Events

Mar 31, 11 PM - Apr 2, 11 PM

The biggest SQL, Fabric and Power BI learning event. March 31 – April 2. Use code FABINSIDER to save $400.

Register todayThis browser is no longer supported.

Upgrade to Microsoft Edge to take advantage of the latest features, security updates, and technical support.

Applies to:

SQL Server

Azure SQL Database

Azure SQL Managed Instance

Azure Synapse Analytics

Analytics Platform System (PDW)

SQL database in Microsoft Fabric

Every SQL Server database has a transaction log that records all transactions and the database modifications that are made by each transaction. The transaction log is a critical component of the database and, if there's a system failure, the transaction log might be required to bring your database back to a consistent state. This guide provides information about the physical and logical architecture of the transaction log. Understanding the architecture can improve your effectiveness in managing transaction logs.

The SQL Server transaction log operates logically as if the transaction log is a string of log records. Each log record is identified by a log sequence number (LSN). Each new log record is written to the logical end of the log with an LSN that is higher than the LSN of the record before it. Log records are stored in a serial sequence as they're created, such that if LSN2 is greater than LSN1, the change described by the log record referred to by LSN2 occurred after the change described by the log record LSN1. Each log record contains the ID of the transaction that it belongs to. For each transaction, all log records associated with the transaction are individually linked in a chain using backward pointers that speed the rollback of the transaction.

The basic structure of an LSN is [VLF ID:Log Block ID:Log Record ID]. For more information, see the VLF and log block sections.

Here's an example of an LSN: 00000031:00000da0:0001, where 0x31 is the ID of the VLF, 0xda0 is the log block ID, and 0x1 is the first log record in that log block. For examples of LSNs, look at the output of sys.dm_db_log_info DMV and examine the vlf_create_lsn column.

Log records for data modifications record either the logical operation performed, or they record the before and after images of the modified data. The before image is a copy of the data before the operation is performed; the after image is a copy of the data after the operation has been performed.

The steps to recover an operation depend on the type of log record:

Logical operation logged

Before and after image logged

Many types of operations are recorded in the transaction log. These operations include:

The start and end of each transaction.

Every data modification (insert, update, or delete). Modifications include changes by system stored procedures or data definition language (DDL) statements to any table, including system tables.

Every extent and page allocation or deallocation.

Creating or dropping a table or index.

Rollback operations are also logged. Each transaction reserves space in the transaction log to make sure that enough log space exists to support a rollback that is caused by either an explicit rollback statement, or if an error is encountered. The amount of space reserved depends on the operations performed in the transaction, but generally it's equal to the amount of space used to log each operation. This reserved space is freed when the transaction is completed.

The section of the log file from the first log record that must be present for a successful database-wide rollback to the last-written log record is called the active part of the log, active log, or tail of the log. This is the section of the log required to a full recovery of the database. No part of the active log can ever be truncated. The log sequence number (LSN) of this first log record is known as the minimum recovery LSN (MinLSN). For more information on operations supported by the transaction log, see The transaction log.

Differential and log backups advance the restored database to a later time, which corresponds to a higher LSN.

The database transaction log maps over one or more physical files. Conceptually, the log file is a string of log records. Physically, the sequence of log records is stored efficiently in the set of physical files that implement the transaction log. There must be at least one log file for each database.

The SQL Server Database Engine divides each physical log file internally into several virtual log files (VLFs). Virtual log files have no fixed size, and there's no fixed number of virtual log files for a physical log file. The Database Engine chooses the size of the virtual log files dynamically while it's creating or extending log files. The Database Engine tries to maintain a few virtual files. The size of the virtual files after a log file has been extended is the sum of the size of the existing log and the size of the new file increment. The size or number of virtual log files can't be configured or set by administrators.

Virtual log file (VLF) creation follows this method:

If the log files grow to a large size in many small increments, they end up with many virtual log files. This can slow down database startup, log backup and restore operations, and cause transactional replication/CDC and Always On redo latency. Conversely, if the log files are set to a large size with few or just one increment, they contain few very large virtual log files. For more information on properly estimating the required size and autogrow setting of a transaction log, see the Recommendations section of Manage the size of the transaction log file.

