Nóta

Aðgangur að þessari síðu krefst heimildar. Þú getur prófað aðskrá þig inn eða breyta skráasöfnum.

Aðgangur að þessari síðu krefst heimildar. Þú getur prófað að breyta skráasöfnum.

You can avoid performance bottlenecks and enhance the overall responsiveness of your application by using asynchronous programming. However, traditional techniques for writing asynchronous applications can be complicated, making them difficult to write, debug, and maintain.

C# supports simplified approach, async programming, that uses asynchronous support in the .NET runtime. The compiler does the difficult work that the developer used to do, and your application retains a logical structure that resembles synchronous code. As a result, you get all the advantages of asynchronous programming with a fraction of the effort.

This article provides an overview of when and how to use async programming and includes links to other articles that contain details and examples.

Async improves responsiveness

Asynchrony is essential for activities that are potentially blocking, such as web access. Access to a web resource sometimes is slow or delayed. If such an activity is blocked in a synchronous process, the entire application must wait. In an asynchronous process, the application can continue with other work that doesn't depend on the web resource until the potentially blocking task finishes.

The following table shows typical areas where asynchronous programming improves responsiveness. The listed APIs from .NET and the Windows Runtime contain methods that support async programming.

| Application area | .NET types with async methods | Windows Runtime types with async methods |

|---|---|---|

| Web access | HttpClient | Windows.Web.Http.HttpClient SyndicationClient |

| Working with files | JsonSerializer StreamReader StreamWriter XmlReader XmlWriter |

StorageFile |

| Working with images | MediaCapture BitmapEncoder BitmapDecoder |

|

| WCF programming | Synchronous and Asynchronous Operations |

Asynchrony proves especially valuable for applications that access the UI thread because all UI-related activity usually shares one thread. If any process is blocked in a synchronous application, all are blocked. Your application stops responding, and you might conclude that it failed when instead it's just waiting.

When you use asynchronous methods, the application continues to respond to the UI. You can resize or minimize a window, for example, or you can close the application if you don't want to wait for it to finish.

The async-based approach adds the equivalent of an automatic transmission to the list of options that you can choose from when designing asynchronous operations. That is, you get all the benefits of traditional asynchronous programming but with much less effort from the developer.

Async methods are easy to write

The async and await keywords in C# are the heart of async programming. By using those two keywords, you can use resources in .NET Framework, .NET Core, or the Windows Runtime to create an asynchronous method almost as easily as you create a synchronous method. Asynchronous methods that you define by using the async keyword are referred to as async methods.

The following example shows an async method. Almost everything in the code should look familiar to you.

You can find a complete Windows Presentation Foundation (WPF) example available for download from Asynchronous programming with async and await in C#.

public async Task<int> GetUrlContentLengthAsync()

{

using var client = new HttpClient();

Task<string> getStringTask =

client.GetStringAsync("https://learn.microsoft.com/dotnet");

DoIndependentWork();

string contents = await getStringTask;

return contents.Length;

}

void DoIndependentWork()

{

Console.WriteLine("Working...");

}

You can learn several practices from the preceding sample. Start with the method signature. It includes the async modifier. The return type is Task<int> (See "Return Types" section for more options). The method name ends in Async. In the body of the method, GetStringAsync returns a Task<string>. That means that when you await the task you get a string (contents). Before awaiting the task, you can do work that doesn't rely on the string from GetStringAsync.

Pay close attention to the await operator. It suspends GetUrlContentLengthAsync:

GetUrlContentLengthAsynccan't continue untilgetStringTaskis complete.- Meanwhile, control returns to the caller of

GetUrlContentLengthAsync. - Control resumes here when

getStringTaskis complete. - The

awaitoperator then retrieves thestringresult fromgetStringTask.

The return statement specifies an integer result. Any methods that are awaiting GetUrlContentLengthAsync retrieve the length value.

If GetUrlContentLengthAsync doesn't have any work that it can do between calling GetStringAsync and awaiting its completion, you can simplify your code by calling and awaiting in the following single statement.

string contents = await client.GetStringAsync("https://learn.microsoft.com/dotnet");

The following characteristics summarize what makes the previous example an async method:

The method signature includes an

asyncmodifier.The name of an async method, by convention, ends with an "Async" suffix.

