Events

Mar 31, 11 PM - Apr 2, 11 PM

The biggest SQL, Fabric and Power BI learning event. March 31 – April 2. Use code FABINSIDER to save $400.

Register todayThis browser is no longer supported.

Upgrade to Microsoft Edge to take advantage of the latest features, security updates, and technical support.

Applies to:

SQL Server

Azure SQL Database

Azure SQL Managed Instance

Full-Text Search in SQL Server and Azure SQL Database lets users and applications run full-text queries against character-based data in SQL Server tables.

This article provides an overview of Full-Text Search and describes its components and its architecture. If you prefer to get started right away, here are the basic tasks.

Full-Text Search is an optional component of the SQL Server Database Engine. If you didn't select Full-Text Search when you installed SQL Server, run SQL Server Setup again to add it.

A full-text index includes one or more character-based columns in a table. These columns can have any of the following data types: char, varchar, nchar, nvarchar, text, ntext, image, xml, or varbinary(max) and FILESTREAM. Each full-text index indexes one or more columns from the table, and each column can use a specific language.

Full-text queries perform linguistic searches against text data in full-text indexes, by operating on words and phrases based on the rules of a particular language, such as English or Japanese. Full-text queries can include simple words and phrases or multiple forms of a word or phrase. A full-text query returns any documents that contain at least one match (also known as a hit). A match occurs when a target document contains all the terms specified in the full-text query, and meets any other search conditions, such as the distance between the matching terms.

After columns are added to a full-text index, users and applications can run full-text queries on the text in the columns. These queries can search for any of the following conditions:

Full-text queries aren't case-sensitive. For example, searching for Aluminum or aluminum returns the same results.

Full-text queries use a small set of Transact-SQL predicates (CONTAINS and FREETEXT) and functions (CONTAINSTABLE and FREETEXTTABLE). However, the search goals of a given business scenario influence the structure of the full-text queries. For example:

Searching for a product on an E-commerce website:

SELECT product_id

FROM products

WHERE CONTAINS (product_description, '"Snap Happy 100EZ" OR FORMSOF(THESAURUS,"Snap Happy") OR "100EZ"')

AND product_cost < 200;

Recruitment scenario-searching for job candidates that have experience working with SQL Server:

SELECT candidate_name,

SSN

FROM candidates

WHERE CONTAINS (candidate_resume, '"SQL Server"')

AND candidate_division = 'DBA';

For more information, see Query with Full-Text Search.

In contrast to full-text search, the LIKE Transact-SQL predicate works on character patterns only. Also, you can't use the LIKE predicate to query formatted binary data. Furthermore, a LIKE query against a large amount of unstructured text data is much slower than an equivalent full-text query against the same data. A LIKE query against millions of rows of text data can take minutes to return; whereas a full-text query can take only seconds or less against the same data, depending on the number of rows that are returned.

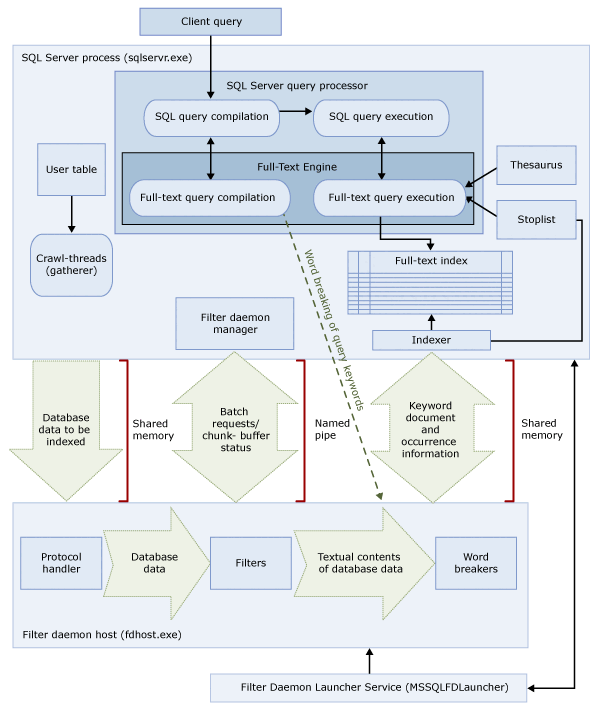

Full-text search architecture consists of the following processes:

The SQL Server process (sqlservr.exe).

The filter daemon host process (fdhost.exe).

For security reasons, filters are loaded by separate processes called the filter daemon hosts. The fdhost.exe processes are created by an FDHOST launcher service (MSSQLFDLauncher), and they run under the security credentials of the FDHOST launcher service account. Therefore, the FDHOST launcher service must be running for full-text indexing and full-text querying to work. For information about setting the service account for this service, see Set the Service Account for the Full-text Filter Daemon Launcher.