We recommend that you create your log files close to the final size required, using the increments needed to achieve optimal VLF distribution, and have a relatively large growth_increment value.

See the following tips to determine the optimal VLF distribution for the current transaction log size:

SIZE argument of ALTER DATABASE is the initial size for the log file.FILEGROWTH argument of ALTER DATABASE sets, is the amount of space added to the file every time new space is required.For more information on FILEGROWTH and SIZE arguments of ALTER DATABASE, see ALTER DATABASE (Transact-SQL) File and Filegroup Options.

Tip

To determine the optimal VLF distribution for the current transaction log size of all databases in a given instance, and the required growth increments to achieve the required size, see this Fixing-VLFs script on GitHub.

During the initial stages of a database recovery process, SQL Server discovers all VLFs in all transaction log files, and builds a list of these VLFs. This process can take a long time depending on the number of VLFs present in the specific database. The more VLFs, the longer the process. A database can end up with large number of VLFs if frequent transaction log autogrowth or manual growth is encountered in small increments. When the number of VLFs reaches the range of several hundred thousand, you can encounter some or most of the following symptoms:

When you examine the SQL Server Error log, you might notice that a significant amount of time is spent before the analysis phase of the database recovery process. For example:

2022-05-08 14:42:38.65 spid22s Starting up database 'lot_of_vlfs'.

2022-05-08 14:46:04.76 spid22s Analysis of database 'lot_of_vlfs' (16) is 0% complete (approximately 0 seconds remain). Phase 1 of 3. This is an informational message only. No user action is required.

Additionally, SQL Server can log a MSSQLSERVER_9017 error when you restore a database that has a large number of VLFs:

Database %ls has more than %d virtual log files which is excessive. Too many virtual log files can cause long startup and backup times. Consider shrinking the log and using a different growth increment to reduce the number of virtual log files.

For more information, see MSSQLSERVER_9017.

To keep the total number of VLFs at a reasonable amount, such as a maximum of several thousand, you can reset the transaction log file to contain a smaller number of VLFs by performing the following steps:

Shrink the transaction log files manually.

Grow the files to the required size manually in one step using the following T-SQL script:

ALTER DATABASE <database name> MODIFY FILE (NAME='Logical file name of transaction log', SIZE = <required size>);

Note

This step is also possible in SQL Server Management Studio, using the database properties page.

After you set the new layout of the transaction log file with fewer VLFs, review and make necessary changes to the autogrow settings of the transaction log. This setting validation ensures that the log file avoids encountering the same problem in the future.

Before you perform any of these operations, make sure that you have a valid restorable backup in case you encounter issues later.

To determine the optimal VLF distribution for the current transaction log size of all databases in a given instance, and the required growth increments to achieve the required size, you can use the following GitHub script to fix VLFs.

Each VLF contains one or more log blocks. Each log block consists of the log records (aligned at a 4-byte boundary). A log block is variable in size and is always an integer multiple of 512 bytes (the minimum sector size SQL Server supports), with a maximum size of 60 KB. A log block is the basic unit of I/O for transaction logging.

In summary, a log block is a container of log records that's used as the basic unit of transaction logging when writing log records to disk.

Each log block within a VLF is uniquely addressed by its block offset. The first block always has a block offset that points past the first 8 KB in the VLF.

In general, a VLF is always filled up with log blocks. It's possible that the last log block in a VLF is empty (for example, doesn't contain any log records). This happens when a log record to be written doesn't fit into the current log block and also when the space left on the VLF is insufficient to hold this log record. In this case, an empty log block is created that fills up the VLF. The log record is inserted into the first block on the next VLF.

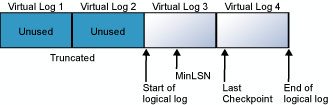

The transaction log is a wrap-around file. For example, consider a database with one physical log file divided into four VLFs. When the database is created, the logical log file begins at the start of the physical log file. New log records are added at the end of the logical log and expand toward the end of the physical log. Log truncation frees any virtual logs whose records all appear in front of the minimum recovery log sequence number (MinLSN). The MinLSN is the log sequence number of the oldest log record that is required for a successful database-wide rollback. The transaction log in the example database would look similar to the one in the following diagram.

