Creating a new Rembrandt with big data

By Dan Oliver, Editor-in-chief at Creative Bloq

Big data. Machine learning. As emerging areas of technology, these are hugely engaging topics for developers, and push the boundaries of what humans can achieve through computing. However, not everyone feels positively about them, and despite the fact that we're still scratching the surface of what we're able to achieve with cognitive computing, there's already a certain amount of suspicion that's grown up around it (with marketing and surveillance often cited as primary use cases).

It was with this in mind that advertising agency JWT, together with Dutch financial giant ING, embarked on a new project that would use data in a way that no one had seen before - in a way that would showcase cognitive computing's creative potential, and change the perception of what could be achieved with big data.

"Around 10 months ago Bas Korsten, who is my creative director at JWT Amsterdam, came to me and said "Can you please take a look into this project, and tell me how viable it is?". And the brief was this: make a new Rembrandt out of data. Easy, right?," explains Emmanuel Flores, the Director of Technology on The Next Rembrandt project.

The idea had been floating around JWT for a few years, having started with a conversation with its client ING about how to showcase innovation. ING wanted to focus on a Dutch icon, and use big data to tell that story.

"But even then there was a negative perception around what big data is, and how it's used," says Flores. "Our challenge was to change that perception, and create an engaging story."

It's almost 350 years since the man many believe to be our greatest artist created his last image, and trying to isolate Rembrandt's creative DNA was uncharted territory.

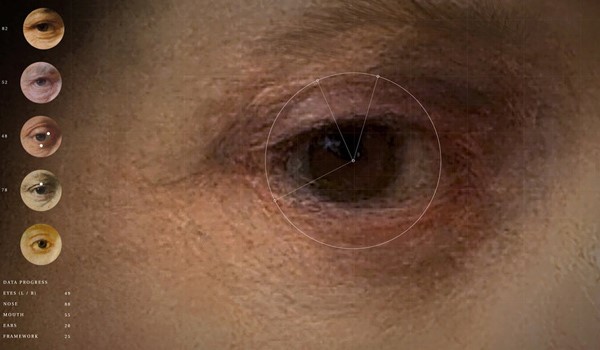

"With these kind of projects you look back and you don't see anything, because it's never been done before. And you look forward, and there's no road map. But I actually like that," says Flores. "You have no idea if it will work. So we started making a prototype, which was basically extracting data from a collection of paintings from Rembrandt, in order to create a single facial feature."

Initially the team studied the contents of 324 paintings, pixel by pixel, and then narrowed down exploration to portraits (as they made up 44% of Rembrandt's entire collection, more than any other subject he painted).

But there was still no proof-of-concept. And before the team could progress, and get the full backing of both the client and agency, they would need to produce a data-generated facial feature in the style of Rembrandt.

"I remember the moment when it hit me," Flores tells us. "I was traveling back from China [where Emmanuel works as a visiting professor], and I had received an email from one of my team, and when I opened it I saw the result of the code: an eye. And I thought to myself, "Oh my god! We can do this!". I knew it would be very painful, but at that point I also knew we had the skills and knowledge to get it done."

Based on the abundance of portrait-based data they had at their disposal, the team would attempt to create an image of a white, moustached male, between the ages of thirty and forty, wearing black clothes, with a white collar and a hat, facing to the right, and lit strongly from above by a single light source.

"We analysed the sizes of the faces. We analysed light, the properties of shadows, the backgrounds. hair, eyes, mouths, everything that we could that was a compositional component. We created a system that learned the data and could create a new portrait out of it," says Flores.

And there was a huge amount of data to work with, with the final piece alone being made up of 148 million pixels, and 168,263 separate image fragments from other works. To make sense of it all, and enable the complicated algorithms to query this data, JWT turned to Microsoft's Azure platform.

"We were using the Azure platform, which was a huge help, as we were having to manage large amounts of data," says Flores. "The amount of data we generated was about 300GB. But the algorithms were the issue. It wasn't so much about data, but having the power to analyse that data, and drill down to multiple levels. Azure had different elements that we put into play, most notably device sharing and storage. And we were also really impressed with the platform's flexibility, enabling us to write algorithms to filter data and write to multiple databases at speed."

To deal with the amount of processing and data handling that was required, the team set up rendering farms, and used Azure to distribute processing across a cluster of machines.

