Notitie

Voor toegang tot deze pagina is autorisatie vereist. U kunt proberen u aan te melden of de directory te wijzigen.

Voor toegang tot deze pagina is autorisatie vereist. U kunt proberen de mappen te wijzigen.

In dit artikel wordt de Windows Hello-technologie beschreven die wordt geleverd als onderdeel van Windows en wordt besproken hoe ontwikkelaars deze technologie kunnen implementeren om hun Windows-apps en back-endservices te beveiligen. Het benadrukt specifieke mogelijkheden van deze technologieën die helpen bij het beperken van bedreigingen die ontstaan door het gebruik van conventionele inloggegevens en biedt richtlijnen over het ontwerpen en implementeren van deze technologieën als onderdeel van de uitrol van een Windows-client.

Opmerking

Dit artikel is gericht op app-ontwikkeling. Voor informatie over de architectuur en implementatiedetails van Windows Hello, zie Plan een Windows Hello voor Bedrijven-implementatie.

nl-NL: Voor een stapsgewijze handleiding over het maken van een WinUI-app met Windows Hello en de authenticatie-service, zie de Windows Hello-aanmeldingsapp en Windows Hello-aanmeldingsservice artikelen.

Introductie

Een fundamentele aanname over informatiebeveiliging is dat een systeem kan identificeren wie het gebruikt. Door een gebruiker te identificeren, kan het systeem bepalen of de gebruiker op de juiste wijze wordt geïdentificeerd (een proces dat bekend staat als verificatie) en vervolgens bepalen wat een correct geverifieerde gebruiker moet kunnen doen (autorisatie). Het overgrote deel van de computersystemen die overal ter wereld worden geïmplementeerd, is afhankelijk van gebruikersreferenties voor het nemen van verificatie- en autorisatiebeslissingen. Dit betekent dat deze systemen afhankelijk zijn van herbruikbare, door de gebruiker gemaakte wachtwoorden als basis voor hun beveiliging. De vaak aangehaalde maxim dat authenticatie kan betekenen "iets dat je weet, iets dat je hebt, of iets dat je bent" maakt het probleem duidelijk: een herbruikbaar wachtwoord is op zichzelf een authenticatiefactor, zodat iedereen die het wachtwoord kent, de gebruiker kan nabootsen die het bezit.

Problemen met traditionele referenties

Sinds de jaren '60, toen Fernando Corbató en zijn team aan het Massachusetts Institute of Technology de introductie van het wachtwoord voorstonden, moesten gebruikers en beheerders omgaan met het gebruik van wachtwoorden voor gebruikersverificatie en autorisatie. In de loop van de tijd is de state-of-the-art voor wachtwoordopslag en -gebruik enigszins geavanceerd (met bijvoorbeeld veilige hashing en salting), maar we worden nog steeds geconfronteerd met twee problemen. Wachtwoorden zijn eenvoudig te klonen en ze zijn gemakkelijk te stelen. Bovendien kunnen implementatiefouten onveilig maken en hebben gebruikers een moeilijke balans tussen gemak en beveiliging.

Referentiediefstal

Het grootste risico van wachtwoorden is eenvoudig: een aanvaller kan ze gemakkelijk stelen. Elke plaats waar een wachtwoord wordt ingevoerd, verwerkt of opgeslagen, is kwetsbaar. Een aanvaller kan bijvoorbeeld een verzameling wachtwoorden of hashes van een verificatieserver stelen door afluisteren van netwerkverkeer naar een toepassingsserver, door malware in een toepassing of op een apparaat te implanteren, door gebruikerstoetsaanslagen op een apparaat te registreren of door te kijken welke tekens een gebruiker typt. Dit zijn alleen de meest voorkomende aanvalsmethoden.

Een ander gerelateerd risico is dat referenties opnieuw worden afgespeeld, waarbij een aanvaller een geldige referentie vastlegt door afluisteren op een onveilig netwerk en deze later opnieuw afspeelt om een geldige gebruiker te imiteren. De meeste verificatieprotocollen (inclusief Kerberos en OAuth) beschermen tegen herhalingsaanvallen door een tijdstempel op te geven in het proces voor het uitwisselen van referenties, maar die tactiek beschermt alleen het token dat door het verificatiesysteem wordt opgegeven, niet het wachtwoord dat de gebruiker biedt om het ticket op te halen.

Inloggegevens opnieuw gebruiken

De algemene benadering van het gebruik van een e-mailadres als gebruikersnaam maakt een slecht probleem erger. Een aanvaller die een gebruikersnaam-wachtwoordpaar herstelt van een gecompromitteerd systeem, kan datzelfde paar vervolgens proberen op andere systemen. Deze tactiek werkt verrassend vaak om aanvallers in staat te stellen van een gecompromitteerd systeem naar andere systemen te springen. Het gebruik van e-mailadressen als gebruikersnamen leidt tot extra problemen die verderop in deze handleiding worden besproken.

Problemen met referenties oplossen

Het oplossen van de problemen die wachtwoorden vormen, is lastig. Alleen het verscherpen van wachtwoordbeleid zal dit niet doen; gebruikers kunnen wachtwoorden alleen recyclen, delen of opschrijven. Hoewel gebruikersonderwijs essentieel is voor verificatiebeveiliging, wordt het probleem ook niet opgelost in het onderwijs.

Windows Hello vervangt wachtwoorden door sterke tweeledige verificatie (2FA) door bestaande referenties te verifiëren en door een apparaatspecifieke referentie te maken die een biometrische of op pincode gebaseerde gebruikersbeweging beschermt.

Wat is Windows Hello?