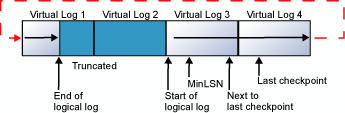

When the end of the logical log reaches the end of the physical log file, the new log records wrap around to the start of the physical log file.

This cycle repeats endlessly, as long as the end of the logical log never reaches the beginning of the logical log. If the old log records are truncated frequently enough to always leave sufficient room for all the new log records created through the next checkpoint, the log never fills. However, if the end of the logical log does reach the start of the logical log, one of two things occurs:

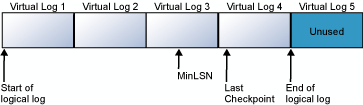

If the FILEGROWTH setting is enabled for the log and space is available on the disk, the file is extended by the amount specified in the growth_increment parameter, and the new log records are added to the extension. For more information about the FILEGROWTH setting, see ALTER DATABASE (Transact-SQL) File and Filegroup Options.

If the FILEGROWTH setting isn't enabled, or the disk that is holding the log file has less free space than the amount specified in growth_increment, a 9002 error is generated. For more information, see Troubleshoot a full transaction log (SQL Server Error 9002).

If the log contains multiple physical log files, the logical log moves through all the physical log files before it wraps back to the start of the first physical log file.

Important

For more information about transaction log size management, see Manage the size of the transaction log file.

Log truncation is essential to keep the log from filling. Log truncation deletes inactive virtual log files from the logical transaction log of a SQL Server database, freeing space in the logical log for reuse by the physical transaction log. If a transaction log is never truncated, it will eventually fill all the disk space that is allocated to its physical log files. However, before the log can be truncated, a checkpoint operation must occur. A checkpoint writes the current in-memory modified pages (known as dirty pages) and transaction log information from memory to disk. When the checkpoint is performed, the inactive portion of the transaction log is marked as reusable. Thereafter, a log truncation can free the inactive portion. For more information about checkpoints, see Database checkpoints (SQL Server).

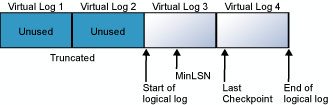

The following diagrams show a transaction log before and after truncation. The first diagram shows a transaction log that has never been truncated. Currently, four virtual log files are in use by the logical log. The logical log starts at the front of the first virtual log file and ends at virtual log 4. The MinLSN record is in virtual log 3. Virtual log 1 and virtual log 2 contain only inactive log records. These records can be truncated. Virtual log 5 is still unused and isn't part of the current logical log.

The second diagram shows how the log appears after being truncated. Virtual log 1 and virtual log 2 have been freed for reuse. The logical log now starts at the beginning of virtual log 3. Virtual log 5 is still unused, and it isn't part of the current logical log.

Log truncation occurs automatically after the following events, except when delayed for some reason:

Log truncation can be delayed by various factors. In the event of a long delay in log truncation, the transaction log can fill up. For information, see Factors that can delay log truncation and Troubleshoot a full transaction log (SQL Server Error 9002).

This section describes the role of the write-ahead transaction log in recording data modifications to disk. SQL Server uses a write-ahead logging (WAL) algorithm, which guarantees that no data modifications are written to disk before the associated log record is written to disk. This maintains the ACID properties for a transaction.

For more information about WAL, see SQL Server I/O fundamentals.

To understand how write-ahead logging works in relation to the transaction log, it's important for you to know how modified data is written to disk. SQL Server maintains a buffer cache (also called a buffer pool) into which it reads data pages when data must be retrieved. When a page is modified in the buffer cache, it isn't immediately written back to disk; instead, the page is marked as dirty. A data page can have more than one logical write made before it's physically written to disk. For each logical write, a transaction log record is inserted in the log cache that records the modification. The log records must be written to disk before the associated dirty page is removed from the buffer cache and written to disk. The checkpoint process periodically scans the buffer cache for buffers with pages from a specified database and writes all dirty pages to disk. Checkpoints save time during a later recovery by creating a point at which all dirty pages are guaranteed to have been written to disk.

Writing a modified data page from the buffer cache to disk is called flushing the page. SQL Server has logic that prevents a dirty page from being flushed before the associated log record is written. Log records are written to disk when the log buffers are flushed. This happens whenever a transaction commits or the log buffers become full.

