Blue-green deployment strategies in Azure Spring Apps

Note

The Basic, Standard, and Enterprise plans will be deprecated starting from mid-March, 2025, with a 3 year retirement period. We recommend transitioning to Azure Container Apps. For more information, see the Azure Spring Apps retirement announcement.

The Standard consumption and dedicated plan will be deprecated starting September 30, 2024, with a complete shutdown after six months. We recommend transitioning to Azure Container Apps. For more information, see Migrate Azure Spring Apps Standard consumption and dedicated plan to Azure Container Apps.

This article applies to: ✔️ Basic/Standard ✔️ Enterprise

This article describes the blue-green deployment support in Azure Spring Apps.

Azure Spring Apps (Standard plan and higher) permits two deployments for every app, only one of which receives production traffic. This pattern is commonly known as blue-green deployment. Azure Spring Apps's support for blue-green deployment, together with a Continuous Delivery (CD) pipeline and rigorous automated testing, allows agile application deployments with high confidence.

Alternating deployments

The simplest way to implement blue-green deployment with Azure Spring Apps is to create two fixed deployments and always deploy to the deployment that isn't receiving production traffic. With the Azure Spring Apps task for Azure Pipelines, you can deploy this way just by setting the UseStagingDeployment flag to true.

Here's how the alternating deployments approach works in practice:

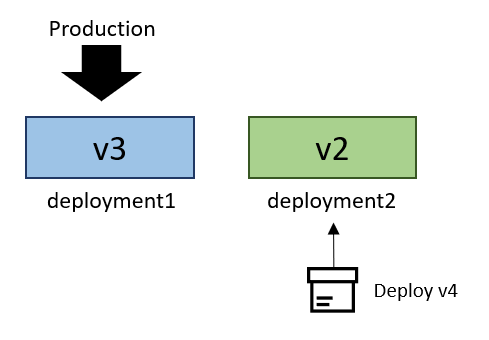

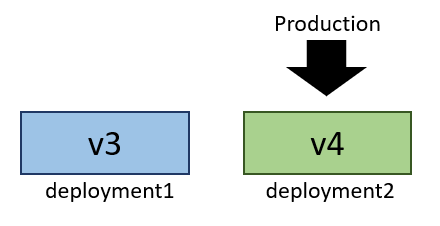

Suppose your application has two deployments: deployment1 and deployment2. Currently, deployment1 is set as the production deployment, and is running version v3 of the application.

This makes deployment2 the staging deployment. Thus, when the Continuous Delivery (CD) pipeline is ready to run, it deploys the next version of the app, version v4, onto the staging deployment deployment2.

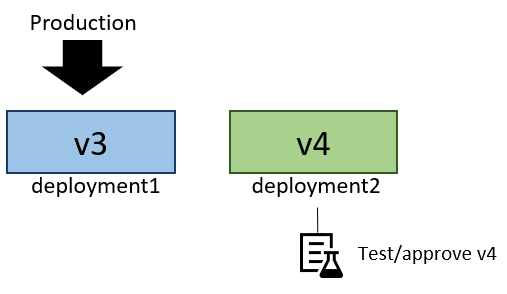

After v4 has started up on deployment2, you can run automated and manual tests against it through a private test endpoint to ensure v4 meets all expectations.

When you have confidence in v4, you can set deployment2 as the production deployment so that it receives all production traffic. v3 will remain running on deployment1 in case you discover a critical issue that requires rolling back.

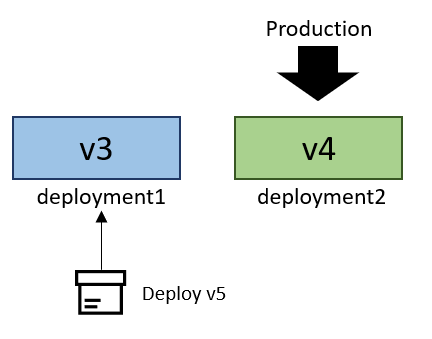

Now, deployment1 is the staging deployment. So the next run of the deployment pipeline deploys onto deployment1.