Windows Hello is een biometrisch aanmeldingssysteem dat is ingebouwd in Windows waarmee u uw gezicht, vingerafdruk of pincode kunt gebruiken om uw apparaat te ontgrendelen. Het vervangt traditionele wachtwoorden door een veiligere en handigere methode. Uw biometrische gegevens worden veilig opgeslagen op uw apparaat en zelfs als iemand uw apparaat steelt, heeft deze geen toegang zonder uw pincode of biometrische gebaar. Zodra deze zijn ontgrendeld, hebt u naadloos toegang tot uw apps, gegevens en services.

De Windows Hello-verificator wordt een Hello genoemd. Elke Hello is uniek voor een specifieke gebruiker en een specifiek apparaat. Het synchroniseert niet tussen apparaten of deelt gegevens met servers of apps. Als meerdere personen hetzelfde apparaat gebruiken, moet elke persoon een eigen Windows Hello-configuratie instellen. Deze configuratie is gekoppeld aan hun referenties op dat specifieke apparaat. U kunt een Hello beschouwen als een sleutel waarmee uw opgeslagen referenties worden ontgrendeld, die vervolgens worden gebruikt om u aan te melden bij apps of services. Het is geen referentie zelf, maar fungeert als een tweede beveiligingslaag tijdens verificatie.

Windows Hello-verificatie

Windows Hello biedt een robuuste manier voor een apparaat om een afzonderlijke gebruiker te herkennen, die het eerste deel van het pad tussen een gebruiker en een aangevraagd service- of gegevensitem aanpakt. Nadat het apparaat de gebruiker heeft herkend, moet de gebruiker nog steeds worden geverifieerd voordat wordt bepaald of er toegang moet worden verleend tot een aangevraagde resource. Windows Hello biedt een sterke 2FA die volledig is geïntegreerd in Windows en herbruikbare wachtwoorden vervangt door de combinatie van een specifiek apparaat en een biometrische beweging of pincode.

Windows Hello is echter niet alleen een vervanging voor traditionele 2FA-systemen. Het is conceptueel vergelijkbaar met smartcards: verificatie wordt uitgevoerd met behulp van cryptografische primitieven in plaats van tekenreeksvergelijkingen en het sleutelmateriaal van de gebruiker is veilig binnen manipulatiebestendige hardware. Windows Hello vereist ook niet de extra infrastructuuronderdelen die nodig zijn voor smartcardimplementatie. U hebt met name geen PKI (Public Key Infrastructure) nodig om certificaten te beheren, als u er momenteel nog geen hebt. Windows Hello combineert de belangrijkste voordelen van smartcards, implementatieflexibiliteit voor virtuele smartcards en robuuste beveiliging voor fysieke smartcards, zonder hun nadelen.

Hoe Windows Hello werkt

Wanneer de gebruiker Windows Hello op zijn computer instelt, wordt er een nieuw openbaar persoonlijk sleutelpaar op het apparaat gegenereerd. De trusted platform module (TPM) genereert en beveiligt deze persoonlijke sleutel. Als het apparaat geen TPM-chip heeft, wordt de persoonlijke sleutel versleuteld en beveiligd door software. Daarnaast genereren TPM-apparaten een gegevensblok dat kan worden gebruikt om te bevestigen dat een sleutel is gebonden aan TPM. Deze attestation-informatie kan worden gebruikt in uw oplossing om te bepalen of de gebruiker bijvoorbeeld een ander autorisatieniveau krijgt.

Als u Windows Hello wilt inschakelen op een apparaat, moet de gebruiker zijn of haar Microsoft Entra ID-account of Microsoft-account hebben verbonden in windows-instellingen.

Hoe sleutels worden beveiligd

Telkens wanneer sleutelmateriaal wordt gegenereerd, moet het worden beschermd tegen aanvallen. De meest robuuste manier om dit te doen is via gespecialiseerde hardware. Er is een lange geschiedenis van het gebruik van HSM's (Hardware Security Modules) voor het genereren, opslaan en verwerken van sleutels voor beveiligingskritieke toepassingen. Smartcards zijn een speciaal type HSM, net als apparaten die voldoen aan de TPM-standaard van de Trusted Computing Group. Waar mogelijk maakt de implementatie van Windows Hello gebruik van TPM-hardware aan boord om sleutels te genereren, op te slaan en te verwerken. Voor Windows Hello en Windows Hello for Work is echter geen onboard-TPM vereist.

Waar mogelijk raadt Microsoft het gebruik van TPM-hardware aan. De TPM beschermt tegen verschillende bekende en potentiële aanvallen, waaronder beveiligingsaanvallen op pincodes. De TPM biedt ook een extra beveiligingslaag na een accountvergrendeling. Wanneer de TPM het sleutelmateriaal heeft vergrendeld, moet de gebruiker de pincode opnieuw instellen. Het opnieuw instellen van de pincode betekent dat alle sleutels en certificaten die zijn versleuteld met het oude sleutelmateriaal worden verwijderd.

Authenticatie

Wanneer een gebruiker toegang wil krijgen tot beveiligd sleutelmateriaal, begint het verificatieproces met de gebruiker die een pincode of biometrische beweging invoert om het apparaat te ontgrendelen, een proces dat ook wel 'de sleutel vrijgeven' wordt genoemd.