These two processes contain the components of the full-text search architecture. These components and their relationships are summarized in the following illustration. The components are described after the illustration.

The SQL Server process uses the following components for full-text search:

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| User tables | These tables contain the data to be full-text indexed. |

| Full-text gatherer | The full-text gatherer works with the full-text crawl threads. It's responsible for scheduling and driving the population of full-text indexes, and also for monitoring full-text catalogs. |

| Thesaurus files | These files contain synonyms of search terms. For more information, see Configure and Manage Thesaurus Files for Full-Text Search. |

| Stoplist objects | Stoplist objects contain a list of common words that aren't useful for the search. For more information, see Configure and Manage Stopwords and Stoplists for Full-Text Search. |

| SQL Server query processor | The query processor compiles and executes SQL queries. If a SQL query includes a full-text search query, the query is sent to the Full-Text Engine, both during compilation and during execution. The query result is matched against the full-text index. |

| Full-Text Engine | The Full-Text Engine in SQL Server is fully integrated with the query processor. The Full-Text Engine compiles and executes full-text queries. As part of query execution, the Full-Text Engine might receive input from the thesaurus and stoplist. |

| Index writer (indexer) | The index writer builds the structure that is used to store the indexed tokens. |

| Filter daemon manager | The filter daemon manager is responsible for monitoring the status of the Full-Text Engine filter daemon host. |

The filter daemon host is a process that is started by the Full-Text Engine. It runs the following full-text search components, which are responsible for accessing, filtering, and word breaking data from tables, as well as for word breaking and stemming the query input.

The components of the filter daemon host are as follows:

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Protocol handler | This component pulls the data from memory for further processing and accesses data from a user table in a specified database. One of its responsibilities is to gather data from the columns being full-text indexed and pass it to the filter daemon host, which applies filtering and word breaker as required. |

| Filters | Some data types require filtering before the data in a document can be full-text indexed, including data in varbinary, varbinary(max), image, or xml columns. The filter used for a given document depends on its document type. For example, different filters are used for Microsoft Word (.doc) documents, Microsoft Excel (.xls) documents, and XML (.xml) documents. Then the filter extracts chunks of text from the document, removing embedded formatting and retaining the text and, potentially, information about the position of the text. The result is a stream of textual information. For more information, see Configure and Manage Filters for Search. |

| Word breakers and stemmers | A word breaker is a language-specific component that finds word boundaries based on the lexical rules of a given language (word breaking). Each word breaker is associated with a language-specific stemmer component that conjugates verbs and performs inflectional expansions. At indexing time, the filter daemon host uses a word breaker and stemmer to perform linguistic analysis on the textual data from a given table column. The language that is associated with a table column in the full-text index determines which word breaker and stemmer are used for indexing the column. For more information, see Configure & manage word breakers & stemmers for search (SQL Server). |

SQL Server 2012 (11.x) installs a new version of the word breakers and stemmers for US English (LCID 1033) and UK English (LCID 2057). However you can switch to the previous version of these components if you want to retain the previous behavior. For more information, see Change the Word Breaker Used for US English and UK English.

Full-text search is powered by the Full-Text Engine. The Full-Text Engine has two roles: indexing support and querying support.

When a full-text population (also known as a crawl) is initiated, the Full-Text Engine pushes large batches of data into memory and notifies the filter daemon host. The host filters and word-breaks the data and converts the converted data into inverted word lists. The full-text search then pulls the converted data from the word lists, processes the data to remove stopwords, and persists the word lists for a batch into one or more inverted indexes.

When indexing data stored in a varbinary(max) or image column, the filter, which implements the IFilter interface, extracts text based on the specified file format for that data (for example, Microsoft Word). In some cases, the filter components require the varbinary(max), or image data to be written out to the filterdata folder, instead of being pushed into memory.

As part of processing, the gathered text data is passed through a word breaker to separate the text into individual tokens, or keywords. The language used for tokenization is specified at the column level, or can be identified within varbinary(max), image, or xml data by the filter component.

Extra processing might be performed to remove stopwords, and to normalize tokens before they're stored in the full-text index or an index fragment.

When a population is complete, a final merge process is triggered that merges the index fragments together into one master full-text index. This results in improved query performance since only the master index needs to be queried rather than several index fragments, and better scoring statistics might be used for relevance ranking.

The query processor passes the full-text portions of a query to the Full-Text Engine for processing. The Full-Text Engine performs word breaking and, optionally, thesaurus expansions, stemming, and stopword (noise-word) processing. Then the full-text portions of the query are represented in the form of SQL operators, primarily as streaming table-valued functions (STVFs). During query execution, these STVFs access the inverted index to retrieve the correct results. The results are either returned to the client at this point, or they're further processed before being returned to the client.

