Use classes and variables to transfer your OOP model into code

You want to evaluate object-oriented programming (OOP) by building the game rock, paper, scissors. To do so, you first need to model it in an OOP format.

We'll need to apply some fundamental OOP concepts, such as classes, objects, and state. This unit explores the following parts:

- Important OOP concepts: To reason in OOP, you need to understand some fundamental concepts like classes, objects, and state. You need to know what the difference is between them and how they relate to one another.

- Variables in OOP: You need to know how to deal with variables and how to add them to your objects.

What is an object?

The concept of objects has been mentioned a few times already as part of trying to model problem domains. An object is an actor. It's something that does something within a system. As a result of taking an action, it changes state within itself or other objects.

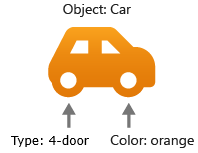

Let's imagine an object in the real world. You're in a car park; what do you see? You're likely to see many cars, in different shapes, sizes, and colors. To describe a car, you can use properties like make, model, color, and type of car. If you assign values to these properties, it quickly becomes clear whether you're talking about a red Ferrari, or a four-wheel-drive Jeep, or a yellow Mustang, and so on.

In another scene, picture a deck of cards in Las Vegas. You look at two different cards, which are two objects. You realize they have some common properties, namely, suit. The suit for the objects can be clubs, hearts, diamonds, or spades. Their values can be ace, king, nine, and so on.

Tip

Look at your surroundings. Take two similar objects, like two books or two chairs, and see if you can find the properties that best describe them and tell them apart.

What is a class?

A class is a data type that acts as a template definition for a particular kind of object.

You've learned that an OOP system has objects, and those objects have properties. There's a concept that's similar to an object: namely, a class.

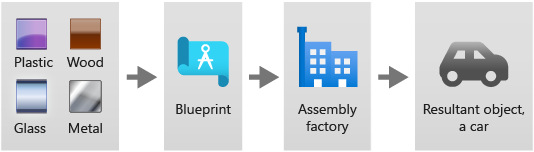

So, what's a class? A class is a blueprint of an object. Where the class is the blueprint of a car, the object is the actual car you drive around. The class is what you write in code. The object is what you get when you tell the runtime environment to run your code.

Here's a table of some examples of classes and their resulting objects:

| Class | Object |

|---|---|

| Blueprint of a car | Honda Accord, Jeep Wrangler |

| Cat | Garfield the cat |

| Description of ice cream | Strawberry, chocolate, or vanilla |

The way you go about creating an object from a class is similar to how you would create a car from a blueprint. When you create an object, your program asks the operating system for resources, namely memory, to be able to construct the object. Conversely, when a car is made from a blueprint, the factory asks for resources like metal, rubber, and glass to be able to assemble the car.

Create a class

A class in Python is created by using the keyword class and giving it a name, like in this example:

class Car:

Create an object from a class

When you create an object from a class, you're said to instantiate it. What you're doing is asking the operating system, with this template (the class) and these starter values, to give you enough memory and create an object. Essentially, instantiate is another word for create.

To instantiate an object, you add parentheses to the name of the class. What you get is an object that you can choose to assign to a variable, like so:

car = Car()

The car is the variable that holds your object's instance. The moment of instantiation, or object creation, is when you call Car().

Variables in OOP vs. variables in procedural programs

From procedural programming, you're used to having variables to hold information and keep track of state. You can define these variables wherever you need them in your file. The typical variable initialization can look like so:

pi = 3.14

You have variables in OOP too, although they're attached to objects instead of being defined on their own. You refer to variables on an object as attributes. When an attribute is attached to an object, it's used in one of two ways:

- Describe the object: An example of a description variable is, for example, the color of a car or the number of spots on a giraffe.

- Hold the state: A variable can instead be used to describe an object's state. An example of a state is the floor of an elevator, or whether it's running or not.

Add attributes to a class

Knowing what attributes (variables) should be added to your class is part of modeling. You've learned how to create a class in code, so how do you add an attribute to it? You need to tell the class what attributes it should have at construction time, when an object is being instantiated. There's a special function that's being called at the moment of creation, called a constructor.

Constructor

Many program languages have the notion of a constructor, the special function that's only invoked when the object is first being created. The constructor will be called only once. In this method, you create the attributes the object should have. Additionally, you assign any starter values to the created attributes.

In Python, the constructor has the name __init__(). You also need to pass a special parameter, self, to the constructor. The parameter self refers to the object's instance. Any assignment to this keyword means that the attribute ends up on the object instance. If you don't add an attribute to self, it will instead be treated as a temporary variable that won't exist after __init__() is done executing.

Note

The parameter self will also need to be passed to any methods that need to refer to anything on the object instance. This concept will be covered in the next unit.

Add and initialize attributes on a class

Let's see an example of setting up attributes in a constructor:

class Elevator:

def __init__(self, starting_floor):

self.make = "The elevator company"

self.floor = starting_floor

# To create the object

elevator = Elevator(1)

print(elevator.make) # "The Elevator company"

print(elevator.floor) # 1

The preceding example describes the class Elevator with two variables, make and floor. An important takeaway from the code is that __init__() is called implicitly. You don't call the __init__() method by name, but it's called when the object is created, in this line of code:

elevator = Elevator(1)

Incorrect use of self

To emphasize how the parameter self works, consider the following code in which two attributes, color and make, are being assigned in the constructor __init__():

class Car:

def __init__():

self.color = "Red" # ends up on the object

make = "Mercedes" # becomes a local variable in the constructor

car = Car()

print(car.color) # "Red"

print(car.make) # would result in an error, `make` does not exist on the object

If the purpose was to make both color and make attributes of the class Car, you would need to modify the code. In the constructor, ensure both attributes are assigned to self, like so:

self.color = "Red" # ends up on the object

self.make = "Mercedes"

Tip

As a home exercise, try creating a class from a book you would read. Think about how you would write its class and what properties it should have.