Een toepassing kan de sleutels van een andere toepassing nooit gebruiken, noch kan iemand de sleutels van een andere gebruiker gebruiken. Deze sleutels worden gebruikt om aanvragen te ondertekenen die worden verzonden naar de id-provider of IDP, op zoek naar toegang tot opgegeven resources. Toepassingen kunnen specifieke API's gebruiken om bewerkingen aan te vragen waarvoor sleutelmateriaal voor bepaalde acties is vereist. Toegang via deze API's vereist expliciete validatie via een gebruikersbeweging en het sleutelmateriaal wordt niet blootgesteld aan de aanvragende toepassing. In plaats daarvan vraagt de toepassing om een specifieke actie, zoals het ondertekenen van een stukje gegevens, en de Windows Hello-laag verwerkt het werkelijke werk en retourneert de resultaten.

Voorbereiden om Windows Hello te implementeren

Nu we een basiskennis hebben van hoe Windows Hello werkt, gaan we kijken hoe ze in onze eigen toepassingen kunnen worden geïmplementeerd.

Er zijn verschillende scenario's die we kunnen implementeren met Behulp van Windows Hello. U hoeft zich bijvoorbeeld alleen maar aan te melden bij uw app op een apparaat. Het andere veelvoorkomende scenario is verificatie bij een service. In plaats van een aanmeldingsnaam en wachtwoord te gebruiken, gebruikt u Windows Hello. In de volgende secties bespreken we het implementeren van een aantal verschillende scenario's, waaronder het verifiëren van uw services met Windows Hello en het converteren van een bestaand gebruikersnaam-/wachtwoordsysteem naar een Windows Hello-systeem.

Windows Hello implementeren

In deze sectie beginnen we met een greenfield-scenario zonder bestaand verificatiesysteem en leggen we uit hoe u Windows Hello implementeert.

In de volgende sectie wordt beschreven hoe u migreert van een bestaand gebruikersnaam-/wachtwoordsysteem. Maar zelfs als die sectie u meer interesseert, kunt u deze bekijken om een basiskennis van het proces en de vereiste code te krijgen.

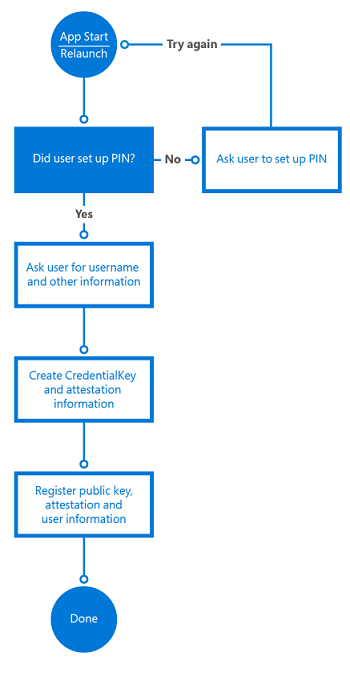

Nieuwe gebruikers inschrijven

We beginnen met een gloednieuwe service die Gebruikmaakt van Windows Hello en een hypothetische nieuwe gebruiker die klaar is om zich aan te melden op een nieuw apparaat.

De eerste stap is om te controleren of de gebruiker Windows Hello kan gebruiken. De app controleert de gebruikersinstellingen en computermogelijkheden om ervoor te zorgen dat deze gebruikers-id-sleutels kan maken. Als de app bepaalt dat de gebruiker Windows Hello nog niet heeft ingeschakeld, wordt de gebruiker gevraagd dit in te stellen voordat de app wordt gebruikt.

Als u Windows Hello wilt inschakelen, hoeft de gebruiker alleen een pincode in te stellen in Windows-instellingen, tenzij de gebruiker deze heeft ingesteld tijdens de Out of Box Experience (OOBE).

In de volgende regels code ziet u een eenvoudige manier om te controleren of de gebruiker is ingesteld voor Windows Hello.

var keyCredentialAvailable = await KeyCredentialManager.IsSupportedAsync();

if (!keyCredentialAvailable)

{

// User didn't set up PIN yet

return;

}

De volgende stap bestaat uit het vragen van de gebruiker om informatie om zich aan te melden bij uw service. U kunt ervoor kiezen om de gebruiker te vragen om voornaam, achternaam, e-mailadres en een unieke gebruikersnaam. U kunt het e-mailadres gebruiken als de unieke id; Het is aan jou.

In dit scenario gebruiken we het e-mailadres als de unieke id voor de gebruiker. Zodra de gebruiker zich heeft geregistreerd, kunt u overwegen een validatie-e-mail te verzenden om ervoor te zorgen dat het adres geldig is. Dit biedt u een mechanisme om het account zo nodig opnieuw in te stellen.

Als de gebruiker zijn of haar pincode heeft ingesteld, maakt de app de KeyCredential van de gebruiker. De app haalt ook de optionele sleutelverklaringsgegevens op om cryptografisch bewijs te verkrijgen dat de sleutel wordt gegenereerd op de TPM. De gegenereerde openbare sleutel en eventueel de attestation worden verzonden naar de back-endserver om het gebruikte apparaat te registreren. Elk sleutelpaar dat op elk apparaat wordt gegenereerd, is uniek.

De code voor het maken van keyCredential ziet er als volgt uit:

var keyCreationResult = await KeyCredentialManager.RequestCreateAsync(

AccountId, KeyCredentialCreationOption.ReplaceExisting);

RequestCreateAsync is de aanroep waarmee de openbare en persoonlijke sleutel wordt gemaakt. Als het apparaat de juiste TPM-chip heeft, vragen de API's de TPM-chip om de persoonlijke en openbare sleutel te maken en het resultaat op te slaan; als er geen TPM-chip beschikbaar is, maakt het besturingssysteem het sleutelpaar in code. De app heeft geen rechtstreekse toegang tot de gemaakte persoonlijke sleutels. Een deel van het maken van de sleutelparen is ook de resulterende attestatie-informatie. (Zie de volgende sectie voor meer informatie over attestation.)