The information in full-text indexes is used by the Full-Text Engine to compile full-text queries that can quickly search a table for particular words or combinations of words. A full-text index stores information about significant words and their location within one or more columns of a database table. A full-text index is a special type of token-based functional index that is built and maintained by the Full-Text Engine for SQL Server. The process of building a full-text index differs from building other types of indexes. Instead of constructing a B-tree structure based on a value stored in a particular row, the Full-Text Engine builds an inverted, stacked, compressed index structure based on individual tokens from the text being indexed. The size of a full-text index is limited only by the available memory resources of the computer on which the instance of SQL Server is running.

Beginning in SQL Server 2008 (10.0.x), the full-text indexes are integrated with the Database Engine, instead of residing in the file system as in previous versions of SQL Server. For a new database, the full-text catalog is now a virtual object that doesn't belong to any filegroup; it's merely a logical concept that refers to a group of the full-text indexes. Note, however, that during upgrade of a SQL Server 2005 (9.x) database, any full-text catalog that contains data files, a new filegroup is created; for more information, see Upgrade Full-Text Search.

Only one full-text index is allowed per table. For a full-text index to be created on a table, the table must have a single, unique non-null column. You can build a full-text index on columns of type char, varchar, nchar, nvarchar, text, ntext, image, xml, varbinary, and varbinary(max) can be indexed for full-text search. Creating a full-text index on a column whose data type is varbinary, varbinary(max), image, or xml requires that you specify a type column. A type column is a table column in which you store the file extension (.doc, .pdf, .xls, and so forth) of the document in each row.

A good understanding of the structure of a full-text index helps you understand how the Full-Text Engine works. This article uses the following excerpt of the Document table in AdventureWorks2022 as an example table. This excerpt shows only two columns, the DocumentID column and the Title column, and three rows from the table.

For this example, we assume that a full-text index has been created on the Title column.

| DocumentID | Title |

|---|---|

1 |

Crank Arm and Tire Maintenance |

2 |

Front Reflector Bracket and Reflector Assembly 3 |

3 |

Front Reflector Bracket Installation |

For example, the following table, which shows Fragment 1, depicts the contents of the full-text index created on the Title column of the Document table. Full-text indexes contain more information than is presented in this table. The table is a logical representation of a full-text index and is provided for demonstration purposes only. The rows are stored in a compressed format to optimize disk usage.

The data is inverted from the original documents. Inversion occurs because the keywords are mapped to the document IDs. For this reason, a full-text index is often referred to as an inverted index.

Also notice that the keyword and is removed from the full-text index. This is done because and is a stopword, and removing stopwords from a full-text index can lead to substantial savings in disk space, which improves query performance. For more information about stopwords, see Configure and Manage Stopwords and Stoplists for Full-Text Search.

Fragment 1

| Keyword | ColId | DocId | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

Crank |

1 | 1 | 1 |

Arm |

1 | 1 | 2 |

Tire |

1 | 1 | 4 |

Maintenance |

1 | 1 | 5 |

Front |

1 | 2 | 1 |

Front |

1 | 3 | 1 |

Reflector |

1 | 2 | 2 |

Reflector |

1 | 2 | 5 |

Reflector |

1 | 3 | 2 |

Bracket |

1 | 2 | 3 |

Bracket |

1 | 3 | 3 |

Assembly |

1 | 2 | 6 |

3 |

1 | 2 | 7 |

Installation |

1 | 3 | 4 |

The Keyword column contains a representation of a single token extracted at indexing time. Word breakers determine what makes up a token.

The ColId column contains a value that corresponds to a particular column that is full-text indexed.

The DocId column contains values for an 8-byte integer that maps to a particular full-text key value in a full-text indexed table. This mapping is necessary when the full-text key isn't an integer data type. In such cases, mappings between full-text key values and DocId values are maintained in a separate table called the DocId Mapping table. To query for these mappings, use the sp_fulltext_keymappings system stored procedure. To satisfy a search condition, DocId values from the previous table need to be joined with the DocId mapping table to retrieve rows from the base table being queried. If the full-text key value of the base table is an integer type, the value directly serves as the DocId and no mapping is necessary. Therefore, using integer full-text key values can help optimize full-text queries.

The Occurrence column contains an integer value. For each DocId value, there's a list of occurrence values that correspond to the relative word offsets of the particular keyword within that DocId. Occurrence values are useful in determining phrase or proximity matches, for example, phrases have numerically adjacent occurrence values. They're also useful in computing relevance scores; for example, the number of occurrences of a keyword in a DocId might be used in scoring.

