Networking within datacenters

Large datacenters are part of the core infrastructure that supports cloud services. To be cost-effective, these datacenters must have networks that are agile and easy to configure and update. In previous modules, we looked at some of the enabling physical technologies used in these networks, as well as a general multi-tier topology. In this module, we will look at some design considerations for the network within cloud datacenters, as well as understand how and why software-defined networks (SDNs) have gained prominence in this domain.

Computer networks are a collection of nodes and links. A node can be any network equipment, such as a switch, router, or server. A link is a physical or logical connection between two nodes in the network. Networks also comprise identification resources (addresses) and labeling tags. Often, a mechanism for the management of the identification for devices (IP address and MAC address), links (flow ID), and networks (VLAN ID, VPN ID) is needed for the management and monitoring of a virtualized infrastructure. High-level organizational structures such as a network topologies can be created by assembling these resources. The topics we discuss below are extremely large and complex. This page merely introduces them to convey the need for network virtualization within cloud datacenters.

Challenges and design considerations for datacenter networks

Designers of large datacenter networks have to contend with several (sometimes contradictory) requirements.1 They must:

- Ensure that the topology used is scalable to cope with future demand.

- Maximize throughput while minimizing hardware cost.

- Ensure their design guarantees availability and integrity of the system despite failures.

- Implement power-saving features to reduce operating costs (and be environment-friendly).

An important consideration in designing the network for a large datacenter relies on selecting the right network fabric (or combination), among Ethernet, InfiniBand, and other high-speed fabrics like Myrinet. Each one has different cost, latency, bandwidth, and communication criteria and must be chosen carefully. A physical comparison of these fabrics is not within our scope. What interests us more is the topology and addressing scheme selected to interconnect these resources. For instance, if we choose to use an Ethernet-addressed network (where endpoints are identified based on a flat 6-byte MAC address), it is likely that such a network will be flat, where each interface is assigned a MAC address that does not depend upon its location. This makes routing difficult and forwarding tables large, since all addresses must be stored.

For this reason, we mostly rely on hierarchical routing to build scalable networks. As we discussed earlier, most datacenters rely on top-of-rack (ToR) switches interconnected through end-of-row (EoR) switches. Addressing and routing are often based on IP-based routing, where each endpoint is assigned an IP address based on its location in the hierarchy. However, this introduces restrictions in a cloud datacenter, by limiting the mobility of a virtual machine (VM)—migrating a VM from one host to another must be handled using a different policy. Also, as we have seen in our discussion about security, it is often problematic to allocate IP addresses deterministically in a public cloud environment, as it reveals information about co-location. The selection of datacenter network topologies is an active area of research, with the focus on both fixed and flexible topologies that could be tree-based or recursive.

Apart from the topology and addressing scheme, it is important to decide on the routing mechanism. Routing may be centralized, where a single central controller creates lookup tables that determine the forwarding action. This is theoretically optimal, since the central controller has complete visibility of the datacenter network, and makes it easier to configure and to understand the impact of faults. However, the controller introduces a bottleneck and single point of failure, and results in a substantial overhead in propagating forwarding tables. Instead of centralized routing, distributed approaches may be used where decisions are based upon local information at each router and switch.

Traffic within large datacenters may be carefully engineered to reduce congestion and latency. To do this, groups of packets are categorized as "flows" if they are sequentially or logically related. The routing protocols above perform load balancing by distributing these as a flow between two nodes among multiple parallel paths. The design of a datacenter must be optimized for the specific flow patterns within it, which is why the ability to analyze traffic is important for a datacenter designer. Routing protocols must be state-aware, so that idle routes are favored over busy ones, and flows are dispersed over multiple parallel paths.

Finally, datacenter networks must be designed for fault tolerance. Such networks often use gossip protocols, where neighbors talk to each other to disseminate information about failures quickly. It is important to design such mechanisms to not use a large amount of bandwidth. There must also be mechanisms to recover from failure and re-incorporate failed components within the network.

Virtualization in cloud datacenter networks

By now, it should be clear that implementing a large datacenter network is extremely complex and needs a higher-level abstraction to be easy to design and configure. However, the situation is even more complex for cloud datacenters, largely due to multi-tenancy requirements. The cloud computing paradigm is relevant only if it can ensure isolation among multiple tenants. A cloud service provider (CSP) must ensure traffic isolation, so that one tenant's traffic is not visible to another. The address space must also be isolated, so that each tenant has access to their own private address space.