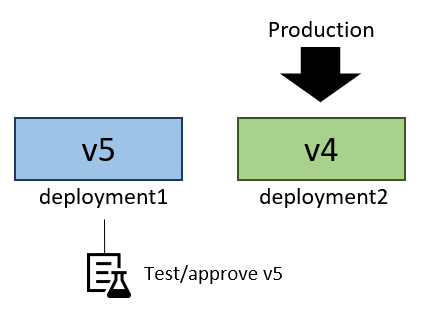

You can now test V5 on deployment1's private test endpoint.

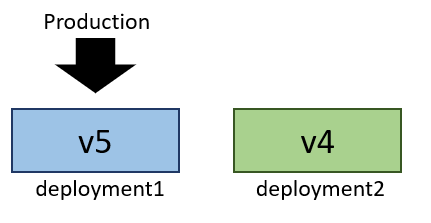

Finally, after v5 meets all your expectations, you set deployment1 as the production deployment once again, so that v5 receives all production traffic.

Tradeoffs of the alternating deployments approach

The alternating deployments approach is simple and fast, as it doesn't require the creation of new deployments. However, it does present several disadvantages, as described in the following sections.

Persistent staging deployment

The staging deployment always remains running, and thus consuming resources of the Azure Spring Apps instance. This effectively doubles the resource requirements of each application on Azure Spring Apps.

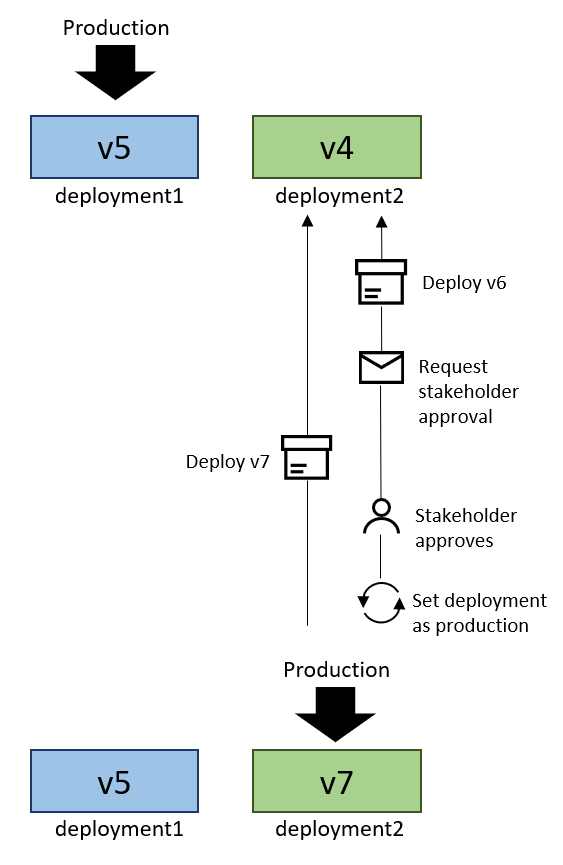

The approval race condition

Suppose in the above application, the release pipeline requires manual approval before each new version of the application can receive production traffic. This creates the risk that while one version (v6) awaits manual approval on the staging deployment, the deployment pipeline will run again and overwrite it with a newer version (v7). Then, when the approval for v6 is granted, the pipeline that deployed v6 will set the staging deployment as production. But now it will be the unapproved v7, not the approved v6, that is deployed on that deployment and receives traffic.

You may be able to prevent the race condition by ensuring that the deployment flow for one version can't begin until the deployment flow for all previous versions is complete or aborted. Another way to prevent the approval race condition is to use the Named Deployments approach described below.

