Train and evaluate a time series forecasting model

In this notebook, we build a program to forecast time series data that has seasonal cycles. We use the NYC Property Sales dataset with dates ranging from 2003 to 2015 published by NYC Department of Finance on the NYC Open Data Portal.

Prerequisites

Get a Microsoft Fabric subscription. Or, sign up for a free Microsoft Fabric trial.

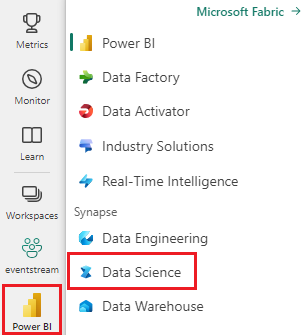

Sign in to Microsoft Fabric.

Use the experience switcher on the bottom left side of your home page to switch to Fabric.

- Familiarity with Microsoft Fabric notebooks.

- A lakehouse to store data for this example. For more information, see Add a lakehouse to your notebook.

Follow along in a notebook

You can follow along in a notebook one of two ways:

- Open and run the built-in notebook.

- Upload your notebook from GitHub.

Open the built-in notebook

The sample Time series notebook accompanies this tutorial.

To open the sample notebook for this tutorial, follow the instructions in Prepare your system for data science tutorials.

Make sure to attach a lakehouse to the notebook before you start running code.

Import the notebook from GitHub

AIsample - Time Series Forecasting.ipynb is the notebook that accompanies this tutorial.

To open the accompanying notebook for this tutorial, follow the instructions in Prepare your system for data science tutorials to import the notebook to your workspace.

If you'd rather copy and paste the code from this page, you can create a new notebook.

Be sure to attach a lakehouse to the notebook before you start running code.

Step 1: Install custom libraries

When you develop a machine learning model, or you handle ad-hoc data analysis, you may need to quickly install a custom library (for example, prophet in this notebook) for the Apache Spark session. To do this, you have two choices.

- You can use the in-line installation capabilities (for example,

%pip,%conda, etc.) to quickly get started with new libraries. This would only install the custom libraries in the current notebook, not in the workspace.

# Use pip to install libraries

%pip install <library name>

# Use conda to install libraries

%conda install <library name>

- Alternatively, you can create a Fabric environment, install libraries from public sources or upload custom libraries to it, and then your workspace admin can attach the environment as the default for the workspace. All the libraries in the environment will then become available for use in any notebooks and Spark job definitions in the workspace. For more information on environments, see create, configure, and use an environment in Microsoft Fabric.

For this notebook, you use %pip install to install the prophet library. The PySpark kernel will restart after %pip install. This means that you must install the library before you run any other cells.

# Use pip to install Prophet

%pip install prophet

Step 2: Load the data

Dataset

This notebook uses the NYC Property Sales data dataset. It covers data from 2003 to 2015, published by the NYC Department of Finance on the NYC Open Data Portal.

The dataset includes a record of every building sale in the New York City property market, within a 13 year period. Refer to the Glossary of Terms for Property Sales Files for a definition of the columns in the dataset.

| borough | neighborhood | building_class_category | tax_class | block | lot | eastment | building_class_at_present | address | apartment_number | zip_code | residential_units | commercial_units | total_units | land_square_feet | gross_square_feet | year_built | tax_class_at_time_of_sale | building_class_at_time_of_sale | sale_price | sale_date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manhattan | ALPHABET CITY | 07 RENTALS - WALKUP APARTMENTS | 0.0 | 384.0 | 17.0 | C4 | 225 EAST 2ND STREET | 10009.0 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 10.0 | 2145.0 | 6670.0 | 1900.0 | 2.0 | C4 | 275000.0 | 2007-06-19 | ||

| Manhattan | ALPHABET CITY | 07 RENTALS - WALKUP APARTMENTS | 2.0 | 405.0 | 12.0 | C7 | 508 EAST 12TH STREET | 10009.0 | 28.0 | 2.0 | 30.0 | 3872.0 | 15428.0 | 1930.0 | 2.0 | C7 | 7794005.0 | 2007-05-21 |

The goal is to build a model that forecasts the monthly total sales, based on historical data. For this, you use Prophet, an open source forecasting library developed by Facebook. Prophet is based on an additive model, where nonlinear trends are fit with daily, weekly, and yearly seasonality, and holiday effects. Prophet works best on time series datasets that have strong seasonal effects, and several seasons of historical data. Additionally, Prophet robustly handles missing data, and data outliers.