Nadat het sleutelpaar en de attestation-informatie op het apparaat zijn gemaakt, moeten de openbare sleutel, de optionele attestation-informatie en de unieke id (zoals het e-mailadres) worden verzonden naar de back-endregistratieservice en worden opgeslagen in de back-end.

Om de gebruiker toegang te geven tot de app op meerdere apparaten, moet de back-endservice meerdere sleutels voor dezelfde gebruiker kunnen opslaan. Omdat elke sleutel uniek is voor elk apparaat, slaan we al deze sleutels op die zijn verbonden met dezelfde gebruiker. Een apparaat-id wordt gebruikt om het serveronderdeel te optimaliseren bij het verifiëren van gebruikers. In de volgende sectie bespreken we dit in meer detail.

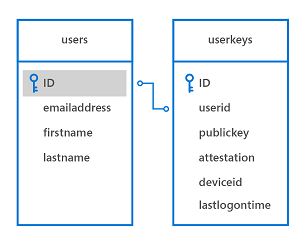

Een voorbeelddatabaseschema voor het opslaan van deze informatie in de back-end kan er als volgt uitzien:

De registratielogica kan er als volgt uitzien:

De registratiegegevens die u verzamelt, kunnen natuurlijk veel meer identificatiegegevens bevatten dan we in dit eenvoudige scenario opnemen. Als uw app bijvoorbeeld toegang heeft tot een beveiligde service, zoals een voor het bankwezen, moet u een bewijs van identiteit en andere zaken aanvragen als onderdeel van het registratieproces. Zodra aan alle voorwaarden is voldaan, wordt de openbare sleutel van deze gebruiker opgeslagen in de back-end en gebruikt om te valideren wanneer de gebruiker de service de volgende keer gebruikt.

using System;

using System.Runtime;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Windows.Storage.Streams;

using Windows.Security.Credentials;

static async void RegisterUser(string AccountId)

{

var keyCredentialAvailable = await KeyCredentialManager.IsSupportedAsync();

if (!keyCredentialAvailable)

{

// The user didn't set up a PIN yet

return;

}

var keyCreationResult = await KeyCredentialManager.RequestCreateAsync(AccountId, KeyCredentialCreationOption.ReplaceExisting);

if (keyCreationResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.Success)

{

var userKey = keyCreationResult.Credential;

var publicKey = userKey.RetrievePublicKey();

var keyAttestationResult = await userKey.GetAttestationAsync();

IBuffer keyAttestation = null;

IBuffer certificateChain = null;

bool keyAttestationIncluded = false;

bool keyAttestationCanBeRetrievedLater = false;

keyAttestationResult = await userKey.GetAttestationAsync();

KeyCredentialAttestationStatus keyAttestationRetryType = 0;

switch (keyAttestationResult.Status)

{

case KeyCredentialAttestationStatus.Success:

keyAttestationIncluded = true;

keyAttestation = keyAttestationResult.AttestationBuffer;

certificateChain = keyAttestationResult.CertificateChainBuffer;

break;

case KeyCredentialAttestationStatus.TemporaryFailure:

keyAttestationRetryType = KeyCredentialAttestationStatus.TemporaryFailure;

keyAttestationCanBeRetrievedLater = true;

break;

case KeyCredentialAttestationStatus.NotSupported:

keyAttestationRetryType = KeyCredentialAttestationStatus.NotSupported;

keyAttestationCanBeRetrievedLater = true;

break;

}

}

else if (keyCreationResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.UserCanceled ||

keyCreationResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.UserPrefersPassword)

{

// Show error message to the user to get confirmation that user

// does not want to enroll.

}

}

Verklaring

Bij het maken van het sleutelpaar is er ook een optie om de attestation-informatie aan te vragen, die wordt gegenereerd door de TPM-chip. Deze optionele informatie kan worden verzonden naar de server als onderdeel van het registratieproces. TPM-sleutelverklaring is een protocol dat cryptografisch bewijst dat een sleutel TPM-gebonden is. Dit type attestation kan worden gebruikt om te garanderen dat een bepaalde cryptografische bewerking heeft plaatsgevonden in de TPM van een bepaalde computer.

Wanneer de gegenereerde RSA-sleutel, de attestation-instructie en het AIK-certificaat worden ontvangen, controleert de server de volgende voorwaarden:

- De handtekening van het AIK-certificaat is geldig.

- Het AIK-certificaat is gekoppeld aan een vertrouwde basis.

- Het AIK-certificaat en de bijbehorende keten zijn ingeschakeld voor EKU OID "2.23.133.8.3" (beschrijvende naam is 'Attestation Identity Key Certificate').

- Het AIK-certificaat is geldig.

- Alle verlenende CA-certificaten in de keten zijn tijd geldig en worden niet ingetrokken.

- De attestatieverklaring wordt correct gevormd.

- De handtekening op KeyAttestation-blob maakt gebruik van een openbare AIK-sleutel.

- De openbare sleutel die is opgenomen in de KeyAttestation-blob komt overeen met de openbare RSA-sleutel die de client heeft verzonden naast de attestation-instructie.

Uw app kan de gebruiker een ander autorisatieniveau toewijzen, afhankelijk van deze voorwaarden. Als een van deze controles bijvoorbeeld mislukt, kan het de gebruiker niet inschrijven of beperken wat de gebruiker kan doen.