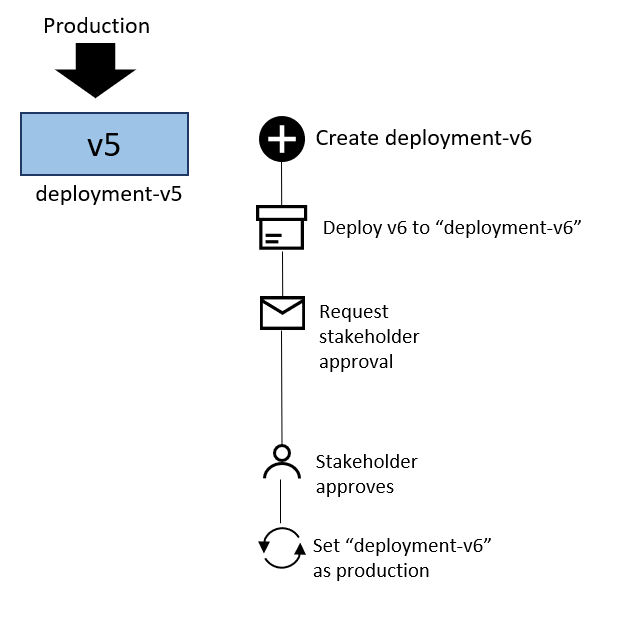

Named deployments

In the named deployments approach, a new deployment is created for each new version of the application being deployed. After the application is tested on its bespoke deployment, that deployment is set as the production deployment. The deployment containing the previous version can be allowed to persist just long enough to be confident that a rollback won't be needed.

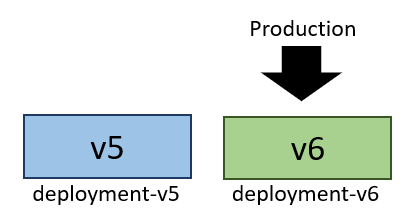

In the illustration below, version v5 is running on the deployment deployment-v5. The deployment name now contains the version because the deployment was created specifically for this version. There's no other deployment at the outset. Now, to deploy version v6, the deployment pipeline creates a new deployment deployment-v6 and deploys app version v6 there.

There's no risk of another version being deployed in parallel. First, Azure Spring Apps doesn't allow the creation of a third deployment while two deployments already exist. Second, even if it was possible to have more than two deployments, each deployment is identified by the version of the application it contains. Thus, the pipeline orchestrating the deployment of v6 would only attempt to set deployment-v6 as the production deployment.

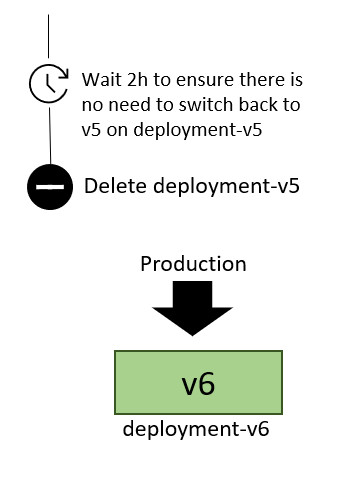

After the deployment created for the new version receives production traffic, you'll need to remove the deployment containing the previous version to make room for future deployments. You may wish to postpone by some number of minutes or hours so you can roll back to the previous version if you discover a critical issue in the new version.

Tradeoffs of the named deployments approach

The named deployments approach has the following benefits:

- It prevents the approval race condition.

- It reduces resource consumption by deleting the staging deployment when it's not in use.

However, there are drawbacks as well, as described in the following section.

Deployment pipeline failures

Between the time a deployment starts and the time the staging deployment is deleted, any additional attempts to run the deployment pipeline will fail. The pipeline will attempt to create a new deployment, which will result in an error because only two deployments are permitted per application in Azure Spring Apps.

Therefore, the deployment orchestration must either have the means to retry a failed deployment process at a later time, or the means to ensure that the deployment flows for each version will remain queued until the flow is completed for all previous versions.