Prophet uses a decomposable time series model, consisting of three components:

- trend: Prophet assumes a piece-wise constant rate of growth, with automatic change point selection

- seasonality: By default, Prophet uses Fourier Series to fit weekly and yearly seasonality

- holidays: Prophet requires all past and future occurrences of holidays. If a holiday doesn't repeat in the future, Prophet won't include it in the forecast.

This notebook aggregates the data on a monthly basis, so it ignores the holidays.

Read the official paper for more information about the Prophet modeling techniques.

Download the dataset, and upload to a lakehouse

The data source consists of 15 .csv files. These files contain property sales records from five boroughs in New York, between 2003 and 2015. For convenience, the nyc_property_sales.tar file holds all of these .csv files, compressing them into one file. A publicly available blob storage hosts this .tar file.

Tip

With the parameters shown in this code cell, you can easily apply this notebook to different datasets.

URL = "https://synapseaisolutionsa.blob.core.windows.net/public/NYC_Property_Sales_Dataset/"

TAR_FILE_NAME = "nyc_property_sales.tar"

DATA_FOLDER = "Files/NYC_Property_Sales_Dataset"

TAR_FILE_PATH = f"/lakehouse/default/{DATA_FOLDER}/tar/"

CSV_FILE_PATH = f"/lakehouse/default/{DATA_FOLDER}/csv/"

EXPERIMENT_NAME = "aisample-timeseries" # MLflow experiment name

This code downloads a publicly available version of the dataset, and then stores that dataset in a Fabric Lakehouse.

Important

Make sure you add a lakehouse to the notebook before running it. Failure to do so will result in an error.

import os

if not os.path.exists("/lakehouse/default"):

# Add a lakehouse if the notebook has no default lakehouse

# A new notebook will not link to any lakehouse by default

raise FileNotFoundError(

"Default lakehouse not found, please add a lakehouse for the notebook."

)

else:

# Verify whether or not the required files are already in the lakehouse, and if not, download and unzip

if not os.path.exists(f"{TAR_FILE_PATH}{TAR_FILE_NAME}"):

os.makedirs(TAR_FILE_PATH, exist_ok=True)

os.system(f"wget {URL}{TAR_FILE_NAME} -O {TAR_FILE_PATH}{TAR_FILE_NAME}")

os.makedirs(CSV_FILE_PATH, exist_ok=True)

os.system(f"tar -zxvf {TAR_FILE_PATH}{TAR_FILE_NAME} -C {CSV_FILE_PATH}")

Start recording the run-time of this notebook.

# Record the notebook running time

import time

ts = time.time()

Set up the MLflow experiment tracking

To extend the MLflow logging capabilities, autologging automatically captures the values of input parameters and output metrics of a machine learning model during its training. This information is then logged to the workspace, where the MLflow APIs or the corresponding experiment in the workspace can access and visualize it. Visit this resource for more information about autologging.

# Set up the MLflow experiment

import mlflow

mlflow.set_experiment(EXPERIMENT_NAME)

mlflow.autolog(disable=True) # Disable MLflow autologging

Note

If you want to disable Microsoft Fabric autologging in a notebook session, call mlflow.autolog() and set disable=True.

Read raw date data from the lakehouse

df = (

spark.read.format("csv")

.option("header", "true")

.load("Files/NYC_Property_Sales_Dataset/csv")

)

Step 3: Begin exploratory data analysis

To review the dataset, you could manually examine a subset of data to gain a better understanding of it. You can use the display function to print the DataFrame. You can also show the Chart views, to easily visualize subsets of the dataset.

display(df)

A manual review of the dataset leads to some early observations:

Instances of $0.00 sales prices. According to the Glossary of Terms, this implies a transfer of ownership with no cash consideration. In other words, no cash flowed in the transaction. You should remove sales with $0.00

sales_pricevalues from the dataset.The dataset covers different building classes. However, this notebook will focus on residential buildings which, according to the Glossary of Terms, are marked as type "A". You should filter the dataset to include only residential buildings. To do this, include either the

building_class_at_time_of_saleor thebuilding_class_at_presentcolumns. You must only include thebuilding_class_at_time_of_saledata.The dataset includes instances where

total_unitsvalues equal 0, orgross_square_feetvalues equal 0. You should remove all the instances wheretotal_unitsorgross_square_unitsvalues equal 0.Some columns - for example,

apartment_number,tax_class,build_class_at_present, etc. - have missing or NULL values. Assume that the missing data involves clerical errors, or nonexistent data. The analysis doesn't depend on these missing values, so you can ignore them.The

sale_pricecolumn is stored as a string, with a prepended "$" character. To proceed with the analysis, represent this column as a number. You should cast thesale_pricecolumn as integer.