This section presents concepts about how to back up and restore (apply) transaction logs. Under the full and bulk-logged recovery models, taking routine backups of transaction logs (log backups) is necessary for recovering data. You can back up the log while any full backup is running. For more information about recovery models, see Back Up and Restore of SQL Server Databases.

Before you can create the first log backup, you must create a full backup, such as a database backup or the first in a set of file backups. Restoring a database by using only file backups can become complex. Therefore, we recommend that you start with a full database backup when you can. Thereafter, backing up the transaction log regularly is necessary. This not only minimizes work-loss exposure but also enables truncation of the transaction log. Typically, the transaction log is truncated after every conventional log backup.

Important

We recommend taking frequent enough log backups to support your business requirements, specifically your tolerance for work loss such as might be caused by a damaged log storage.

The appropriate frequency for taking log backups depends on your tolerance for work-loss exposure balanced by how many log backups you can store, manage, and, potentially, restore. Think about the required recovery time objective (RTO) and recovery point objective (RPO) when implementing your recovery strategy, and specifically the log backup cadence. Taking a log backup every 15 to 30 minutes might be enough. If your business requires that you minimize work-loss exposure, consider taking log backups more frequently. More frequent log backups have the added advantage of increasing the frequency of log truncation, resulting in smaller log files.

To limit the number of log backups that you need to restore, it's essential to routinely back up your data. For example, you might schedule a weekly full database backup and daily differential database backups.

Think about the required RTO and RPO when implementing your recovery strategy, and specifically the full and differential database backup cadence.

For more information about transaction log backups, see Transaction log backups (SQL Server).

A continuous sequence of log backups is called a log chain. A log chain starts with a full backup of the database. Usually, a new log chain is only started when the database is backed up for the first time, or after the recovery model is switched from simple recovery to full or bulk-logged recovery. Unless you choose to overwrite existing backup sets when creating a full database backup, the existing log chain remains intact. With the log chain intact, you can restore your database from any full database backup in the media set, followed by all subsequent log backups up through your recovery point. The recovery point could be the end of the last log backup or a specific recovery point in any of the log backups. For more information, see Transaction log backups (SQL Server).

To restore a database up to the point of failure, the log chain must be intact. That is, an unbroken sequence of transaction log backups must extend up to the point of failure. Where this sequence of log must start depends on the type of data backups you're restoring: database, partial, or file. For a database or partial backup, the sequence of log backups must extend from the end of a database or partial backup. For a set of file backups, the sequence of log backups must extend from the start of a full set of file backups. For more information, see Apply Transaction Log Backups (SQL Server).

Restoring a log backup rolls forward the changes that were recorded in the transaction log to recreate the exact state of the database at the time the log backup operation started. When you restore a database, you'll have to restore the log backups that were created after the full database backup that you restore, or from the start of the first file backup that you restore. Typically, after you restore the most recent data or differential backup, you must restore a series of log backups until you reach your recovery point. Then, you recover the database. This rolls back all transactions that were incomplete when the recovery started and brings the database online. After the database has been recovered, you can't restore any more backups. For more information, see Apply Transaction Log Backups (SQL Server).

Checkpoints flush dirty data pages from the buffer cache of the current database to disk. This minimizes the active portion of the log that must be processed during a full recovery of a database. During a full recovery, the following types of actions are performed:

A checkpoint performs the following processes in the database:

Writes a record to the log file, marking the start of the checkpoint.

Stores information recorded for the checkpoint in a chain of checkpoint log records.

One piece of information recorded in the checkpoint is the log sequence number (LSN) of the first log record that must be present for a successful database-wide rollback. This LSN is called the Minimum Recovery LSN (MinLSN). The MinLSN is the minimum of the:

The checkpoint records also contain a list of all the active transactions that have modified the database.

If the database uses the simple recovery model, marks for reuse the space that precedes the MinLSN.

Writes all dirty log and data pages to disk.

Writes a record marking the end of the checkpoint to the log file.

Writes the LSN of the start of this chain to the database boot page.

