What is object-oriented programming?

Object-oriented programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm. It's based on the idea of grouping related data and functions into "islands" of information. These islands are known as objects.

No matter which paradigm is used, programs use the same series of steps to solve problems:

- Data input: Data is read from somewhere, which could be data storage like a file system or a database.

- Processing: Data is interpreted and possibly altered to be prepared for display.

- Data output: Data is presented so that it can be read and interacted with either by a physical user or a system.

OOP vs. procedural programming

Let's try to define what OOP is by comparing it to another paradigm: procedural programming. Procedural programming sets out to solve a given problem by calling procedures, also known as functions or methods. Functions and variables are constructed to address the various phases described in the preceding steps.

The OOP paradigm is no different in that aspect. What makes it stand out is how it looks at the world. Compared to procedural programming, OOP takes a step back and looks at the bigger picture. Instead of working on data and taking it from one phase to the next, OOP tries to understand the world in which the data operates. It does so by modeling what it sees.

OOP modeling: Identify concepts

During the modeling phase, you look at a description of a domain and try to analyze the text on what takes place. The first step is to identify actors. They're called actors because they act and perform an action. For example, a printer (actor) prints (action).

After you identify actors, you look at what they do, which is their behavior. Then you look at descriptions of the actors and any data that's needed to carry out the action. Actors are made into objects, the traits are encoded as data on the objects, and the behaviors are functions that also get added to the object.

The idea is that data on objects can be altered by calling functions on the objects themselves. There's also the notion that objects interact with one another to achieve a tangible result.

Benefits of OOP

So why use OOP? Why not use some other paradigm? To be clear, OOP isn't better or worse than any other paradigm. There are pros and cons to everything. OOP does have some nice benefits, for example:

- Data encapsulation: Data encapsulation is about hiding data away from the rest of the system and only allowing access to parts of it. The reason is data holds state, and that state can be made up of one or more variables. If these variables need to be changed at the same time, you need to protect them and only allow access via public methods so that changes are made in a predictable way. OOP has mechanisms like access levels, where data that's on an object can only be accessed by the object itself or can be made publicly available.

- Simplicity: Building large systems is a complex task, with many problems to solve. Being able to break down the complexity into smaller problems, to objects, means you can simplify the overall task.

- Easy to modify: When you rely on objects and model your system with them, it's easier to track down what parts of the system need modifying. For example, you might need to correct a bug or add a new feature.

- Maintainability: Maintaining code in general is hard, and it becomes harder over time. It requires discipline in the form of good naming and a clear and consistent architecture, among other considerations. Using objects makes it easier to locate a specific area of your code that needs maintaining.

- Reusability: You can use an object's definition many times in many parts of your system, or potentially in other systems too. When you reuse code, you save time and money because you need to write less code and you reach your target faster.

Model an OOP system

Software is often written to address a need to make something faster, more efficient, and less error prone. People simply can't compete with software when it comes to speeding up a process in certain cases. Using OOP is as much a modeling exercise as it is about writing the code to implement its logic. Modeling is about learning to identify the actors, the data needed, and the type of interaction taking place. You can model a system just by reading a description of it.

Invoice management system case study

Let's look at a manual flow that many companies struggle with, namely invoice management. Many companies receive invoices, and they need to be paid on time. Late payments incur late fees, which result in wasted money. Before an invoice can be paid, it must be processed. It's common for an invoice to pass through a few hands before it ends up being registered somewhere and payment is made.

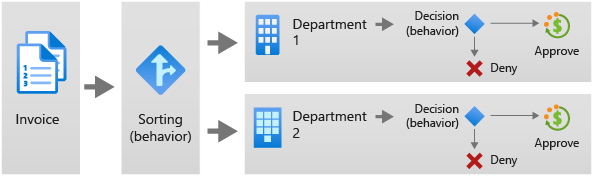

The process usually starts with an initial sorting phase, where the invoice is sent to the appropriate department. Next, the invoice is checked for correctness and then approved by someone who has the proper authorization level. Lastly, the invoice is paid. For a small business, the business owner might do all of the steps. In a large company, many people and processes might be involved, which makes invoice management a complex activity.

What does this description have to do with OOP? If you took the preceding workflow — which is often a manual flow — and turned it into written software, the first thing you would do is try to model the system. With the context of invoice management, you can start seeing actors (objects), behaviors, and data by reading a description of the problem domain.

If you think about the described domain as having phases, input, processing, and output, you can start to fill things in like in the following table:

| Phase | What |

|---|---|

| Input | Invoice |

| Processing | Sorting, Approval, Rejection |

| Output | Payment |

The preceding table describes what goes on at each phase. You've been able to find the data, things that happen to the data during processing, and the ultimate result, which is a payment. At this point, you can still solve the invoice management system workflow with any paradigm you like. How do you take it from here into OOP?

Find objects, data, and behavior

You find the different artifacts of your system by asking questions like:

- Who interacts with whom?

- Who does what to whom?

With such questions in mind, you can come up with statements. Let's highlight the different artifacts in these statements so it becomes clear what parts are important to our system.

The mail service delivers an invoice to the system.

The invoice is sorted by either a reference code or manually by a sorter to ensure it ends up in the correct department.

The invoice is approved or rejected by an approver based on factors like (for example) correctness and size of the amount.

The invoice is paid by a payment processor by using the payment information provided.

You can now extract objects, data, and behavior from the sentences and organize them in a table, like so:

| Phase | Actor | Behavior | Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input | Mail service | Delivers | Invoice |

| Input | System | Receives | Invoice |

| Processing | Sorters or system | Sorts or routes | Invoice (reference code) |

| Processing | Approver | Approves or rejects | Invoice (amount) |

| Output | Payment processor | Pays | Invoice (payment information) |

A lot has happened to the initial description of the invoice management system. Actors (objects) have been found. Important data has been identified and grouped with identified objects. Behavior has also been found, which makes it clearer what actors (objects) interact with one another. As a result, you've been able to pinpoint who does what behavior to whom. You've done an initial analysis at this point, which is a great start. But the question remains, how do you turn this analysis into code? The answer to that question is what we will be solving throughout this module.

Note

An actual invoice management system is likely a lot more complex and could rely on much more data and logic. Being able to model a system this way means you have a structured approach to think about the problem.