0 \end{bmatrix}= HT^4H, $$

$$ Y = \begin{bmatrix} 0 & -i \ i & 0 \end{bmatrix}=T^2HT^4 HT^6, \qquad Z=\begin{bmatrix}1&0\ 0&-1 \end{bmatrix}=T^4. $$

Here the operations $X$, $Y$ and $Z$ are used especially frequently and are named Pauli operators after their creator Wolfgang Pauli. Together with the non-Clifford gate (the $T$-gate), these operations can be composed to approximate any unitary transformation on a single qubit.

While the previous constitute the most popular primitive gates for describing operations on the logical level of the stack (think of the logical level as the level of the quantum algorithm), it is often convenient to consider less basic operations at the algorithmic level, for example operations closer to a function description level. Fortunately, Q# also has methods available for implementing higher-level unitaries, which in turn allow high-level algorithms to be implemented without explicitly decomposing everything down to Clifford and $T$-gates.

The simplest such primitive is the single qubit-rotation. Three single-qubit rotations are typically considered: $R_x$, $R_y$ and $R_z$. To visualize the action of the rotation $R_x(\theta)$, for example, imagine pointing your right thumb along the direction of the $x$-axis of the Bloch sphere and rotating the vector with your hand through an angle of $\theta/2$ radians. This confusing factor of $2$ arises from the fact that orthogonal vectors are $180^\circ$ apart when plotted on the Bloch sphere, yet are actually $90^\circ$ degrees apart geometrically. The corresponding unitary matrices are:

$$ \begin{align*} &R_z(\theta) = e^{-i\theta Z/2} = \begin{bmatrix} e^{-i\theta/2} & 0\\ 0& e^{i\theta/2} \end{bmatrix}, \\ &R_x(\theta) = e^{-i\theta X/2} = HR_z(\theta)H = \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\theta/2) & -i\sin(\theta/2)\\ -i\sin(\theta/2) & \cos(\theta/2) \end{bmatrix}, \\ &R_y(\theta) = e^{-i\theta Y/2} = SHR_z(\theta)HS^\dagger = \begin{bmatrix} \cos(\theta/2) & -\sin(\theta/2)\\ \sin(\theta/2) & \cos(\theta/2) \end{bmatrix}. \end{align*} $$

Just as any three rotations can be combined together to perform an arbitrary rotation in three dimensions, it can be seen from the Bloch sphere representation that any unitary matrix can be written as a sequence of three rotations as well. Specifically, for every unitary matrix $U$ there exists $\alpha,\beta,\gamma,\delta$ such that $U= e^{i\alpha} R_x(\beta)R_z(\gamma)R_x(\delta)$. Thus $R_z(\theta)$ and $H$ also form a universal gate set although it isn't a discrete set because $\theta$ can take any value. For this reason, and due to applications in quantum simulation, such continuous gates are crucial for quantum computation, especially at the quantum algorithm design level. To achieve fault-tolerant hardware implementation, they will ultimately be compiled into discrete gate sequences that closely approximate these rotations.