The return type is one of the following types:

- Task<TResult> if your method has a return statement in which the operand has type

TResult. - Task if your method has no return statement or has a return statement with no operand.

voidif you're writing an async event handler.- Any other type that has a

GetAwaitermethod.

For more information, see the Return types and parameters section.

- Task<TResult> if your method has a return statement in which the operand has type

The method usually includes at least one

awaitexpression, which marks a point where the method can't continue until the awaited asynchronous operation is complete. In the meantime, the method is suspended, and control returns to the method's caller. The next section of this article illustrates what happens at the suspension point.

In async methods, you use the provided keywords and types to indicate what you want to do, and the compiler does the rest, including keeping track of what must happen when control returns to an await point in a suspended method. Some routine processes, such as loops and exception handling, can be difficult to handle in traditional asynchronous code. In an async method, you write these elements much as you would in a synchronous solution, and the problem is solved.

For more information about asynchrony in previous versions of .NET Framework, see TPL and traditional .NET Framework asynchronous programming.

What happens in an async method

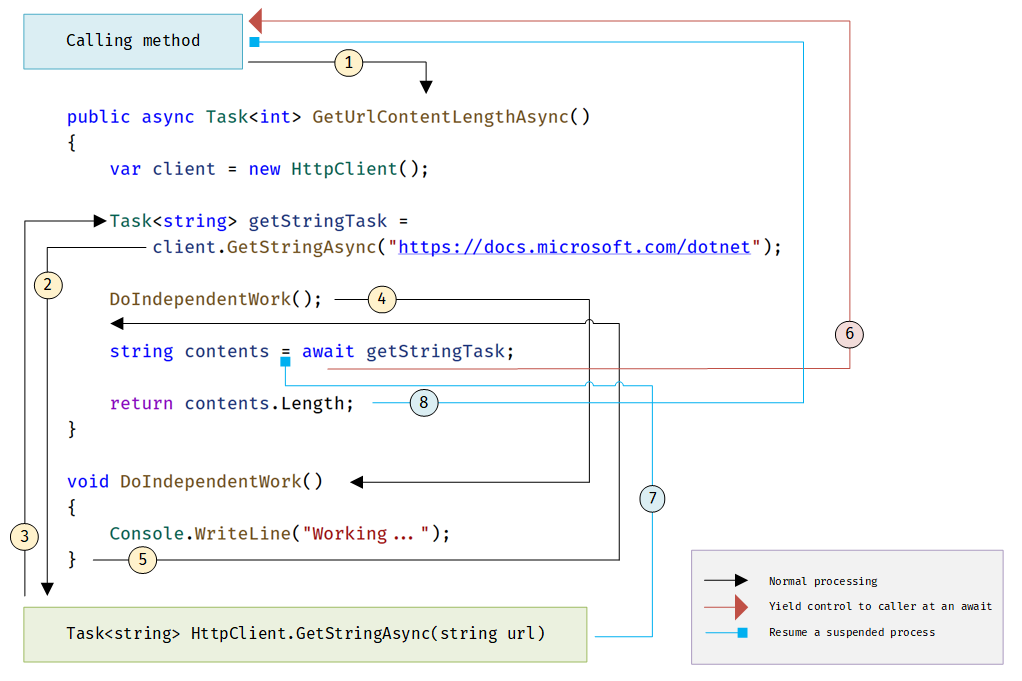

The most important thing to understand in asynchronous programming is how the control flow moves from method to method. The following diagram leads you through the process:

The numbers in the diagram correspond to the following steps, initiated when a calling method calls the async method.