Both traffic and address-space isolation are achieved by building "virtual networks" for each tenant, and traffic between these networks is restricted to a few strictly defined points. These virtual networks are generally built as an "overlay" on top of the real (physical) network. We refer to network virtualization as the process of provisioning these overlays, associating them with the tenant's network interfaces, and maintaining the lifecycle of this network as VM instances are launched, stopped, or terminated.2

An overlay network is a virtual network in which the separation of tenants is hidden from the underlying physical infrastructure, such that the underlying transport network does not need to know about the different tenants to correctly forward traffic.

One of the important benefits of virtualizing the network is that it allows VM migration between hosts while retaining its network state (IP and MAC addresses). Changes in MAC addresses can cause many unexpected disruptions, for example by invalidating software licenses. Thus, physical hosts can be assigned IP addresses hierarchically, whereas VMs can have an IP address that is within a pool of valid addresses for that subnet.

Another driver for virtualization is the increased complexity in maintaining forwarding tables. Instead of a single MAC address per physical server, cloud datacenters will have to maintain the MAC address of up to hundreds of VM instances per server, which leads to significant demand on the forwarding node's capacity.

Virtualization also helps provide individual tenants with control over the addresses they use within their view of the network. Thus, the overlay network must provide tenants access to use any address that they want, without having to check the networks of all of the neighboring tenants. These addresses should also be independent of the addresses used by the CSP's infrastructure. Virtual networks use this address separation to limit the scope of packets that are sent on it. Packets are allowed to cross network boundaries only through controlled exit points.

Finally, the presence of multiple tenants and the overcommitting of the shared network bandwidth lead to a traffic and flow management challenge. CSPs must ensure a QoS in line with the guaranteed SLAs and must shape traffic from each tenant according to the peak utilization provisioned.

Types of network virtualization

As we have seen above, network virtualization is simply a sharing mechanism that allows multiple isolated virtual networks to use the same physical network infrastructure. This allows virtual networks to be dynamically allocated and deployed on demand, precisely like VMs in virtualized servers.3

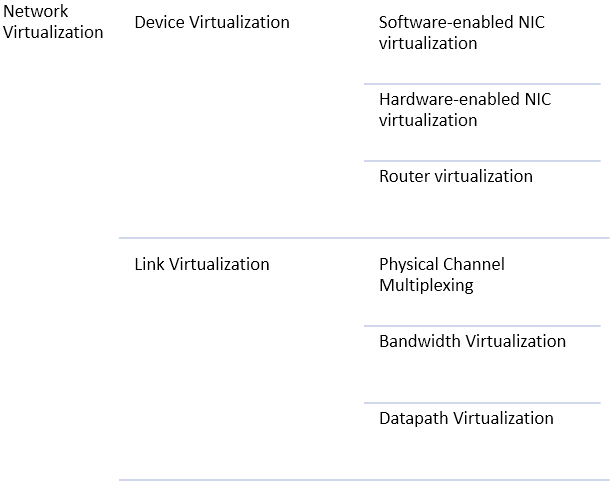

Figure 1: Types of network virtualization

Network virtualization is a broad term that encompasses many different techniques. For example, traditional VPNs and VLANs are types of data-path virtualization, where a physical link is extended virtually. Cloud datacenters rely on a combination of all of these virtualization techniques to build a scalable, flexible, and agile network. Virtual machines have virtualized network interface cards, which bridge a unique virtual MAC address to the physical NIC. Router virtualization enables the creation of multiple tenant virtual networks based on "map-and-encap," where edge routers map the packet to the destination, and then encapsulate packets within a network tunnel that are decoded only at the target node.

Bandwidth and physical channel virtualization are achieved by sharing slots within the network using traditional techniques like TDM/FDM and circuit switching. Data-path virtualization allows packets to travel along a programmable path, allowing flexible flows and traffic management. In the coming pages, we will also explore SDNs, which are an alternative to simple network virtualization.

In conclusion, cloud datacenters rely on a group of techniques to decouple network services from the hardware network, making it easy to programmatically configure and deploy them.

References

- Liu, Yang and Muppala, Jogesh K and Veeraraghavan, Malathi and Lin, Dong and Hamdi, Mounir (2013). Data Center Networks: Topologies, Architectures and Fault-Tolerance Characteristics Springer Science and Business Media

- Liu, Yang and Muppala, Jogesh K and Veeraraghavan, Malathi and Lin, Dong and Hamdi, Mounir (2014). Problem statement: Overlays for network virtualization RFC 7364

- Wen, Heming and Tiwary, Prabhat Kumar and Le-Ngoc, Tho (2013). Wireless virtualization Springer