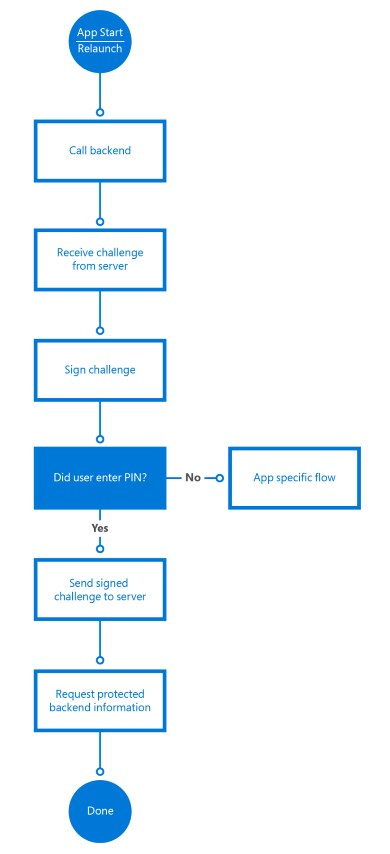

Aanmelden met Windows Hello

Zodra de gebruiker is ingeschreven bij uw systeem, kan hij of zij de app gebruiken. Afhankelijk van het scenario kunt u gebruikers vragen om zich te verifiëren voordat ze de app kunnen gaan gebruiken of hen vragen om zich te verifiëren zodra ze uw back-endservices gaan gebruiken.

Afdwingen dat de gebruiker zich opnieuw aanmeldt

Voor sommige scenario's wilt u mogelijk dat de gebruiker bewijst dat hij of zij de persoon is die momenteel is aangemeld, voordat hij of zij toegang krijgt tot de app of soms voordat hij een bepaalde actie in uw app uitvoert. Voordat een bank-app bijvoorbeeld de opdracht geld overmaken naar de server verzendt, wilt u ervoor zorgen dat het de gebruiker is, in plaats van iemand die een aangemeld apparaat heeft gevonden, een transactie probeert uit te voeren. U kunt afdwingen dat de gebruiker zich opnieuw aanmeldt in uw app met behulp van de klasse UserConsentVerifier . Met de volgende coderegel wordt de gebruiker gedwongen om zijn inloggegevens in te voeren.

Met de volgende coderegel wordt de gebruiker gedwongen om zijn inloggegevens in te voeren.

UserConsentVerificationResult consentResult = await UserConsentVerifier.RequestVerificationAsync("userMessage");

if (consentResult.Equals(UserConsentVerificationResult.Verified))

{

// continue

}

U kunt ook gebruikmaken van het challenge-response mechanisme van de server, waarbij de gebruiker zijn of haar pincode of biometrische gegevens moet invoeren. Dit is afhankelijk van het scenario dat u als ontwikkelaar moet implementeren. Dit mechanisme wordt beschreven in de volgende sectie.

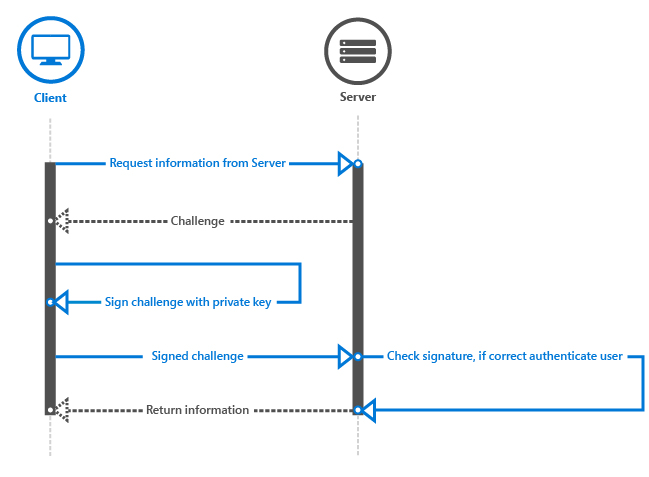

Verificatie in de back-end

Wanneer de app toegang probeert te krijgen tot een beveiligde back-endservice, verzendt de service een uitdaging naar de app. De app gebruikt de persoonlijke sleutel van de gebruiker om de uitdaging te ondertekenen en deze terug te sturen naar de server. Omdat de server de openbare sleutel voor die gebruiker heeft opgeslagen, worden standaard crypto-API's gebruikt om ervoor te zorgen dat het bericht inderdaad is ondertekend met de juiste persoonlijke sleutel. Op de client wordt de ondertekening uitgevoerd door de Windows Hello-API's; de ontwikkelaar heeft nooit toegang tot de persoonlijke sleutel van een gebruiker.

Naast het controleren van de sleutels, kan de service ook de sleutelverklaring controleren en zien of er beperkingen zijn die worden aangeroepen voor de manier waarop de sleutels op het apparaat worden opgeslagen. Wanneer het apparaat bijvoorbeeld TPM gebruikt om de sleutels te beveiligen, is het veiliger dan apparaten die de sleutels opslaan zonder TPM. De back-endlogica kan bijvoorbeeld besluiten dat de gebruiker alleen een bepaald bedrag mag overdragen wanneer er geen TPM wordt gebruikt om de risico's te verminderen.

Attestation is alleen beschikbaar voor apparaten met een TPM-chip die versie 2.0 of hoger is. Daarom moet u er rekening mee houden dat deze informatie mogelijk niet beschikbaar is op elk apparaat.