Type conversion and filtering

To resolve some of the identified issues, import the required libraries.

# Import libraries

import pyspark.sql.functions as F

from pyspark.sql.types import *

Cast the sales data from string to integer

Use regular expressions to separate the numeric portion of the string from the dollar sign (for example, in the string $300,000, split $ and 300,000), and then cast the numeric portion as an integer.

Next, filter the data to only include instances that meet all of these conditions:

- The

sales_priceis greater than 0 - The

total_unitsis greater than 0 - The

gross_square_feetis greater than 0 - The

building_class_at_time_of_saleis of type A

df = df.withColumn(

"sale_price", F.regexp_replace("sale_price", "[$,]", "").cast(IntegerType())

)

df = df.select("*").where(

'sale_price > 0 and total_units > 0 and gross_square_feet > 0 and building_class_at_time_of_sale like "A%"'

)

Aggregation on monthly basis

The data resource tracks property sales on a daily basis, but this approach is too granular for this notebook. Instead, aggregate the data on a monthly basis.

First, change the date values to show only month and year data. The date values would still include the year data. You could still distinguish between, for example, December 2005 and December 2006.

Additionally, only keep the columns relevant to the analysis. These include sales_price, total_units, gross_square_feet and sales_date. You must also rename sales_date to month.

monthly_sale_df = df.select(

"sale_price",

"total_units",

"gross_square_feet",

F.date_format("sale_date", "yyyy-MM").alias("month"),

)

display(monthly_sale_df)

Aggregate the sale_price, total_units and gross_square_feet values by month. Then, group the data by month, and sum all the values within each group.

summary_df = (

monthly_sale_df.groupBy("month")

.agg(

F.sum("sale_price").alias("total_sales"),

F.sum("total_units").alias("units"),

F.sum("gross_square_feet").alias("square_feet"),

)

.orderBy("month")

)

display(summary_df)

Pyspark to Pandas conversion

Pyspark DataFrames handle large datasets well. However, due to data aggregation, the DataFrame size is smaller. This suggests that you can now use pandas DataFrames.

This code casts the dataset from a pyspark DataFrame to a pandas DataFrame.

import pandas as pd

df_pandas = summary_df.toPandas()

display(df_pandas)

Visualization

You can examine the property trade trend of New York City to better understand the data. This leads to insights into potential patterns and seasonality trends. Learn more about Microsoft Fabric data visualization at this resource.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

import numpy as np

f, (ax1, ax2) = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(35, 10))

plt.sca(ax1)

plt.xticks(np.arange(0, 15 * 12, step=12))

plt.ticklabel_format(style="plain", axis="y")

sns.lineplot(x="month", y="total_sales", data=df_pandas)

plt.ylabel("Total Sales")

plt.xlabel("Time")

plt.title("Total Property Sales by Month")

plt.sca(ax2)

plt.xticks(np.arange(0, 15 * 12, step=12))

plt.ticklabel_format(style="plain", axis="y")

sns.lineplot(x="month", y="square_feet", data=df_pandas)

plt.ylabel("Total Square Feet")

plt.xlabel("Time")

plt.title("Total Property Square Feet Sold by Month")

plt.show()

Summary of observations from the exploratory data analysis

- The data shows a clear recurring pattern on a yearly cadence; this means the data has a yearly seasonality

- The summer months seem to have higher sales volumes compared to winter months

- In a comparison of years with high sales and years with low sales, the revenue difference between high sales months and low sales months in high sales years exceeds - in absolute terms - the revenue difference between high sales months and low sales months in low sale years.

For example, in 2004, the revenue difference between the highest sales month and the lowest sales month is about:

$900,000,000 - $500,000,000 = $400,000,000

For 2011, that revenue difference calculation is about:

$400,000,000 - $300,000,000 = $100,000,000

This becomes important later, when you must decide between multiplicative and additive seasonality effects.