A calling method calls and awaits the

GetUrlContentLengthAsyncasync method.GetUrlContentLengthAsynccreates an HttpClient instance and calls the GetStringAsync asynchronous method to download the contents of a website as a string.Something happens in

GetStringAsyncthat suspends its progress. Perhaps it must wait for a website to download or some other blocking activity. To avoid blocking resources,GetStringAsyncyields control to its caller,GetUrlContentLengthAsync.GetStringAsyncreturns a Task<TResult>, whereTResultis a string, andGetUrlContentLengthAsyncassigns the task to thegetStringTaskvariable. The task represents the ongoing process for the call toGetStringAsync, with a commitment to produce an actual string value when the work is complete.Because

getStringTaskisn't awaited yet,GetUrlContentLengthAsynccan continue with other work that doesn't depend on the final result fromGetStringAsync. That work is represented by a call to the synchronous methodDoIndependentWork.DoIndependentWorkis a synchronous method that does its work and returns to its caller.GetUrlContentLengthAsyncruns out of work that it can do without a result fromgetStringTask.GetUrlContentLengthAsyncnext wants to calculate and return the length of the downloaded string, but the method can't calculate that value until the method has the string.Therefore,

GetUrlContentLengthAsyncuses an await operator to suspend its progress and to yield control to the method that calledGetUrlContentLengthAsync.GetUrlContentLengthAsyncreturns aTask<int>to the caller. The task represents a promise to produce an integer result that's the length of the downloaded string.Note

If

GetStringAsync(and thereforegetStringTask) completes beforeGetUrlContentLengthAsyncawaits it, control remains inGetUrlContentLengthAsync. The expense of suspending and then returning toGetUrlContentLengthAsyncwould be wasted if the called asynchronous processgetStringTaskis complete andGetUrlContentLengthAsyncdoesn't have to wait for the final result.Inside the calling method the processing pattern continues. The caller might do other work that doesn't depend on the result from

GetUrlContentLengthAsyncbefore awaiting that result, or the caller might await immediately. The calling method is waiting forGetUrlContentLengthAsync, andGetUrlContentLengthAsyncis waiting forGetStringAsync.GetStringAsynccompletes and produces a string result. The string result isn't returned by the call toGetStringAsyncin the way that you might expect. (Remember that the method already returned a task in step 3.) Instead, the string result is stored in the task that represents the completion of the method,getStringTask. The await operator retrieves the result fromgetStringTask. The assignment statement assigns the retrieved result tocontents.When

GetUrlContentLengthAsynchas the string result, the method can calculate the length of the string. Then the work ofGetUrlContentLengthAsyncis also complete, and the waiting event handler can resume. In the full example at the end of the article, you can confirm that the event handler retrieves and prints the value of the length result. If you're new to asynchronous programming, take a minute to consider the difference between synchronous and asynchronous behavior. A synchronous method returns when its work is complete (step 5), but an async method returns a task value when its work is suspended (steps 3 and 6). When the async method eventually completes its work, the task is marked as completed and the result, if any, is stored in the task.

API async methods

You might be wondering where to find methods such as GetStringAsync that support async programming. .NET Framework 4.5 or higher and .NET Core contain many members that work with async and await. You can recognize them by the "Async" suffix appended to the member name, and by their return type of Task or Task<TResult>. For example, the System.IO.Stream class contains methods such as CopyToAsync, ReadAsync, and WriteAsync alongside the synchronous methods CopyTo, Read, and Write.

The Windows Runtime also contains many methods that you can use with async and await in Windows apps. For more information, see Threading and async programming for UWP development, and Asynchronous programming (Windows Store apps) and Quickstart: Calling asynchronous APIs in C# or Visual Basic if you use earlier versions of the Windows Runtime.

Threads

Async methods are intended to be non-blocking operations. An await expression in an async method doesn't block the current thread while the awaited task is running. Instead, the expression signs up the rest of the method as a continuation and returns control to the caller of the async method.

The async and await keywords don't cause extra threads to be created. Async methods don't require multithreading because an async method doesn't run on its own thread. The method runs on the current synchronization context and uses time on the thread only when the method is active. You can use Task.Run to move CPU-bound work to a background thread, but a background thread doesn't help with a process that's just waiting for results to become available.

The async-based approach to asynchronous programming is preferable to existing approaches in almost every case. In particular, this approach is better than the BackgroundWorker class for I/O-bound operations because the code is simpler and you don't have to guard against race conditions. In combination with the Task.Run method, async programming is better than BackgroundWorker for CPU-bound operations because async programming separates the coordination details of running your code from the work that Task.Run transfers to the thread pool.