De clientwerkstroom kan er als volgt uitzien:

Wanneer de app de service aanroept op de back-end, verzendt de server een uitdaging. De uitdaging wordt ondertekend met de volgende code:

var openKeyResult = await KeyCredentialManager.OpenAsync(AccountId);

if (openKeyResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.Success)

{

var userKey = openKeyResult.Credential;

var publicKey = userKey.RetrievePublicKey();

var signResult = await userKey.RequestSignAsync(message);

if (signResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.Success)

{

return signResult.Result;

}

else if (signResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.UserPrefersPassword)

{

}

}

De eerste regel , KeyCredentialManager.OpenAsync, vraagt Windows om de sleutelgreep te openen. Als dat lukt, kunt u het vraagbericht ondertekenen met de methode KeyCredential.RequestSignAsync , waardoor Windows de pincode of biometrie van de gebruiker kan aanvragen via Windows Hello. Op geen enkel moment heeft de ontwikkelaar toegang tot de persoonlijke sleutel van de gebruiker. Dit wordt allemaal beveiligd via de API's.

De API's vragen Windows om de uitdaging te ondertekenen met de persoonlijke sleutel. Vervolgens vraagt het systeem de gebruiker om een pincode of een geconfigureerde biometrische aanmelding. Wanneer de juiste informatie wordt ingevoerd, kan het systeem de TPM-chip vragen om de cryptografische functies uit te voeren en de uitdaging te ondertekenen. (Of gebruik de terugvalsoftwareoplossing als er geen TPM beschikbaar is). De client moet de ondertekende uitdaging terugsturen naar de server.

In dit sequentiediagram wordt een basisstroom voor uitdagingsreacties weergegeven:

Vervolgens moet de server de handtekening valideren. Wanneer u de openbare sleutel aanvraagt en naar de server verzendt voor toekomstige validatie, bevindt deze zich in een met ASN.1 gecodeerde publicKeyInfo-blob. Als u het Windows Hello-codevoorbeeld op GitHub bekijkt, ziet u dat er helperklassen zijn voor het verpakken van Crypt32-functies om de ASN.1-gecodeerde blob te vertalen naar een CNG-blob, die vaker wordt gebruikt. De blob bevat het algoritme voor de openbare sleutel, rsa en de openbare RSA-sleutel.

In het voorbeeld converteren we de ASN.1-gecodeerde blob naar een CNG-blob, zodat deze kan worden gebruikt met CNG en de BCrypt-API. Als u de CNG-blob opzoekt, verwijst deze u naar de gerelateerde BCRYPT_KEY_BLOB structuur. Deze API-surface kan worden gebruikt voor verificatie en versleuteling in Windows-toepassingen. ASN.1 is een gedocumenteerde standaard voor het communiceren van gegevensstructuren die kunnen worden geserialiseerd en wordt vaak gebruikt in openbare-sleutelcryptografie en met certificaten. Daarom wordt de informatie van de openbare sleutel op deze manier geretourneerd. De openbare sleutel is een RSA-sleutel; en dat is het algoritme dat Windows Hello gebruikt wanneer deze gegevens ondertekent.

Zodra u de CNG-blob hebt, moet u de ondertekende uitdaging valideren tegen de openbare sleutel van de gebruiker. Omdat iedereen zijn of haar eigen systeem- of back-endtechnologie gebruikt, is er geen algemene manier om deze logica te implementeren. We gebruiken SHA256 als het hash-algoritme en Pkcs1 voor SignaturePadding, dus zorg ervoor dat dat is wat u gebruikt wanneer u het ondertekende antwoord van de client valideert. Raadpleeg het voorbeeld voor een manier om dit te doen op uw server in .NET 4.6, maar in het algemeen ziet het er ongeveer als volgt uit:

using (RSACng pubKey = new RSACng(publicKey))

{

retval = pubKey.VerifyData(originalChallenge, responseSignature, HashAlgorithmName.SHA256, RSASignaturePadding.Pkcs1);

}

We lezen de opgeslagen openbare sleutel, een RSA-sleutel. We valideren het ondertekende vraagbericht met de openbare sleutel en als dit wordt uitgecheckt, autoriseren we de gebruiker. Als de gebruiker is geverifieerd, kan de app de back-endservices als normaal aanroepen.

De volledige code kan er ongeveer als volgt uitzien:

using System;

using System.Runtime;

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using Windows.Storage.Streams;

using Windows.Security.Cryptography;

using Windows.Security.Cryptography.Core;

using Windows.Security.Credentials;

static async Task<IBuffer> GetAuthenticationMessageAsync(IBuffer message, String AccountId)

{

var openKeyResult = await KeyCredentialManager.OpenAsync(AccountId);

if (openKeyResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.Success)

{

var userKey = openKeyResult.Credential;

var publicKey = userKey.RetrievePublicKey();

var signResult = await userKey.RequestSignAsync(message);

if (signResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.Success)

{

return signResult.Result;

}

else if (signResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.UserCanceled)

{

// Launch app-specific flow to handle the scenario

return null;

}

}

else if (openKeyResult.Status == KeyCredentialStatus.NotFound)

{

// PIN reset has occurred somewhere else and key is lost.

// Repeat key registration

return null;

}

else

{

// Show custom UI because unknown error has happened.

return null;

}

}

Het implementeren van het juiste mechanisme voor uitdaging-respons valt buiten het bereik van dit document, maar dit onderwerp is iets dat aandacht vereist om een beveiligd mechanisme te maken om zaken als herhalingsaanvallen of man-in-the-middle-aanvallen te voorkomen.

Een ander apparaat inschrijven

Het is gebruikelijk dat gebruikers meerdere apparaten hebben waarop dezelfde apps zijn geïnstalleerd. Hoe werkt dit wanneer u Windows Hello gebruikt met meerdere apparaten?