Step 4: Model training and tracking

Model fitting

Prophet input is always a two-column DataFrame. One input column is a time column named ds, and one input column is a value column named y. The time column should have a date, time, or datetime data format (for example, YYYY_MM). The dataset here meets that condition. The value column must be a numerical data format.

For the model fitting, you must only rename the time column to ds and value column to y, and pass the data to Prophet. Read the Prophet Python API documentation for more information.

df_pandas["ds"] = pd.to_datetime(df_pandas["month"])

df_pandas["y"] = df_pandas["total_sales"]

Prophet follows the scikit-learn convention. First, create a new instance of Prophet, set certain parameters (for example,seasonality_mode), and then fit that instance to the dataset.

Although a constant additive factor is the default seasonality effect for Prophet, you should use the 'multiplicative' seasonality for the seasonality effect parameter. The analysis in the previous section showed that because of changes in seasonality amplitude, a simple additive seasonality won't fit the data well at all.

Set the weekly_seasonality parameter to off, because the data was aggregated by month. As a result, weekly data isn't available.

Use Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods to capture the seasonality uncertainty estimates. By default, Prophet can provide uncertainty estimates on the trend and observation noise, but not for the seasonality. MCMC require more processing time, but they allow the algorithm to provide uncertainty estimates on the seasonality, and the trend and observation noise. Read the Prophet Uncertainty Intervals documentation for more information.

Tune the automatic change point detection sensitivity through the changepoint_prior_scale parameter. The Prophet algorithm automatically tries to find instances in the data where the trajectories abruptly change. It can become difficult to find the correct value. To resolve this, you can try different values and then select the model with the best performance. Read the Prophet Trend Changepoints documentation for more information.

from prophet import Prophet

def fit_model(dataframe, seasonality_mode, weekly_seasonality, chpt_prior, mcmc_samples):

m = Prophet(

seasonality_mode=seasonality_mode,

weekly_seasonality=weekly_seasonality,

changepoint_prior_scale=chpt_prior,

mcmc_samples=mcmc_samples,

)

m.fit(dataframe)

return m

Cross validation

Prophet has a built-in cross-validation tool. This tool can estimate the forecasting error, and find the model with the best performance.

The cross-validation technique can validate model efficiency. This technique trains the model on a subset of the dataset, and runs tests on a previously-unseen subset of the dataset. This technique can check how well a statistical model generalizes to an independent dataset.

For cross-validation, reserve a particular sample of the dataset, which wasn't part of the training dataset. Then, test the trained model on that sample, prior to deployment. However, this approach doesn't work for time-series data, because if the model has seen data from the months of January 2005 and March 2005, and you try to predict for the month February 2005, the model can essentially cheat, because it could see where the data trend leads. In real applications, the aim is to forecast for the future, as the unseen regions.

To handle this, and make the test reliable, split the dataset based on the dates. Use the dataset up to a certain date (for example, the first 11 years of data) for training, and then use the remaining unseen data for prediction.

In this scenario, start with 11 years of training data, and then make monthly predictions using a one-year horizon. Specifically, the training data contains everything from 2003 through 2013. Then, the first run handles predictions for January 2014 through January 2015. The next run handles predictions for February 2014 through February 2015, and so on.

Repeat this process for each of the three trained models, to see which model performs the best. Then, compare these predictions with real-world values, to establish the prediction quality of the best model.

from prophet.diagnostics import cross_validation

from prophet.diagnostics import performance_metrics

def evaluation(m):

df_cv = cross_validation(m, initial="4017 days", period="30 days", horizon="365 days")

df_p = performance_metrics(df_cv, monthly=True)

future = m.make_future_dataframe(periods=12, freq="M")

forecast = m.predict(future)

return df_p, future, forecast

Log model with MLflow

Log the models, to keep track of their parameters, and save the models for later use. All relevant model information is logged in the workspace, under the experiment name. The model, parameters, and metrics, along with MLflow autologging items, is saved in one MLflow run.