Async and await

If you specify that a method is an async method by using the async modifier, you enable the following two capabilities.

The marked async method can use await to designate suspension points. The

awaitoperator tells the compiler that the async method can't continue past that point until the awaited asynchronous process is complete. In the meantime, control returns to the caller of the async method.The suspension of an async method at an

awaitexpression doesn't constitute an exit from the method, andfinallyblocks don't run.The marked async method can itself be awaited by methods that call it.

An async method typically contains one or more occurrences of an await operator, but the absence of await expressions doesn't cause a compiler error. If an async method doesn't use an await operator to mark a suspension point, the method executes as a synchronous method does, despite the async modifier. The compiler issues a warning for such methods.

async and await are contextual keywords. For more information and examples, see the following articles:

Return types and parameters

An async method typically returns a Task or a Task<TResult>. Inside an async method, an await operator is applied to a task that's returned from a call to another async method.

You specify Task<TResult> as the return type if the method contains a return statement that specifies an operand of type TResult.

You use Task as the return type if the method has no return statement or has a return statement that doesn't return an operand.

You can also specify any other return type, if the type includes a GetAwaiter method. ValueTask<TResult> is an example of such a type. It's available in the System.Threading.Tasks.Extension NuGet package.

The following example shows how you declare and call a method that returns a Task<TResult> or a Task:

async Task<int> GetTaskOfTResultAsync()

{

int hours = 0;

await Task.Delay(0);

return hours;

}

Task<int> returnedTaskTResult = GetTaskOfTResultAsync();

int intResult = await returnedTaskTResult;

// Single line

// int intResult = await GetTaskOfTResultAsync();

async Task GetTaskAsync()

{

await Task.Delay(0);

// No return statement needed

}

Task returnedTask = GetTaskAsync();

await returnedTask;

// Single line

await GetTaskAsync();

Each returned task represents ongoing work. A task encapsulates information about the state of the asynchronous process and, eventually, either the final result from the process or the exception that the process raises if it doesn't succeed.

An async method can also have a void return type. This return type is used primarily to define event handlers, where a void return type is required. Async event handlers often serve as the starting point for async programs.

An async method that has a void return type can't be awaited, and the caller of a void-returning method can't catch any exceptions that the method throws.

An async method can't declare in, ref or out parameters, but the method can call methods that have such parameters. Similarly, an async method can't return a value by reference, although it can call methods with ref return values.

For more information and examples, see Async return types (C#).

Asynchronous APIs in Windows Runtime programming have one of the following return types, which are similar to tasks:

- IAsyncOperation<TResult>, which corresponds to Task<TResult>

- IAsyncAction, which corresponds to Task

- IAsyncActionWithProgress<TProgress>

- IAsyncOperationWithProgress<TResult,TProgress>

Naming convention

By convention, methods that return commonly awaitable types (for example, Task, Task<T>, ValueTask, ValueTask<T>) should have names that end with "Async". Methods that start an asynchronous operation but don't return an awaitable type shouldn't have names that end with "Async", but might start with "Begin", "Start", or some other verb to suggest this method doesn't return or throw the result of the operation.

You can ignore the convention where an event, base class, or interface contract suggests a different name. For example, you shouldn't rename common event handlers, such as OnButtonClick.

Related articles (Visual Studio)

| Title | Description |

|---|---|

| How to make multiple web requests in parallel by using async and await (C#) | Demonstrates how to start several tasks at the same time. |

| Async return types (C#) | Illustrates the types that async methods can return, and explains when each type is appropriate. |

| Cancel tasks with a cancellation token as a signaling mechanism. | Shows how to add the following functionality to your async solution: - Cancel a list of tasks (C#) - Cancel tasks after a period of time (C#) - Process asynchronous task as they complete (C#) |

| Using async for file access (C#) | Lists and demonstrates the benefits of using async and await to access files. |

| Task-based asynchronous pattern (TAP) | Describes an asynchronous pattern. The pattern is based on the Task and Task<TResult> types. |

| Async Videos on Channel 9 | Provides links to various videos about async programming. |