Checkpoints occur in the following situations:

The SQL Server Database Engine generates automatic checkpoints. The interval between automatic checkpoints is based on the amount of log space used and the time elapsed since the last checkpoint. The time interval between automatic checkpoints can be highly variable and long, if few modifications are made in the database. Automatic checkpoints can also occur frequently if lots of data is modified.

Use the recovery interval server configuration option to calculate the interval between automatic checkpoints for all the databases on a server instance. This option specifies the maximum time the Database Engine should use to recover a database during a system restart. The Database Engine estimates how many log records it can process in the recovery interval during a recovery operation.

The interval between automatic checkpoints also depends on the recovery model:

If the database is using either the full or bulk-logged recovery model, an automatic checkpoint is generated whenever the number of log records reaches the number the Database Engine estimates it can process during the time specified in the recovery interval option.

If the database is using the simple recovery model, an automatic checkpoint is generated whenever the number of log records reaches the lesser of these two values:

For information about setting the recovery interval, see Configure the recovery interval (min) (server configuration option).

Tip

The -k SQL Server advanced setup option enables a database administrator to throttle checkpoint I/O behavior based on the throughput of the I/O subsystem for some types of checkpoints. The -k setup option applies to automatic checkpoints and any otherwise unthrottled checkpoints.

Automatic checkpoints truncate the unused section of the transaction log if the database is using the simple recovery model. However, if the database is using the full or bulk-logged recovery models, the log isn't truncated by automatic checkpoints. For more information, see The transaction log.

The CHECKPOINT statement now provides an optional checkpoint_duration argument that specifies the requested period of time, in seconds, for checkpoints to finish. For more information, see CHECKPOINT.

The section of the log file from the MinLSN to the last-written log record is called the active portion of the log, or the active log. This is the section of the log required to do a full recovery of the database. No part of the active log can ever be truncated. All log records must be truncated from the parts of the log before the MinLSN.

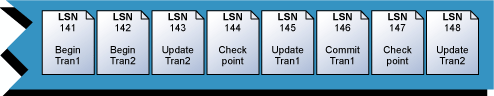

The following diagram shows a simplified version of the end-of-a-transaction log with two active transactions. Checkpoint records have been compacted to a single record.

LSN 148 is the last record in the transaction log. At the time that the recorded checkpoint at LSN 147 was processed, Tran 1 had been committed and Tran 2 was the only active transaction. That makes the first log record for Tran 2 the oldest log record for a transaction active at the time of the last checkpoint. This makes LSN 142, the Begin transaction record for Tran 2, the MinLSN.

The active log must include every part of all uncommitted transactions. An application that starts a transaction and doesn't commit it or roll it back prevents the Database Engine from advancing the MinLSN. This situation can cause two types of problems:

Recovery of long-running transactions, and the problems described in this article, can be avoided by using Accelerated database recovery, a feature available starting with SQL Server 2019 (15.x) and in Azure SQL Database.

The Log Reader Agent monitors the transaction log of each database configured for transactional replication, and it copies the transactions marked for replication from the transaction log into the distribution database. The active log must contain all transactions that are marked for replication, but that haven't yet been delivered to the distribution database. If these transactions aren't replicated in a timely manner, they can prevent the truncation of the log. For more information, see Transactional Replication.

Events

Mar 31, 11 PM - Apr 2, 11 PM

The biggest SQL, Fabric and Power BI learning event. March 31 – April 2. Use code FABINSIDER to save $400.

Register todayTraining

Module

Understand write-ahead logging - Training

Azure Database for PostgreSQL is an ACID compliant database service. Write-ahead logging ensures changes are both atomic and durable (the A and D in ACID). Changes are first written to the log before they're committed to the database. In this module, you learn how Azure Database for PostgreSQL implements write-ahead logging, and how the log can be used for replication and logical decoding.

Documentation

The transaction log - SQL Server

Learn about the transaction log. Every SQL Server database records all transactions and database modifications that you need if there's a system failure.

sys.dm_db_log_info (Transact-SQL) - SQL Server

The sys.dm_db_log_info (Transact-SQL) dynamic management function returns virtual log file (VLF) information from the transaction log.

Database Checkpoints (SQL Server) - SQL Server

Learn about checkpoints, known good points from which the SQL Server Database Engine can start applying changes contained in the log during recovery.