"When you consider that the final image took 500 hours of rendering time, it's obvious to see how important rendering farms were. It was an insane amount of data handling. And putting it in a farm made things far more efficient, as every minute was fundamental," Flores explains. "We also learned a huge amount from the Microsoft team on how to improve our processes. There's something changing in Microsoft, and I don't know where it's coming from, but I felt it. I was like, "Woah, these people are thinking like hackers!", which surprised me."

And as the team increased the amount of reference data that the learning algorithms could query, interesting and unexpected patterns began to emerge.

"We told the system what to pay attention to, but this was done by filtering. We weren't controlling the output, that was all down to the machine. And as we progressed, we started to get surprises coming back. These surprises came from Rembrandt himself. When we were generating some of the features we were getting details that we'd never envisaged, such as super-detailed facial hair, and I was wondering where has this small moustache come from?!"

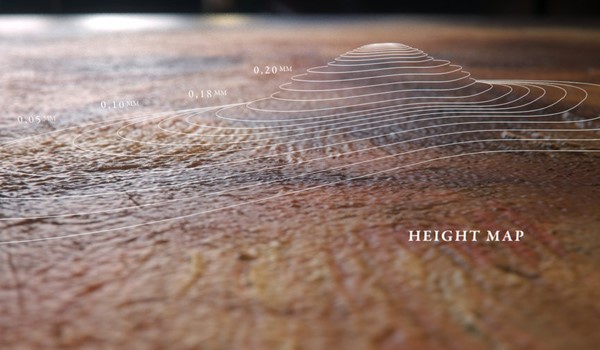

Once the technology behind creating the image was in place, the team turned its attention to the 3D phase, where it would attempt to replicate Rembrandt's brush stroke and canvas details.

"We weren't just having to consider paint, but elements such as the canvas and its weave, as well as how the ground layer had been prepared," says Flores. "We analysed the ground layer, the canvas, and then the brushing."

The 3D printing required a custom-made printer and scanning setup, that used special UV ink which could be layered in a way that gave the finished artwork the appearance of having being created with real paint.

To build up this 3D data the team had to use x-ray analysis to interpret the brushing patterns of Rembrandt. And as they dug deeper, they began to build a deeper understanding of Rembrandt, which went beyond pure pixels.

"Rembrandt was such a complex painter for us to study, because he's not linear," Flores says. "You can see paintings from within the same period with totally different brushing styles. So we were able to get a feel for the commercial Rembrandt, the Rembrandt who is creating something to be sold, and the Rembrandt who is exploring."

And it's this facet of machine learning that Flores is truly drawn to. The ability to create a new piece of work is what captured the imagination of the media and the public, but it's the deeper understanding of our greatest artists that could be the project's lasting legacy.

"Rembrandt is-from an art perspective-a monster, he's fantastic. But I would also love to try and recreate the style of Caravaggio. Not only because I find him a fascinating painter, but also because he had a strong influence on Rembrandt, so in a way we'd be putting together another link to him," Flores tells us. "It might not be that we'd create another painting in the style of Caravaggio, but maybe we can answer stylistic questions, and we might find that the data tells us Rembrandt wasn't as influenced by Caravaggio as we've always thought. Alternatively, we might make more connections between these two masters."

However, despite what we can learn about our greatest artists using cognitive computing, there has been a mixed reaction from the art fraternity.

"Some people love it," Flores says. "But we have touched something very sacred to them, and I guess if you are a creative you may not be willing to accept that a machine can be creative, too. We had some criticism about mimicking Rembrandt, but it was totally missing the point, because I'm not making a Rembrandt, I'm making a visualisation of the data coming out of Rembrandt. It's about knowledge, not trying to claim territory.

"We're OK when the machine is clearly defined as the tool, but what happens when the extension becomes more organic, and starts to interact with you on a different level?"

One of the most interesting facets of the future of cognitive computing is whether people can accept living with it, and there's a fundamental question around whether we are we open minded enough to use this technology in more creative ways. But Flores' position is clear: "I still look at it as a tool," he concludes. "Nothing will ever top human artistry."

- Do more with Azure - With new computing capabilities decreasing costs and increasing flexibility, many IT professionals and developers find themselves able to try new things. Discover and experiment by building your first workload on Azure.

- Building Blocks: Big Data and Machine Learning

- Applications on Azure: Putting All the Pieces Together

- Data Science and Machine Learning Essentials