Wanneer u Windows Hello gebruikt, maakt elk apparaat een unieke persoonlijke en openbare sleutelset. Dit betekent dat als u wilt dat een gebruiker meerdere apparaten kan gebruiken, uw back-end meerdere openbare sleutels van deze gebruiker moet kunnen opslaan. Raadpleeg het databasediagram in de sectie Nieuwe gebruikers inschrijven voor een voorbeeld van de tabelstructuur.

Het registreren van een ander apparaat is bijna hetzelfde als het registreren van een gebruiker voor het eerst. U moet er nog steeds voor zorgen dat de gebruiker die zich registreert voor dit nieuwe apparaat, de gebruiker is die hij of zij claimt. U kunt dit doen met elk mechanisme voor tweeledige verificatie dat momenteel wordt gebruikt. Er zijn verschillende manieren om dit op een veilige manier te bereiken. Het hangt allemaal af van uw scenario.

Als u bijvoorbeeld nog steeds de aanmeldingsnaam en het wachtwoord gebruikt, kunt u deze gebruiken om de gebruiker te verifiëren en hen te vragen een van hun verificatiemethoden te gebruiken, zoals sms of e-mail. Als u geen aanmeldingsnaam en wachtwoord hebt, kunt u ook een van de al geregistreerde apparaten gebruiken en een melding verzenden naar de app op dat apparaat. De MSA Authenticator-app is een voorbeeld hiervan. Kortom, u moet een gemeenschappelijk 2FA-mechanisme gebruiken om extra apparaten voor de gebruiker te registreren.

De code voor het registreren van het nieuwe apparaat is precies hetzelfde als het voor het eerst registreren van de gebruiker (vanuit de app).

var keyCreationResult = await KeyCredentialManager.RequestCreateAsync(

AccountId, KeyCredentialCreationOption.ReplaceExisting);

Om het voor de gebruiker gemakkelijker te maken om te herkennen welke apparaten zijn geregistreerd, kunt u ervoor kiezen om de apparaatnaam of een andere id als onderdeel van de registratie te verzenden. Dit is bijvoorbeeld ook handig als u een service op uw back-end wilt implementeren waar gebruikers de registratie van apparaten kunnen opheffen wanneer een apparaat verloren gaat.

Meerdere accounts in uw app gebruiken

Naast het ondersteunen van meerdere apparaten voor één account, is het ook gebruikelijk om meerdere accounts in één app te ondersteunen. Stel dat u vanuit uw app verbinding maakt met meerdere Twitter-accounts. Met Windows Hello kunt u meerdere sleutelparen maken en meerdere accounts in uw app ondersteunen.

Een manier om dit te doen is door de gebruikersnaam of unieke identificator, beschreven in de vorige sectie, op geïsoleerde opslag te bewaren. Elke keer dat u een nieuw account maakt, slaat u de account-id daarom op in geïsoleerde opslag.

In de gebruikersinterface van de app kan de gebruiker een van de eerder gemaakte accounts kiezen of zich registreren met een nieuwe account. Het proces voor het maken van een nieuw account is hetzelfde als eerder beschreven. Het kiezen van een account is een kwestie van het weergeven van de opgeslagen accounts op het scherm. Zodra de gebruiker een account heeft geselecteerd, gebruikt u de account-id om u aan te melden bij de gebruiker in uw app:

var openKeyResult = await KeyCredentialManager.OpenAsync(AccountId);

De rest van de stroom is hetzelfde als eerder beschreven. Om duidelijk te zijn, worden al deze accounts beveiligd door dezelfde pincode of biometrische beweging, omdat in dit scenario ze worden gebruikt op één apparaat met hetzelfde Windows-account.

Een bestaand systeem migreren naar Windows Hello

In deze korte sectie behandelen we een bestaand verpakt app- en back-endsysteem dat gebruikmaakt van een database waarin de gebruikersnaam en het hash-wachtwoord worden opgeslagen. Deze apps verzamelen referenties van de gebruiker wanneer de app start en gebruiken ze wanneer het back-endsysteem de authenticatievraag retourneert.

Hier beschrijven we welke onderdelen moeten worden gewijzigd of vervangen om Windows Hello te laten werken.

We hebben de meeste technieken in de eerdere secties al beschreven. Het toevoegen van Windows Hello aan uw bestaande systeem omvat het toevoegen van een aantal verschillende stromen in het registratie- en verificatiegedeelte van uw code.

Een benadering is om de gebruiker te laten kiezen wanneer de upgrade moet worden uitgevoerd. Nadat de gebruiker zich heeft aanmeldt bij de app en u detecteert dat de app en het besturingssysteem Windows Hello kunnen ondersteunen, kunt u de gebruiker vragen of hij of zij referenties wil upgraden om dit moderne en veiligere systeem te gebruiken. U kunt de volgende code gebruiken om te controleren of de gebruiker Windows Hello kan gebruiken.

var keyCredentialAvailable = await KeyCredentialManager.IsSupportedAsync();