# Setup MLflow

from mlflow.models.signature import infer_signature

Conduct experiments

A machine learning experiment serves as the primary unit of organization and control, for all related machine learning runs. A run corresponds to a single execution of model code. Machine learning experiment tracking refers to the management of all the different experiments and their components. This includes parameters, metrics, models and other artifacts, and it helps organize the required components of a specific machine learning experiment. Machine learning experiment tracking also allows for the easy duplication of past results with saved experiments. Learn more about machine learning experiments in Microsoft Fabric. Once you determine the steps you intend to include (for example, fitting and evaluating the Prophet model in this notebook), you can run the experiment.

model_name = f"{EXPERIMENT_NAME}-prophet"

models = []

df_metrics = []

forecasts = []

seasonality_mode = "multiplicative"

weekly_seasonality = False

changepoint_priors = [0.01, 0.05, 0.1]

mcmc_samples = 100

for chpt_prior in changepoint_priors:

with mlflow.start_run(run_name=f"prophet_changepoint_{chpt_prior}"):

# init model and fit

m = fit_model(df_pandas, seasonality_mode, weekly_seasonality, chpt_prior, mcmc_samples)

models.append(m)

# Validation

df_p, future, forecast = evaluation(m)

df_metrics.append(df_p)

forecasts.append(forecast)

# Log model and parameters with MLflow

mlflow.prophet.log_model(

m,

model_name,

registered_model_name=model_name,

signature=infer_signature(future, forecast),

)

mlflow.log_params(

{

"seasonality_mode": seasonality_mode,

"mcmc_samples": mcmc_samples,

"weekly_seasonality": weekly_seasonality,

"changepoint_prior": chpt_prior,

}

)

metrics = df_p.mean().to_dict()

metrics.pop("horizon")

mlflow.log_metrics(metrics)

Visualize a model with Prophet

Prophet has built-in visualization functions, which can show the model fitting results.

The black dots denote the data points that are used to train the model. The blue line is the prediction, and the light blue area shows the uncertainty intervals. You have built three models with different changepoint_prior_scale values. The predictions of these three models are shown in the results of this code block.

for idx, pack in enumerate(zip(models, forecasts)):

m, forecast = pack

fig = m.plot(forecast)

fig.suptitle(f"changepoint = {changepoint_priors[idx]}")

The smallest changepoint_prior_scale value in the first graph leads to an underfitting of trend changes. The largest changepoint_prior_scale in the third graph could result in overfitting. So, the second graph seems to be the optimal choice. This implies that the second model is the most suitable.

Visualize trends and seasonality with Prophet

Prophet can also easily visualize the underlying trends and seasonalities. Visualizations of the second model are shown in the results of this code block.

BEST_MODEL_INDEX = 1 # Set the best model index according to the previous results

fig2 = models[BEST_MODEL_INDEX].plot_components(forecast)

In these graphs, the light blue shading reflects the uncertainty. The top graph shows a strong, long-period oscillating trend. Over a few years, the sales volumes rise and fall. The lower graph shows that sales tend to peak in February and September, reaching their maximum values for the year in those months. Shortly after those months, in March and October, they fall to the year's minimum values.

Evaluate the performance of the models using various metrics, for example:

- mean squared error (MSE)

- root mean squared error (RMSE)

- mean absolute error (MAE)

- mean absolute percent error (MAPE)

- median absolute percent error (MDAPE)

- symmetric mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE)

Evaluate the coverage using the yhat_lower and yhat_upper estimates. Note the varying horizons where you predict one year in the future, 12 times.

display(df_metrics[BEST_MODEL_INDEX])

With the MAPE metric, for this forecasting model, predictions that extend one month into the future typically involve errors of roughly 8%. However, for predictions one year into the future, the error increases to roughly 10%.

Step 5: Score the model and save prediction results

Now score the model, and save the prediction results.

Make predictions with Predict Transformer

Now, you can load the model and use it to make predictions. Users can operationalize machine learning models with PREDICT, a scalable Microsoft Fabric function that supports batch scoring in any compute engine. Learn more about PREDICT, and how to use it within Microsoft Fabric, at this resource.

from synapse.ml.predict import MLFlowTransformer

spark.conf.set("spark.synapse.ml.predict.enabled", "true")

model = MLFlowTransformer(

inputCols=future.columns.values,

outputCol="prediction",

modelName=f"{EXPERIMENT_NAME}-prophet",

modelVersion=BEST_MODEL_INDEX,

)

test_spark = spark.createDataFrame(data=future, schema=future.columns.to_list())

batch_predictions = model.transform(test_spark)

display(batch_predictions)

# Code for saving predictions into lakehouse

batch_predictions.write.format("delta").mode("overwrite").save(

f"{DATA_FOLDER}/predictions/batch_predictions"

)

# Determine the entire runtime

print(f"Full run cost {int(time.time() - ts)} seconds.")