The logical full-text index is usually split across multiple internal tables. Each internal table is called a full-text index fragment. Some of these fragments might contain newer data than others. For example, if a user updates the following row whose DocId is 3 and the table is auto change-tracked, a new fragment is created.

| DocumentID | Title |

|---|---|

3 |

Rear Reflector |

In the following example, which shows Fragment 2, the fragment contains newer data about DocId 3 compared to Fragment 1. Therefore, when the user queries for Rear Reflector the data from Fragment 2 is used for DocId 3. Each fragment is marked with a creation timestamp that can be queried by using the sys.fulltext_index_fragments catalog view.

Fragment 2

| Keyword | ColId | DocId | Occ |

|---|---|---|---|

Rear |

1 | 3 | 1 |

Reflector |

1 | 3 | 2 |

As can be seen from Fragment 2, full-text queries need to query each fragment internally and discard older entries. Therefore, too many full-text index fragments in the full-text index can lead to substantial degradation in query performance. To reduce the number of fragments, reorganize the fulltext catalog by using the REORGANIZE option of the ALTER FULLTEXT CATALOGTransact-SQL statement. This statement performs a master merge, which merges the fragments into a single larger fragment and removes all obsolete entries from the full-text index.

After being reorganized, the example index would contain the following rows:

| Keyword | ColId | DocId | Occ |

|---|---|---|---|

Crank |

1 | 1 | 1 |

Arm |

1 | 1 | 2 |

Tire |

1 | 1 | 4 |

Maintenance |

1 | 1 | 5 |

Front |

1 | 2 | 1 |

Rear |

1 | 3 | 1 |

Reflector |

1 | 2 | 2 |

Reflector |

1 | 2 | 5 |

Reflector |

1 | 3 | 2 |

Bracket |

1 | 2 | 3 |

Assembly |

1 | 2 | 6 |

3 |

1 | 2 | 7 |

| Full-text indexes | Regular SQL Server indexes |

|---|---|

| Only one full-text index allowed per table. | Several regular indexes allowed per table. |

| The addition of data to full-text indexes, called a population, can be requested through either a schedule or a specific request, or can occur automatically with the addition of new data. | Updated automatically when the data upon which they're based is inserted, updated, or deleted. |

| Grouped within the same database into one or more full-text catalogs. | Not grouped. |

Full-text search supports almost 50 diverse languages, such as English, Spanish, Chinese, Japanese, Arabic, Bangla, and Hindi. For a complete list of the supported full-text languages, see sys.fulltext_languages. Each of the columns contained in the full-text index is associated with a Microsoft Windows locale identifier (LCID) that equates to a language that is supported by full-text search. For example, LCID 1033 equates to U.S English, and LCID 2057 equates to British English. For each supported full-text language, SQL Server provides linguistic components that support indexing and querying full-text data that is stored in that language.

Language-specific components include the following items:

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Word breakers and stemmers | A word breaker finds word boundaries based on the lexical rules of a given language (word breaking). Each word breaker is associated with a stemmer that conjugates verbs for the same language. For more information, see Configure & manage word breakers & stemmers for search (SQL Server). |

| Stoplists | A system stoplist is provided, which contains a basic set of stopwords (also known as noise words). A stopword is a word that doesn't help the search and is ignored by full-text queries. For example, for the English locale words such as a, and, is, and the are considered stopwords. Typically, you need to configure one or more thesaurus files and stoplists. For more information, see Configure and Manage Stopwords and Stoplists for Full-Text Search. |

| Thesaurus files | SQL Server also installs a thesaurus file for each full-text language, and a global thesaurus file. The installed thesaurus files are empty, but you can edit them to define synonyms for a specific language or business scenario. By developing a thesaurus tailored to your full-text data, you can effectively broaden the scope of full-text queries on that data. For more information, see Configure and Manage Thesaurus Files for Full-Text Search. |

| Filters (iFilters) | Indexing a document in a varbinary(max), image, or xml data type column requires a filter to perform extra processing. The filter must be specific to the document type (.doc, .pdf, .xls, .xml, and so forth). For more information, see Configure and Manage Filters for Search. |

Word breakers (and stemmers) and filters run in the filter daemon host process (fdhost.exe).

Events

Mar 31, 11 PM - Apr 2, 11 PM

The biggest SQL, Fabric and Power BI learning event. March 31 – April 2. Use code FABINSIDER to save $400.

Register todayTraining

Module

Implement advanced search features in Azure AI Search - Training

Use more advanced features of Azure AI Search to improve your existing search solutions. Learn how to change the ranking on documents, boost the most important terms to your organization, and allow searching in multiple languages.