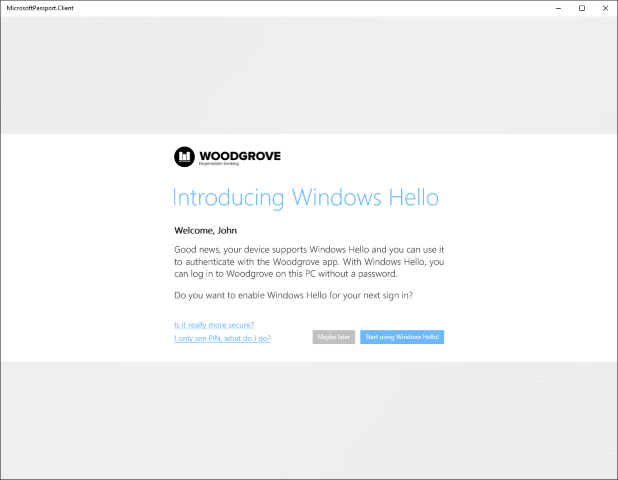

De gebruikersinterface ziet er ongeveer als volgt uit:

Als de gebruiker ervoor kiest om Windows Hello te gaan gebruiken, maakt u de KeyCredential die eerder is beschreven. De back-endregistratieserver voegt de openbare sleutel en de optionele attestatieverklaring toe aan de database. Omdat de gebruiker al is geverifieerd met gebruikersnaam en wachtwoord, kan de server de nieuwe referenties koppelen aan de huidige gebruikersgegevens in de database. Het databasemodel kan hetzelfde zijn als het voorbeeld dat eerder is beschreven.

Als de app de gebruikers KeyCredential kon maken, wordt de gebruikers-id opgeslagen in geïsoleerde opslag, zodat de gebruiker dit account kan kiezen in de lijst zodra de app opnieuw is gestart. Vanaf dit punt volgt de stroom precies de voorbeelden die in eerdere secties worden beschreven.

De laatste stap bij het migreren naar een volledig Windows Hello-scenario is het uitschakelen van de aanmeldingsnaam en wachtwoordoptie in de app en het verwijderen van de opgeslagen hash-wachtwoorden uit uw database.

Samenvatting

Windows introduceert een hoger beveiligingsniveau dat ook eenvoudig in de praktijk kan worden gebracht. Windows Hello biedt een nieuw biometrisch aanmeldingssysteem dat de gebruiker herkent en actief pogingen voorkomt om de juiste identificatie te omzeilen. Het kan vervolgens meerdere lagen sleutels en certificaten leveren die nooit buiten de vertrouwde platformmodule kunnen worden weergegeven of gebruikt. Daarnaast is er een verdere beveiligingslaag beschikbaar via het optionele gebruik van attestation-identiteitssleutels en -certificaten.

Als ontwikkelaar kunt u deze richtlijnen gebruiken voor het ontwerpen en implementeren van deze technologieën om eenvoudig beveiligde verificatie toe te voegen aan uw verpakte Windows-app-implementaties om apps en back-endservices te beveiligen. De vereiste code is minimaal en gemakkelijk te begrijpen. Windows verwerkt het zware werk.

Met flexibele implementatieopties kan Windows Hello uw bestaande verificatiesysteem vervangen of er samen mee werken. De implementatie-ervaring is pijnloos en economisch. Er is geen extra infrastructuur nodig om Windows-beveiliging te implementeren. Met Microsoft Hello ingebouwd in het besturingssysteem biedt Windows de veiligste oplossing voor de verificatieproblemen die de moderne ontwikkelaar ondervindt.

Missie volbracht! Je hebt net internet een veiligere plek gemaakt!

Aanvullende bronnen

Artikelen en voorbeeldcode

- Overzicht van Windows Hello

- Een Implementatie van Windows Hello voor Bedrijven plannen

- Windows Hello UWP-codevoorbeeld op GitHub

Terminologie

| Termijn | Definitie |

|---|---|

| AIK | Een attestation-identiteitssleutel wordt gebruikt om een dergelijk cryptografisch bewijs (TPM-sleutelverklaring) te leveren door de eigenschappen van de niet-migrerende sleutel te ondertekenen en de eigenschappen en handtekening aan de relying party te verstrekken voor verificatie. De resulterende handtekening wordt een attestatieverklaring genoemd. Omdat de handtekening wordt gemaakt met behulp van de persoonlijke AIK-sleutel, die alleen kan worden gebruikt in de TPM die deze heeft gemaakt, kan de relying party vertrouwen dat de geteste sleutel echt niet kan worden gemigreerd en niet kan worden gebruikt buiten die TPM. |

| AIK-certificaat | Een AIK-certificaat wordt gebruikt om de aanwezigheid van een AIK binnen een TPM te bevestigen. Het wordt ook gebruikt om te bevestigen dat andere sleutels die zijn gecertificeerd door de AIK afkomstig zijn van die specifieke TPM. |

| IDP (intern ontheemd persoon) | Een IDP is een id-provider. Een voorbeeld is de IDP-build van Microsoft voor Microsoft-accounts. Telkens wanneer een toepassing moet worden geverifieerd met een MSA, kan deze de MSA IDP aanroepen. |

| PKI | Openbare-sleutelinfrastructuur wordt vaak gebruikt om te verwijzen naar een omgeving die wordt gehost door een organisatie zelf en verantwoordelijk is voor het maken van sleutels, het intrekken van sleutels, enzovoort. |

| TPM (Trusted Platform Module) | De vertrouwde platformmodule kan worden gebruikt om cryptografische openbare/persoonlijke sleutelparen te maken op een zodanige manier dat de persoonlijke sleutel nooit kan worden weergegeven of gebruikt buiten de TPM (de sleutel kan dus niet worden gemigreerd). |

| TPM-sleutelverklaring | Een protocol dat cryptografisch bewijst dat een sleutel TPM-gebonden is. Dit type attestation kan worden gebruikt om te garanderen dat een bepaalde cryptografische bewerking heeft plaatsgevonden in de TPM van een bepaalde computer |

Verwante onderwerpen

Windows developer